István Turcsányi, MD1, Andreas Gohritz, MD2,3 and Jan Fridén, MD, PhD2,4

From the 1Department of Orthopaedics, Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg County Hospitals and University Hospital, Nyíregyháza, Hungary, 2Swiss Paraplegic Centre, Nottwil, 3Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Hand Surgery, University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland and 4Centre for Advanced Reconstruction of Extremities (CARE) and Department of Hand Surgery, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, Sweden.

All authors contributed equally to this work.

OBJECTIVE: Surgical restoration of upper extremity function in tetraplegia is acknowledged as beneficial, yet in many countries it is underused or absent. This study describes a 10-year review of a project to implement a tetraplegia upper extremity surgery service in Hungary. The main aims were to increase awareness among patients, the medical community and the public about the benefits of this rehabilitation. The process of implementing a national tetraplegia hand surgery service is described, together with a retrospective outcome study of upper extremity function after surgical reconstruction in this service.

METHODS: A total of 141 tetraplegic patients were assessed. Of these, 57 (40%) underwent a total of 126 reconstructions, including 366 procedures, between 2002 and 2012. Clinical parameters and patient-perceived results demonstrated improved functions and abilities. Considerable media attention and scientific presentations facilitated making this service permanent. In 2009, surgical rehabilitation in tetraplegia became a recognized part of the rehabilitation protocol in Hungary.

RESULTS: These results suggest that the success of starting a national tetraplegia hand service relies on convincing postoperative outcomes, patient-to-patient contacts, and co- operation between rehabilitation specialists, therapists, health authorities and surgeons.

Discussion: The leadership of dedicated hand surgeons is necessary to provide and disseminate scientific support for the concept of tetraplegia hand surgery and to stimulate interdisciplinary communication and educational programmes.

Key words: tetraplegia; hand surgery; national service; rehabilitation; reconstruction.

J Rehabil Med 2016; 48: 571–575

Correspondence address: Jan Fridén, Centre for Advanced Reconstruction of Extremities (CARE) and Department of Hand Surgery, Building U1, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, SE-431 80 Mölndal, Sweden. E-mail: jan.friden@orthop.gu.se

Accepted April 5, 2016; Epub ahead of print Jun 20, 2016

INTRODUCTION

Spinal cord injury is, at present, incurable; thus, for tetraplegic patients, arm and hand usability remains the foremost resource other than the brain in pursuit of a self-determined life (1). Reconstructive surgery of the upper extremities using tendon transfer and joint stabilizations or, more recently, nerve transfer, has become an accepted part of rehabilitation of patients with cervical spinal cord injury (2, 3). Numerous case series have demonstrated that key functions, such as elbow extension and handgrip can be restored reliably in individuals affected by traumatic or non-traumatic tetraplegia (4–11). Consequently, the mobility, spontaneity and independence of tetraplegic individuals can be markedly and persistently increased (12–14). Snoek et al. (15) reported that 77% of 565 tetraplegic patients expected to experience important or very important improvements in their quality of life if their hand function was improved. However, in many countries tetraplegia upper extremity surgery is rarely performed. For example, in the USA less than 7% of patients eligible for surgical reconstruction actually undergo these procedures (16). Multiple barriers can hinder the awareness of such upper extremity interventions, including a shortage of hand surgeons with sufficient experience, lack of information about these procedures, scepticism within patient and non-surgical communities towards surgical rehabilitation, weak interdisciplinary relationships and insufficient financial and/or social support for tetraplegic patients (16–19).

The aim of this paper is to describe the implementation of a new specialized hand surgery service for patients with tetraplegia in Hungary starting in 2002 and its evolution until the present day.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The process of establishing a national tetraplegia hand surgery service is described (Table I, Fig. 1), including a retrospective outcome study of upper extremity function after surgical reconstruction by this service (Tables II and III). The latter comprised strength measurements of elbow extension, key pinch and grip, measurement of opening of the hand and patient-perceived outcomes according to House (7).

|

Table I. Steps involved in launching a new national tetraplegia hand surgery service |

|||

|

Phases |

Recommended steps |

Comments |

Experience of Hungarian project |

|

Preparation |

Collect information |

Communicate with experts |

2001: Participation at 7th International Conference on Tetraplegia: Surgery and Rehabilitation, Bologna, Italy |

|

Increase awareness |

Offer assessments to patients in rehabilitation units. Describe benefits |

2001: Doubt and conservatism initially. Only sporadic patients referred for assessment. Authorities informed about pilot project |

|

|

Decision to start |

Build dedicated team early in the process |

2002: Hand surgeon, ergotherapist, physiotherapist, anaesthesiologist, rehabilitation medicine physician engaged in project |

|

|

Initiation |

Offer reconstruction to first patients |

Based on favourable examination and patient motivation Support of experienced tetraplegia hand surgeon |

2002: Reconstruction and rehabilitation with successful result in patient grouped ICHFT 5 (Tr +) 2002: 3 initial reconstructions with support of experienced tetraplegia hand surgeon |

|

Present service plan |

Address to local health authorities |

2002: Process and necessary infrastructure adaptations outlined. Approval received by hospital director and city authorities |

|

|

Recruiting more candidates for assessment and possible surgery |

Expand exposure. Send out invitations to tetraplegic persons |

Creation of web-page to promote contact between patients 2002: Presentation of first case on national rehabilitation congress 2003: Lecture at national rehabilitation congress |

|

|

Consolidation |

Start larger operative series based on good initial results |

Secure expertise and infrastructure for surgery and rehabilitation |

2002–2003: Examination and operation of 14 patients within one year |

|

Present results on scientific meetings |

Submit papers to scientific meetings of multiple disciplines |

2004–2012: 7 invited international lectures on tetraplegia surgery, various national papers |

|

|

Contact with media |

Invite news and medical media. Interview patients |

2002–2004: Multiple local and national TV channel appearances |

|

|

Development |

Scientific study design, data collection and reports |

Involve and inspire undergraduate and graduate students to participate |

2004–2006: 2-centre study of triceps reconstruction mechanics. Clinical outcomes studies |

|

Scientific collaboration |

Identify national/international academic partners |

2007–2008: Visits by first author to several established tetraplegia hand surgery units in Europe and the USA |

|

|

Succession |

Knowledge transfer and expertise succession |

Secure succession and continuity by training younger colleagues of different ages |

2009–2015: 8 international courses on “Tendon Transfer in Tetraplegia”, organized in Budapest, Nyíregyháza, Tarcal/Hungary and Nottwil, Switzerland, overall 180 participants from 28 countries 2014: Visit to Hand Trauma Center, Trzebnica, Poland to launch new tetraplegia hand surgery service with former participants of tetraplegia hand surgery course (6 initial operations) |

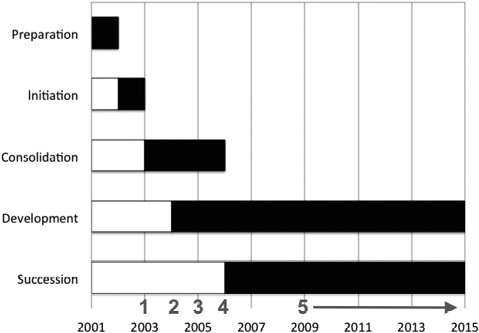

Fig. 1. Key elements of launching and establishing a comprehensive upper extremity surgical service in tetraplegia. Multiple milestones (numbers in red) were identified during this process: 1: Securing designated beds and rehabilitation resources at regional hospital (2003). 2: Creating governing guidelines, protocols and algorithms (2004). 3: Establishing a reliable referral pattern nationally (2005). 4: Securing official status as a national unit (2006). 5: Providing continuous medical education available to surgeons and therapists (2009–2015).

Initial phase

In an attempt to create a tetraplegia upper extremity surgery service in Hungary, the authors decided to launch a project in 2001, inspired by the 7th International Conference on Surgical Rehabilitation of the Tetraplegic Upper Extremity in Bologna, Italy. The aim was to increase awareness of this therapeutic option in patients, colleagues in rehabilitation medicine, neurosurgery and orthopaedic surgery, therapists, health administration and the public.

Our first patient, a 27-year-old tetraplegic woman, presented to us in February 2002. She was categorized as OCu5(Tr+) according to the International Classification of Hand Function in Tetraplegia (ICHFT, Table II). In April 2002, a standard procedure at that time was performed on her right (dominant) hand (i.e. brachioradialis to flexor pollicis longus and extensor carpi radialis longus to flexor digitorum profundus tendon transfer together with split distal flexor pollicis longus tenodesis of the thumb interphalangeal joint and Zancolli lasso plasty) (9, 20). Following this successful surgical reconstruction, a structured project plan (roughly as described in Fig. 1) was presented to the local hospital director and city authorities. The project was initiated with their support. A large number of tetraplegic patients were invited to undergo assessment, and suitable patients were offered reconstructive upper extremity surgery. Within one year, 14 tetraplegic patients classified as OCu3–5 received surgical reconstructions. All patients considered the surgical result beneficial and recommended other tetraplegic patients to undergo assessment for the same procedures.

|

Table II. International Classification of Surgery of the Hand in Tetraplegia |

|||

|

Group |

Spinal cord segment |

Possible muscle transfers |

Number of extremities operated |

|

0 |

≥ C5 |

No transferable muscle below elbow |

0 |

|

1 |

C5 |

Brachioradialis (BR) |

8 |

|

2 |

C6 |

+ Extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) |

11 |

|

3 |

C6 |

+ Extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) |

15 |

|

4 |

C6 |

+ Pronator teres (PT) |

24 |

|

5 |

C7 |

+ Flexor carpi radialis (FCR) |

12 |

|

6 |

C7 |

+ Extensor digitorum |

4 |

|

7 |

C7 |

+ Extensor pollicis longus |

1 |

|

8 |

C8 |

+ Flexor digitorum |

2 |

|

9 |

C8 |

No intrinsic hand muscles |

0 |

|

10 (X) |

|

Exceptions |

3 |

|

Additional classification includes sensation and triceps function: O: ocular control; Cu: afferent sensory cutaneous control; 2-point discrimination ≤ 10 mm in thumb, Tr –/+: triceps strength grade 4 (muscle strength 0–5 according to Medical Research Council classification) absent/present. |

|||

Increasing awareness and building networks

These initial results were presented in 2003 at 2 national meetings and 1 international congress. A website was created to promote contact between operated patients and potential candidates. It was maintained by a tetraplegic patient who had himself benefitted from reconstruction. Examinations and operations were initially coordinated by the hand surgeon. Information for potential candidates and the public was provided by the hand surgeon, satisfied patients, the hospital’s communication department and multiple media reports. A network of interested neuro-rehabilitation experts, physiotherapists and ergotherapists was established in 2004. Initially the network included 2 rehabilitation doctors, 2 hand surgeons, 2 ergotherapists, 2 physiotherapists, 1 anaesthesiologist with subspecialty in pain medicine, and 1 medical engineer working in 2 separate units and with the National Rehabilitation Centre in Budapest as the main referral unit. Acceptance of surgical rehabilitation of the paralysed upper extremity increased due to the marked objective and subjective functional gains of the operated individuals. The first author was invited to be consultant at the Hungarian National Rehabilitation Centre in 2006, and hand surgery became a recognized part of the treatment protocol in tetraplegia. The first European Tetraplegia Hand Surgery Course was given in Budapest, Hungary in March 2009.

Results of functional surgery

Both objective measurements and patient-reported outcomes according to House demonstrated substantial functional gains after surgery.

Objective outcomes

Overall, 141 tetraplegic patients were examined. Of these, 57 patients (10 females, 47 males) were treated with 126 surgical reconstructions, including 366 procedures, on 80 upper extremities (i.e. 23 bilaterally) between 2002 and 2012. Mean age at injury was 29.2 years (age range 17–56 years). The mean interval between injury and operation was 5.4 years (standard deviation 5.9) (range 1–27 years), but outcomes were not related to the delay from injury to time of surgical reconstruction. All patients sustained traumatic spinal cord injuries from level C4 to C7 and were classified as OCu1–9 and with (n = 50 arms) or without (n = 30 arms) functioning triceps according to the ICHFT (Table II). Surgical treatment included restoration of elbow extension (n = 50), active key pinch and grasp (n = 76). Elbow extension, key pinch and grip strengths were markedly improved (Table III).

|

Table III. Performed surgical procedures to achieve patients’ ability goals |

||||

|

Ability goal |

Functional goal |

Procedure |

Procedures n |

Postoperative outcomes Mean (SD) |

|

Stabilizing elbow in space, reaching overhead objects, pushing wheelchair, stabilizing trunk |

Elbow extension |

Reconstruction of triceps function Posterior deltoid-triceps |

50 |

Elbow extension strength 3.8 (MRC) (0.6) |

|

Manipulation of instruments, handwriting, pushing wheelchair, communication (hand shake, mobile phone, keyboard) |

Grip |

Reconstruction of grip Passive key grip BR-ECRB FPL-distal radius tenodesis Active key grip BR-FPL Grasp (global finger flexion) ECRL-FDP BR-FDP |

3 17

45

41 17 |

0.7 kg (0.6) 2.3 kg (1.5)

2.5 kg (1.7)

6.2 kg (1.6) 3.3 kg (1.3) |

|

Reaching for, e. g. cup or glass, positioning of thumb and fingers for improved grasp control (coming around object) |

Opening of the hand |

Reconstruction of thumb and finger extension Passive opening EPL-dorsal forearm fascia tenodesis Active opening PT-EDC and EPL/APL BR-EDC Correction of intrinsic tightness Ulnar wing resection |

35

5 1 1 |

6.0 cm (1.6)

6.0 cm (1.1)

|

|

|

|

Thumb stabilization Split FPL-EPL tenodesis (thumb IP joint) combined with CMC 1 arthrodesis |

66

|

|

|

|

|

Reconstruction of intrinsics Zancolli-Lasso tenodesis House tenodesis EDM-APB |

24 29 9 |

|

|

|

Wrist alignment |

Prevention of radial deviation during wrist extension ECU tenodesis |

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

366 |

|

|

APB: abductor pollicis brevis; APL: abductor pollicis longus; BR: brachioradialis; CMC: carpometacarpal; ECRB: extensor carpi radialis brevis; ECRL: extensor carpi radialis longus; EDC: extensor digitorum communis; ECU: extensor carpi ulnaris; EDM: extensor digiti minimi; EPL: extensor pollicis longus; FDP: flexor digitorum profundus, FPL: flexor pollicis longus; IP: interphalangeal, PT: pronator teres; SD: standard deviation. Opening was defined as maximal thumb to index distance. Rehabilitation typically includes active training within 24 h post-surgery and orthosis during night and between training sessions. |

||||

The complication rate was less than 4%, and included haematoma (n = 2), wound infection (n = 2) and elbow extension deficit of 30° (n = 1).

Patient perceived outcomes

The majority of patients reported improvements in important daily activities after surgery. No patient was worse after surgery. Seventy-four percent of patients reported improvements in 1 or several of the following items: washing, brushing teeth, using utensils, dressing upper extremity, writing, wheelchair propulsion, handling small objects and opening doors. No or limited changes were reported for: dressing lower extremity, transfer to and from the car, couch, toilet and bed, and several activities that required either good shoulder muscle strength or fine motor control.

DISCUSSION

Although reconstructive upper extremity surgery in tetraplegia has been reported as highly beneficial, it is profoundly underused or not accessible even in highly developed countries (16). Starting a new national service seems a logical step, but may face numerous obstructions before being realized.

In accordance with the literature, typical barriers included scepticism regarding surgical rehabilitation from the patients, physiatrists and therapists, due to weak interdisciplinary exchange and lack of information provision to patients (17. 18). Other potential factors that may affect the start of such a service are insufficient social support for patients, questionable motivation, negative attitudes, incomplete insurance coverage or inability to accommodate tetraplegic patients (19). The crucial point was to gain the rehabilitation experts’ trust and support. Failing this initially, another option was to directly approach patients and to offer assessment as well as inform them about surgery and, in selected cases, carry out successful operations. The support of an experienced tetraplegia hand surgeon was necessary to avoid unsuccessful cases and to follow the basic rule of nil nocere (“do no harm”). Our results compared favourably with other case series (6).

Patients played a key role in the decision-making process, including the assessment of risks and benefits of upper extremity surgery. We judged it important to perform a large number of successful operations in a relatively short period of time (14 patients within the first year), create a website for patients, arrange meetings between the operated and non-operated patients, present the results at conferences, arrange lectures for doctors interested in tetraplegia rehabilitation, publish scientific articles in the field of tetraplegia hand surgery and rehabilitation and invite media. It is commonly commented that this type of medical service requires a high level of resources because of the labour-intensive and long-term care and rehabilitation needed postoperatively. While most of the caregivers agreed that this medically and socially vulnerable patient population should have access to the best treatment and care available, the infrastructural platform was a topic for disagreement and debate. In our opinion, the implementation of this type of highly specialized care should be directed and controlled by national health authorities. In retrospect, we probably would have avoided some of the above-mentioned obstacles by instituting an executive working group of experts and patients at an early stage. This would have taken into account the interests of all involved parties, governed by an independent authority and with a clear timetable to identify the “if?”, “what?” and “when?” issues. Thereafter, a strong patient perspective, together with the professional aspects, should identify the “how?” and “where?”. To avoid narrow-minded and prestige-related arguments, the patient perspective should, again, have a powerful role in the final decision. Once the decision is made, all positive forces should be aimed at making this service as successful as possible from as many aspects as possible, such as quality, patient security, accessibility, teaching and development, including continuous education. Regular site visits and outcome controls by health authorities may help to maintain the predefined standards. Since the spinal cord injured patients represent a population with special needs and care throughout life, it is recommended to establish the tetraplegia hand surgery service within, or in close proximity to, a comprehensive spinal unit.

The aim of starting a tetraplegia upper extremity surgery service in Hungary could finally be realized despite initial difficulties. Other countries may face the same problems. The collaboration of rehabilitation medicine doctors, surgeons and therapists is instrumental for success. Failing this would make the service difficult to maintain over time, especially considering the need for expeditious actions; for example, when nerve transfer surgery is indicated and should be undertaken within a relatively short time window of approximately one year after injury (2, 21–22). Reconstructive surgery should probably be started with patients from ICHFT groups 4–5, as their very low functional level can be dramatically enhanced by time-proven procedures with predictable results. However, with time, the level of sophistication of surgical expertise will expand and allow for more advanced, but yet much-needed, surgical reconstruction, such as nerve transfer combined with tendon transfers.

This review of a model process demonstrates that the implementation of a national tetraplegia hand surgery requires a target-orientated perspective and optimism, endurance, communication and time, but may be highly rewarding for both patients and caregivers and serve as a guideline for similar projects in other countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Professor Antal Renner for his thoughtful and motivating support throughout this project.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES