Kirstine Amris, MD1, Eva Ejlersen Wæhrens, MSc, PhD, OT1,2, Anders Stockmarr, MSc, PhD1,3, Henning Bliddal, MD, DMSc1 and Bente Danneskiold-Samsøe, MD, DMSc1

From the 1The Parker Institute, Department of Rheumatology, Copenhagen University Hospital Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg, Frederiksberg, 2Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, 3Department of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the relationships between key outcome variables, classified according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), and observed and self-reported functional ability in patients with chronic widespread pain.

DESIGN: Cross-sectional with systematic data collection in a clinical setting.

SUBJECTS: A total of 257 consecutively enrolled women with chronic widespread pain.

METHODS: Multidimensional assessment using self-report and observation-based assessment tools identified to cover ICF categories included in the brief ICF Core Set for chronic widespread pain.

RESULTS: Relationships between ICF variables and observed functional ability measured with the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) were few. Out of 36 relationships analysed, only 4 ICF variables showed a moderate correlation with the AMPS motor ability measure. A moderate to strong correlation between numerous ICF variables and self-reported functioning was noted. Multivariate regression modelling supported significant contributions from pain and psychosocial variables to the variability in self-reported functional ability, but not to the variability in AMPS ability measures.

CONCLUSION: Observation-based assessment of functional ability in patients with chronic widespread pain is less influenced by pain and psychosocial factors than are self-reported evaluations. Valid observation-based assessment tools, such as the AMPS, should be included in clinical evaluation and future research addressing functional outcomes in this patient population.

Key words: fibromyalgia; CWP; ADL ability; ICF; AMPS.

J Rehabil Med 2014; 46: 00–00

Correspondence address: Kirstine Amris, The Parker Institute, Frederiksberg Hospital, Nordre Fasanvej 57, DK-2000 Frederiksberg, Denmark. E-mail: kirstine.amris@regionh.dk

Accepted May 22, 2014; Epub ahead of print Aug 6, 2014

This article has been fully handled by one of the Associate Editors, who made the decision for acceptance, as it originates from the institute where the Editor-in-Chief is active.

Introduction

The overall aim of rehabilitation is to enable individuals with disabilities to achieve and maintain the best possible functioning in their environment (1). Chronic widespread pain (CWP) carries a high level of disease burden, including disability affecting activities of daily living and health-related quality of life (2). Functioning is also considered a core outcome domain in clinical pain research (3–5). Pain interference with functional ability is, however, complex; research suggests a significant heterogeneity and differences in, for example, adaptation to pain across different subgroups of patients with chronic pain (6), which may influence functional outcome. Furthermore, there are different conceptualizations of the term functioning, and no consensus on which assessment tools to use. In most studies addressing patients with CWP, questionnaire-based self-reporting of functional ability or performance-based evaluations, assessing body functions (e.g. muscle strength) or aspects of mobility (e.g. walking ability), appear to be the gold standard (7).

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (8) offers a framework for structuring determinants of disability. Attempts to develop standardized ICF Core Sets have been made for a number of musculoskeletal pain disorders (9), including the definition of ICF Core Sets for CWP (3). Initiatives to validate the ICF Core Set for CWP based on statistical models (10, 11), and from the patient perspective using focus group methodology (12) as well as content comparison with frequently applied assessment instruments, have been reported (13, 14).

We have previously reported significant functional disability in women with CWP, based on standardized, observation-based assessment of the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL), and a low level of agreement between self-reported and observed ADL ability in this patient population (15). The design of this previous study included a comprehensive baseline assessment using instruments identified to cover ICF categories included in the brief ICF Core Set for CWP (3).

Based on these data, the objective of the current study was to evaluate the relationship between measures of observed functional ability, specified as ADL motor and ADL process ability, using the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS), and key outcome variables included in the ICF measurement framework. A further objective was to evaluate whether relationships between ICF variables and measures of observed functional ability differed from those obtained for self-reported functional ability on the physical function subscale of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ function) (16) and the physical functioning subscale of the Short-Form 36 (SF-36 physical functioning) (17, 18).

Methods

Study design and setting

The study was cross-sectional with systematic data collection in a clinical setting. Data were obtained on female patients diagnosed with CWP and consecutively referred for rehabilitation at the Department of Rheumatology, Frederiksberg Hospital. A comprehensive baseline assessment based on the brief ICF Core Set for CWP (3) was performed on all patients before enrolment in the rehabilitation programme. Several self-report and observation-based assessment tools were applied in the data collection and the data were stored in a clinical database. Data were collected from 1 March 2007 to 28 February 2009 and all examination methods were approved by the local ethics committee (KF 01-045/03).

Participants

The referral diagnosis of CWP was based on the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) definition of widespread pain (i.e. pain axially and in minimum 3 body quadrants) (19). The diagnostic assessment prior to referral included a full rheumatologic examination and extensive blood test screening on all patients. Exclusion criteria for enrolment in the rehabilitation programme were severe physical impairment necessitating assistance in personal activities of daily living (PADL), concurrent history of major psychiatric disorder not related to the pain disorder, and other medical conditions capable of causing patients’ symptoms (e.g. uncontrolled inflammatory/autoimmune disorder, uncontrolled endocrine disorder, malignancy, etc.).

Data sources and measurements

The brief ICF Core Set for CWP and applied instruments identified to cover ICF categories included in the brief ICF Core Set for CWP are presented in Table I. Several information sources and instruments were applied, some of these covering the same ICF category. However, a few ICF categories encompassed in the brief ICF Core Set for CWP were not covered by the applied instruments, in particular categories related to interpersonal relations.

|

Table I. Instruments classified according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Sets for chronic widespread pain (CWP) (3) |

|

|

ICF Core Sets for CWP |

Instruments in this study |

|

Body functions |

|

|

Emotional functions |

GAD-10, MDI, SF-36, FIQ |

|

Sensation of pain |

FIQ, SF-36, GAD-10, CPA |

|

Exercise tolerance functions |

Mob-T |

|

Psychomotor functions |

FIQ, SF-36 |

|

Control of voluntary movement functions |

AMPS motor |

|

Energy and drive functions |

Mob-T, SF-36, FIQ, MDI |

|

Sleep functions |

FIQ, MDI |

|

Content of thoughts |

CSQ, MDI, GAD-10 |

|

Muscle power functions |

Grippit, LIDO Multi Joint |

|

Attention function |

GAD-10, MDI |

|

Activity and participation |

|

|

Carrying out daily routines |

AMPS, SF-36 |

|

Handling stress and other psychological demands |

CSQ, GAD-10 |

|

Family relationships |

SF-36 |

|

Remunerative employment |

FIQ, SF-36, BIQ |

|

Intimate relationships |

|

|

Walking |

6MWT, SF-36, FIQ |

|

Recreation and leisure |

SF-36 |

|

Solving problems |

AMPS process, CSQ |

|

Lifting and carrying objects |

AMPS motor, SF-36 |

|

Doing housework |

AMPS, FIQ, SF-36 |

|

Personal and environmental factors |

|

|

Drugs |

BIQ |

|

Immediate family |

BIQ, SF-36 |

|

Health professionals |

BIQ |

|

Individual attitudes of immediate family members |

|

|

Social security services, systems and policies |

BIQ |

|

Individual attitudes of friends |

|

|

GAD-10: generalized anxiety disorder; MDI: Major Depression Inventory; SF-36: Short Form-36 Health Survey; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; CSQ: Coping Strategy Questionnaire; AMPS: Assessment of Motor and Process Skills; 6MWT: 6-Min Walk Test; Mob-T: Mobility Tiredness; BIQ: Basic Information Questionnaire; CPA: cuff pressure algometry. |

|

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs). PROs were based on self-administered questionnaires, all of which are in common use. For some of the applied instruments content comparison and linkage with ICF categories have been reported (13). A detailed description of the self-report instruments is set out in Appendix S11.

Physical function subscale of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ function). The physical function subscale in the original 1991 version of the FIQ, used in this study (16), is a 10-item questionnaire that contains 1 item related to walking ability (ability to walk several blocks), 8 items related to PADL and IADL (ability to do shopping, do laundry, prepare meals, wash dishes, vacuum a rug, make beds, drive a car, do yard work), and 1 item related to participation (ability to visit friends and relatives). It enquires as to which category “best describes how you did overall for the past week”. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale with the response options always (0), most times (1), occasionally (2) and never (3). In addition, the respondent is given the opportunity to answer “not applicable” if the item is not relevant. The FIQ activity subscale is scored by dividing the total score by the number of items answered and multiplying the value by 3.33. Thus the theoretical score range is 0 (no activity limitation) to 10 (maximum activity limitation). Appropriate psychometric properties of the FIQ and its subscales, based on a classical test paradigm, are reported in the literature (16). However, evaluated in a fibromyalgia population, Rasch analysis of the physical function subscale of the FIQ have indicated problems with scale structure, non-unidimensionality and systematic underestimation of disability by its handling of missing data (i.e. not applicable items) (20).

Physical functioning subscale of the SF-36 (SF-36 physical functioning). The physical functioning subscale of the SF-36 is a 10-item questionnaire that contains 5 items related to mobility (climbing several flights of stairs, climbing 1 flight of stairs, walking more than 1 mile, walking several blocks, walking 1 block), and 5 items related to activity and participation (lifting or carrying groceries, bathing or dressing oneself, making a bed, performing moderate activities (exemplified as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf) and vigorous activities (exemplified as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports). It enquires as to how much “your health now limits you in these activities”. Items are scored on a 3-point Likert scale with the response options Yes, limited a lot (1), Yes, limited a little (2), and No, not limited at all (3). Item responses are summed and the sum score transformed linearly into a 0–100 scale. The higher the score the less disability, i.e. a score of 0 is equivalent to maximum activity limitation and a score of 100 is equivalent to no activity limitation. The SF-36 has been widely used to assess health status, including functional ability in subjects with fibromyalgia (21). Psychometric evaluation of the SF-36 physical functioning subscale based on Rasch analysis, however, has indicated problems with scale structure, non-unidimensionality and ambiguous items when applied in this population (20).

Clinician-reported and observation-based outcomes

Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS). AMPS evaluations were performed by trained and calibrated AMPS raters from the Department of Occupational Therapy, Frederiksberg Hospital. The AMPS is a standardized observation-based assessment instrument that incorporates the use of Rasch analysis providing equal-interval linear measures of the quality of ADL task performance (22, 23). Two domains of ADL task performance are evaluated: ADL motor skills (moving self and objects) and ADL process skills (organizing and adapting actions). The ADL motor ability measure is an indication of how much effort, clumsiness and/or fatigue the person demonstrates when performing ADLs, and the ADL process ability measure is an indication of how efficient the person is when performing ADLs. ADL ability measures above the 2.0 logits (log-odds probability units) cut-off on the ADL motor scale and above the 1.0 logit cut-off on the ADL process scale indicate effortless, efficient, safe and independent ADL task performance in everyday life. The AMPS has been standardized on more than 150,000 persons internationally and cross-culturally, and several studies support good test-retest and rater reliability as well as validity, including in CWP populations (24).

Assessment of pressure pain threshold and tolerance. Pressure pain sensitivity was determined on the lower leg using computerized cuff pressure algometry (CPA). A detailed description of the test procedure is set out in Appendix S1. The following parameters were determined: Pain Threshold defined as the pressure of the cuff at the subject’s first sensation of pain when applying a constantly raising pressure (units kPa). Pain Tolerance defined as the pressure of the cuff when the pressure is switched off by the patient due to worst tolerable pain caused by pressure stimulation (units kPa) (25).

Baseline assessment also included a manual tender-point examination, measurements of maximal isokinetic knee muscle strength, maximal grip strength and a 6-Min Walk Test (6MWT) (see Appendix S1).

Other systematic data collection. Additional data regarding health and personal as well as environmental factors were collected in a standardized basic information questionnaire (BIQ), e.g. adjustment to job function and current employment status, social security and healthcare services, pain medication, family relationships, etc.

Statistical methods

Disease variables classified according to the ICF are presented as mean, standard deviation (SD), range and number of persons in the study population. The Spearman’s rank-order test was used to assess for correlations, with significance level < 0.01 to account for multiple comparisons. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was interpreted as follows: < 0.1: trivial, 0.1–0.3: weak; 0.31–0.5: moderate; 0.51–0.7: strong and > 0.7: very strong. This part of the data analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0. AMPS motor, AMPS process, FIQ function and SF-36 physical functioning outcomes were analysed with multiple regression models. The independent variables were comprised of all outcome variables listed in Table II, with the natural exception of the dependent variable and sum scores on the FIQ and SF-36 in regression models analysing FIQ function and SF-36 physical functioning as outcome. The models were reduced through standard significance testing using the Likelihood Ratio method. This procedure included only 155 out of the 257 participants, as many had missing values for 1 or more outcome variables. To increase statistical power, the reduced model was subsequently applied to the largest possible data-set, where only participants with missing observations for a factor in the reduced model were omitted. The reduced model was then expanded through a forward selection procedure. In the final models, 218, 253, 239 and 218 participants were included for AMPS motor, AMPS process, FIQ function and SF-36 physical functioning, respectively.

Results

Participants

A total of 257 females diagnosed with CWP (1990 – ACR definition) and AMPS evaluated as part of the baseline assessment were included in the study. The subjects’ mean age was 45.4 years (range 20.4–71.5) and mean symptom duration 123 months (range 6–540). In addition to CWP, 251 (97.7%) of the participants had a tender-point count ≥ 11, thereby also fulfilling the dual 1990 – ACR classification criteria for fibromyalgia (19).

Sample characteristics

Key variables classified according to the ICF model are shown in Table II. Evaluated in an ICF framework, participants were characterized by a high level of disease burden, although considerable individual variability was present. Within the body domain, high scores of pain, tiredness, fatigability, muscle stiffness, low pressure pain thresholds measured with CPA, and poor muscle power function were observed. Mean scores of anxiety, depression and pain catastrophizing were low to moderate and only 24 (9%) of participants fulfilled the criteria of severe depressive disorder according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10) algorithm for depressive symptomatology.

|

Table II. Variables from the overall study population classified according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model |

|||

|

Outcome variable |

Mean (SD) |

Range |

n |

|

Body |

|||

|

Muscle strength UE (PTQ extension) |

84.91 (36.45) |

7–199 |

243 |

|

Muscle strength UE (PTQ flexion) |

40.63 (18.24) |

5–85 |

243 |

|

Grip strength, max. |

174.81 (82.16) |

8–408 |

252 |

|

Vitality (SF-36) |

21.99 (17.50) |

0–75 |

255 |

|

Fatigue (FIQ) |

8.01 (1.95) |

1.3–10 |

254 |

|

Restedness (FIQ) |

7.56 (2.36) |

0–10 |

253 |

|

Wellbeing (SF-36) |

55.73 (20.67) |

0–100 |

255 |

|

Wellbeing (FIQ) |

7.34 (2.68) |

0–10 |

245 |

|

Anxiety (FIQ) |

4.44 (3.43) |

0–10 |

254 |

|

Anxiety (GAD-10) |

18.98 (9.73) |

1–50 |

255 |

|

Depression (FIQ) |

3.76 (3.41) |

0–10 |

255 |

|

Depression (MDI) |

21.47 (10.66) |

3–50 |

255 |

|

Bodily pain (SF-36) |

23.94 (15.18) |

0–84 |

255 |

|

Pain intensity (FIQ) |

7.08 (1.97) |

0–10 |

255 |

|

Muscle stiffness (FIQ) |

6.25 (2.77) |

0–10 |

252 |

|

Tiredness mobility (Mob-T) |

1.69 (1.60) |

0–6 |

251 |

|

Pain Threshold (PDT) |

12.25 (7.54) |

0.3–46.18 |

222 |

|

Pain Tolerance (PTT) |

31.94 (14.75) |

9.17–86.72 |

223 |

|

Activity and participation |

|||

|

ADL ability motor (AMPS) |

1.07 (0.50) |

0.04–2.82 |

257 |

|

ADL ability process (AMPS) |

1.09 (0.34) |

0.12–2.18 |

257 |

|

Walking speed (6MWT) |

452.09 (113.92) |

94.55–712.10 |

253 |

|

Function (FIQ) |

5.24 (2.23) |

0–9 |

254 |

|

Physical functioning (SF-36) |

42.50 (20.02) |

0–95 |

255 |

|

Role physical (SF 36) |

9.71 (21.39) |

0–100 |

254 |

|

Role emotional (SF-36) |

45.07 (43.14) |

0–100 |

250 |

|

Social functioning (SF-36) |

48.09 (26.59) |

0–100 |

255 |

|

Days of sick leave pr. week (FIQ) |

1.10 (1.71) |

0–5.71 |

65 |

|

Work ability (FIQ) |

6.70 (2.53) |

0–10 |

68 |

|

Personal |

|||

|

Catastrophizing (CSQ) |

15.86 (8.40) |

0–36 |

253 |

|

Perceived control over pain (CSQ) |

2.40 (1.38) |

0–6 |

253 |

|

Ability to decrease pain (CSQ) |

2.30 (1.20) |

0–6 |

251 |

|

Global measures |

|||

|

FIQ total |

61.23 (18.61) |

2.88–97.40 |

255 |

|

SF-36 PCS |

26.88 (6.78) |

8.79–50.68 |

255 |

|

SF-36 MCS |

40.77 (11.94) |

14.9–66.59 |

255 |

|

General health (SF-36) |

31.85 (18.19) |

0-97 |

254 |

|

GAD-10: generalized anxiety disorder; MDI: Major Depression Inventory; SF-36: Short Form-36 Health Survey; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; SF-36 PCS: SF-36 Physical Composite Score; PTQ: Peak Torque; SF-36 MCS: SF-36 Mental Composite Score; CSQ: Coping Strategy Questionnaire; AMPS: Assessment of Motor and Process Skills; 6MWT: 6-Min Walk Test; Mob-T: Mobility Tiredness. |

|||

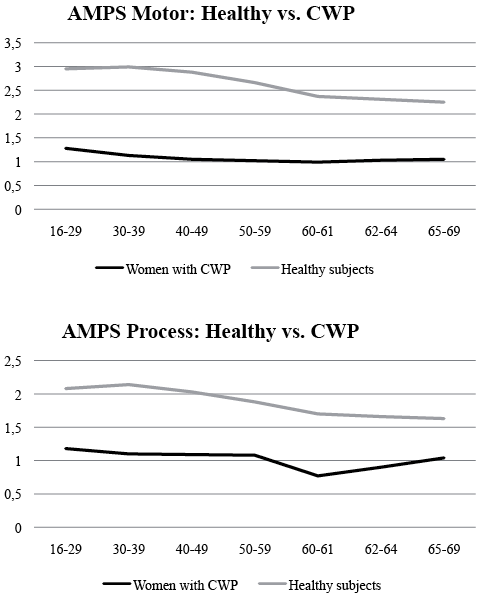

Within the activity and participation domains, the study population was characterized by high self-reported ratings of functional disability and a mean ADL motor ability measure on the AMPS below the 2.0 competence cut-off (mean 1.07, range 0.04–2.82). The mean ADL process ability measure was just above the 1.0 competence cut-off (mean 1.09, range 0.12–2.18), but none of the participants had ADL motor or ADL process ability measures above the age mean of healthy subjects of corresponding age (Fig. 1). Scores of social functioning and work ability were low. Eighty-two percent reported a change or permanent disability from usual working activity due to the pain condition, and 24% had claimed permanent disability pension at some stage during the disease course. Evaluated with the FIQ, only 68 (26%) of the participants reported having an occupational position outside the home and amongst those self-reported work interference was high (mean 6.7, range 0–10).

Fig. 1. Mean age activities of daily living (ADL) motor and ADL process ability measures in healthy subjects and study participants in the age range 20.4–71.5 years. The obtained mean age ADL motor and ADL process ability measures in the study population were all below age mean of healthy subjects of corresponding age, and the mean age ADL motor ability measure below the 1.5 logit competence cut-off, indicating individuals with potential need of assistance in everyday life in all age groups.

Relationship between observed functional ability and ICF variables

Correlations between AMPS ADL motor and ADL process ability measures, and ICF variables are summarized in Table III. Four ICF variables showed a moderate relationship with observed ADL motor ability and none met the criteria for a strong relationship. Moderate relationships were noted for the 6MWT (r = 0.40, p = 0.000), grip strength (r = 0.32, p = 0.000), and self-reported functional ability assessed with the FIQ (r = 0.31, p < 0.0001) and SF-36 (SF-36, r = 0.37, p < 0.0001). Relationships with pain, fatigue, and psychosocial variables were weak. No ICF variables met the criteria for a moderate or stronger relationship with observed ADL process ability.

Multivariate regression modelling with observed ADL motor ability as the dependent variable (n = 218) indicated statistically significant contributions from the 6MWT (mean effect 0.35, SD 0.151, p = 0.022), grip strength (mean effect 0.24 (0.072), p = 0.001), SF-36 physical functioning (mean effect 0.22 (0.075), p = 0.004), and the pressure pain threshold evaluated with CPA (mean effect 0.15 (0.048), p = 0.003). The coefficient of determination was calculated as R2 = 0.27. Multivariate regression modelling with observed ADL process ability as the dependent variable (n = 253) indicated statistically significant contributions from pain scored on VAS FIQ (mean effect: –0.18 (0.082), p = 0.026) and pain catastrophizing scored on the CSQ (mean effect –0.09 (0.043), p = 0041), but with a very low coefficient of determination; R2 = 0.06. Both models passed a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality (p > 0.1).

|

Table III. Variables classified according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model. Correlations between variables and Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) activities of daily living (ADL) motor and ADL process ability measures (n = 257) |

||||||

|

Outcome variable |

AMPS motor |

AMPS process |

n |

|||

|

Spearman’s rho r |

p-value |

Spearman’s rho r |

p-value |

|||

|

Body |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Muscle strength UE (PTQ extension) |

0.24 |

0.000 |

0.01 |

0.827 |

243 |

|

|

Muscle strength UE (PTQ flexion) |

0.27 |

0.000 |

0.11 |

0.098 |

243 |

|

|

Grip strength, max. |

0.32 |

0.000 |

0.14 |

0.026 |

252 |

|

|

Vitality (SF-36) |

0.17 |

0.008 |

0.06 |

0.345 |

255 |

|

|

Fatigue (FIQ) |

–0.09 |

0.139 |

–0.18 |

0.005 |

254 |

|

|

Restedness (FIQ) |

–0.14 |

0.031 |

–0.20 |

0.001 |

253 |

|

|

Wellbeing (SF-36) |

0.15 |

0.020 |

0.19 |

0.003 |

255 |

|

|

Wellbeing (FIQ) |

–0.20 |

0.001 |

–0.12 |

0.054 |

245 |

|

|

Anxiety (FIQ) |

–0.10 |

0.100 |

–0.17 |

0.007 |

254 |

|

|

Anxiety (GAD-10) |

–0.18 |

0.004 |

–0.18 |

0.005 |

255 |

|

|

Depression (FIQ) |

–0.11 |

0.071 |

–0.15 |

0.016 |

255 |

|

|

Depression (MDI) |

–0.17 |

0.008 |

–0.16 |

0.013 |

255 |

|

|

Bodily pain (SF-36) |

0.24 |

0.000 |

0.14 |

0.022 |

255 |

|

|

Pain intensity (FIQ) |

–0.21 |

0.001 |

–0.21 |

0.001 |

255 |

|

|

Muscle stiffness (FIQ) |

–0.14 |

0.026 |

–0.20 |

0.002 |

252 |

|

|

Tiredness mobility (Mob-T) |

0.28 |

0.000 |

0.16 |

0.010 |

251 |

|

|

Tender-point count |

–0.10 |

0.123 |

–0.07 |

0.290 |

257 |

|

|

Pain threshold (PDT) |

0.22 |

0.001 |

0.08 |

0.220 |

222 |

|

|

Pain tolerance (PTT) |

0.22 |

0.001 |

0.13 |

0.052 |

223 |

|

|

Activity and participation |

||||||

|

ADL ability motor (AMPS) |

1 |

0.31 |

0.000 |

257 |

||

|

ADL ability process (AMPS) |

0.31 |

0.000 |

1 |

257 |

||

|

Walking speed (6MWT) |

0.40 |

0.000 |

0.08 |

0.218 |

253 |

|

|

Function (FIQ) |

–0.31 |

0.000 |

–0.21 |

0.001 |

254 |

|

|

Physical functioning (SF-36) |

0.37 |

0.000 |

0.11 |

0.071 |

255 |

|

|

Role physical (SF 36) |

0.14 |

0.027 |

0.08 |

0.233 |

254 |

|

|

Role emotional (SF-36) |

0.13 |

0.035 |

0.10 |

0.105 |

250 |

|

|

Social functioning (SF-36) |

0.12 |

0.053 |

0.17 |

0.007 |

255 |

|

|

Days of sick leave pr. week (FIQ) |

–0.13 |

0.318 |

–0.04 |

0.743 |

65 |

|

|

Work ability (FIQ) |

–0.13 |

0.278 |

–0.11 |

0.382 |

68 |

|

|

Persons |

||||||

|

Catastrophizing (CSQ) |

–0.13 |

0.044 |

–0.20 |

0.002 |

253 |

|

|

Perceived control over pain (CSQ) |

0.11 |

0.091 |

0.17 |

0.009 |

253 |

|

|

Ability to decrease pain (CSQ) |

0.05 |

0.391 |

0.04 |

0.531 |

251 |

|

|

Global measure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIQ total |

–0.20 |

0.001 |

–0.24 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

SF-36 PCS |

0.24 |

0.000 |

0.07 |

0.266 |

255 |

|

|

SF-36 MCS |

0.12 |

0.061 |

0.15 |

0.016 |

255 |

|

|

General health (SF-36) |

0.13 |

0.040 |

0.13 |

0.035 |

254 |

|

|

Correlations > 0.30 (moderate) marked in bold. GAD-10: generalized anxiety disorder; MDI: Major Depression Inventory; SF-36: Short Form-36 Health Survey; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; SF-36 PCS: SF-36 Physical Composite Score; PTQ: Peak Torque; SF-36 MCS: SF-36 Mental Composite Score; CSQ: Coping Strategy Questionnaire; Mob-T: Mobility Tiredness; 6MWT: 6-Min Walk Test. |

||||||

Relationship between self-reported functional ability and ICF variables

Correlations between self-reported functional ability assessed with the FIQ and SF-36 and ICF variables are summarized in Table IV. Numerous ICF variables showed a moderate or stronger relationship with functional ability scored on both instruments. This included a strong relationship with pain, and moderate relationships with fatigue, mental wellbeing, psychological distress (anxiety, depression, catastrophizing) as well as self-reported social functioning and work disability. Relationships with observation-based measures obtained at the body level were moderate, although a strong relationship was noted for the SF-36 physical functioning and the 6MWT (r = 0.52, p < 0.0001). The relationship between self-reported functional ability assessed with the FIQ function and the SF-36 physical functioning was strong (r = 0.60, p < 0.0001), although not excellent.

|

Table IV. Variables classified according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model. Correlations between variables and self-reported functional ability measured with the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire ([FIQ) function and Short-Form 36 (SF-36) physical functioning (n = 257) |

|||||||

|

Outcome variable |

Function (FIQ) |

Physical functioning (SF-36) |

|||||

|

Spearman’s rho r |

p-value |

n |

|

Spearman’s rho r |

p-value |

n |

|

|

Body |

|||||||

|

Muscle strength UE (PTQ extension) |

–0.30 |

0.000 |

240 |

0.37 |

0.000 |

241 |

|

|

Muscle strength UE (PTQ flexion) |

–0.31 |

0.000 |

240 |

0.35 |

0.000 |

241 |

|

|

Grip strength, max. |

–0.34 |

0.000 |

249 |

0.34 |

0.000 |

250 |

|

|

Vitality (SF-36) |

–0.38 |

0.000 |

254 |

0.37 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

Fatigue (FIQ) |

0.41 |

0.000 |

253 |

0.37 |

0.000 |

254 |

|

|

Restedness (FIQ) |

0.37 |

0.000 |

252 |

0.31 |

0.000 |

253 |

|

|

Wellbeing (SF-36) |

–0.35 |

0.000 |

254 |

0.29 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

Wellbeing (FIQ) |

0.45 |

0.000 |

244 |

0.40 |

0.000 |

245 |

|

|

Anxiety (FIQ) |

0.34 |

0.000 |

253 |

–0.24 |

0.000 |

254 |

|

|

Anxiety (GAD-10) |

0.38 |

0.000 |

254 |

–0.29 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

Depression (FIQ) |

0.35 |

0.000 |

254 |

–0.27 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

Depression (MDI) |

0.42 |

0.000 |

254 |

–0.33 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

Bodily pain (SF-36) |

–0.52 |

0.000 |

254 |

0.54 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

Pain intensity (FIQ) |

0.50 |

0.000 |

254 |

–0.47 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

Muscle stiffness (FIQ) |

0.41 |

0.000 |

251 |

–0.39 |

0.000 |

252 |

|

|

Tiredness mobility (Mob-T) |

0.52 |

0.000 |

248 |

0.47 |

0.000 |

249 |

|

|

Tender-point count |

0.15 |

0.014 |

254 |

–0.19 |

0.003 |

255 |

|

|

Pain threshold (PDT) |

–0.08 |

0.266 |

219 |

0.18 |

0.007 |

220 |

|

|

Pain tolerance (PTT) |

–0.16 |

0.016 |

220 |

0.17 |

0.010 |

221 |

|

|

Activity and participation |

|||||||

|

ADL ability motor (AMPS) |

–0.31 |

0.000 |

254 |

0.37 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

ADL ability process (AMPS) |

–0.21 |

0.001 |

254 |

0.11 |

0.071 |

255 |

|

|

Walking speed (6MWT) |

–0.44 |

0.000 |

250 |

0.52 |

0.000 |

251 |

|

|

Function (FIQ) |

1 |

254 |

0.60 |

0.000 |

254 |

||

|

Physical functioning (SF-36) |

–0.60 |

0.000 |

254 |

1 |

255 |

||

|

Role physical (SF 36) |

–0.25 |

0.000 |

253 |

0.30 |

0.000 |

254 |

|

|

Role emotional (SF-36) |

–0.19 |

0.003 |

249 |

0.19 |

0.003 |

250 |

|

|

Social functioning (SF-36) |

–0.45 |

0.000 |

254 |

0.38 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

Days of sick leave per week (FIQ) |

0.38 |

0.002 |

64 |

–0.10 |

0.437 |

65 |

|

|

Work ability (FIQ) |

0.48 |

0.000 |

67 |

–0.48 |

0.000 |

68 |

|

|

Person |

|

||||||

|

Catastrophizing (CSQ) |

0.33 |

0.000 |

252 |

0.25 |

0.000 |

253 |

|

|

Perceived control over pain (CSQ) |

–0.18 |

0.004 |

252 |

0.18 |

0.004 |

253 |

|

|

Ability to decrease pain (CSQ) |

–0.23 |

0.000 |

250 |

0.19 |

0.002 |

251 |

|

|

Global measure |

|||||||

|

FIQ total |

0.63 |

0.000 |

254 |

–0.49 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

SF-36 PCS |

–0.50 |

0.000 |

254 |

0.73 |

0.000 |

255 |

|

|

SF-36 MCS |

–0.28 |

0.000 |

254 |

0.17 |

0.007 |

255 |

|

|

General health (SF-36) |

–0.39 |

0.000 |

253 |

0.31 |

0.000 |

254 |

|

|

Correlations > 0.30 (moderate) marked in bold. GAD-10: generalized anxiety disorder; MDI: Major Depression Inventory; SF-36: Short Form-36 Health Survey; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; SF-36 PCS: SF-36 Physical Composite Score; PTQ: Peak Torque; SF-36 MCS: SF-36 Mental Composite Score; CSQ: Coping Strategy Questionnaire; AMPS: Assessment of Motor and Process Skills; Mob-T: Mobility Tiredness; 6MWT: 6-Min Walk Test. |

|||||||

Multivariate regression modelling with the FIQ function as the dependent variable (n=239) indicated statistically significant contributions from FIQ wellbeing (mean effect: 1.16 (0.326), p = 0.000), tiredness mobility (mean effect: –0.41 (0.129), p = 0.000), SF-36 physical functioning (mean effect: –1.54 (0.263), p = 0.000), SF-36 general health (mean effect: –0.42 (0.195), p = 0.002), SF-36 social functioning (mean effect: –0.54 (0.215), p = 0.009), and FIQ pain (mean effect: 0.95 (0.433), p = 0.028). None of the observation-based measures entered the regression model as significant explanatory factors. The coefficient of determination was calculated as R2 = 0.55. Multivariate regression modelling with the SF-36 physical functioning as the dependent variable (n = 218) indicated significant contributions from SF-36 bodily pain (mean effect: 7.52 (1.798), p = 0.000), AMPS ADL motor ability (mean effect: 5.07 (2.311), p = 0.000), 6MWT (mean effect: 18.03 (4.500), p = 0.000), FIQ function (mean effect: –15.74 (2.805), p = 0.000), and self-reported work disability (mean effect: 7.87 (3.034), p = 0.01), with a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.53. Both regression models passed a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality (p > 0.1).

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that neither self-report of functional ability using standardized questionnaires nor surrogate measures of functioning obtained at the body level could substitute for observation-based assessment of ADL ability in patients with CWP. Furthermore, self-reported functional ability appears to show a significantly stronger relationship with pain and patients’ psychosocial profile, than does observation-based assessment.

As reported previously (15), the majority of women in our study population were characterized by low AMPS ADL motor ability, indicating considerable performance difficulties in everyday life. Although a wide range was observed in ADL ability, the mean AMPS ADL motor ability measure fell below the 1.5 logits cut-off, suggested to represent the competence cut-off for independent performance of ADL tasks in patients with musculoskeletal pain (26). However, the relationship with self-reported functional ability and observation-based measures of body functions, e.g. hand and knee muscle strength, and measures of mobility (6MWT), was only moderate. A moderate correlation between AMPS ADL ability measures and self-reported functional ability is not only observed in patients with CWP; such discrepancy, has also been demonstrated in patients with, for example, inflammatory rheumatic diseases (27, 28), supporting that instruments based on observation and self-report assess different aspects of functioning.

Research indicates a substantial heterogeneity and differences in patients’ adjustment to chronic pain and subsequent development of pain-related disability (6, 29). There is considerable evidence supporting that co-existence of depressive symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia is associated with increased pain intensity, functional disability, and poorer HRQoL (30). Improvement in physical and social functioning in the context of significant pain relief has also been reported in patients with fibromyalgia enrolled in pharmacological pain trials (31, 32). However, these associations between patient’s characteristics and associated symptoms and functional outcome have mainly been investigated using self-reported assessment of functional ability rather than objective assessment. The results of the univariate analyses in our study, indicates a weak association between observed ADL motor and process ability and the subjects’ level of pain and other psychosocial features, while a strong to moderate relationship was noted between these variables and self-reported measures of functional ability. This finding was supported by the results of the multivariate analyses that demonstrated a significant contribution from pain and psychosocial variables to the variability in self-reported functional ability, but not to the variability in the ADL ability measure of the AMPS. The influence of the patients’ psychosocial profile did, in particular, apply to the variability in self-reported functional ability on the FIQ, in which almost 55% of the variability was explained by pain and psychosocial variables, and in which no observation-based measures entered the regression model as significant explanatory factors.

Further support for using the AMPS to provide a more neutral and psychometrically robust measure of functional ability in CWP populations is provided by Rasch analyses of the FIQ function and SF-36 physical functioning subscales, which have shown problems with scale structure, non-unidimensionality and ambiguous items when applied to patients with fibromyalgia (20). Such serious shortcomings of the currently most widely used functional assessment questionnaires are likely to influence their usefulness in clinical practice, where functioning is an important target for intervention, and in studies focusing on functional outcomes and other important interrelationships. Questionnaire-based, self-reporting of functional ability evaluates the amount of perceived difficulty, but does not necessarily reflect the actual quality of task performance, such as measured with the AMPS. Consequently, the type of performance problems assessed by the respective instruments provide distinct, complementary information about ADL ability.

A poor agreement between self-report and observation-based assessment, and the influence of pain and psychological distress variables on self-reported functioning, has also been demonstrated in patients with acute and chronic low back pain (33–36), suggesting that this is an unambiguous problem across different pain populations. Observation-based assessment of functional ability could therefore prove a valuable addition to questionnaire-based assessment for clinical encounters; to determine the nature and extent of ADL task performance problems, and assist in setting goals and plan for interventions focused on improving ADL ability. Furthermore, it could prove a valuable addition when documenting change in functional status as an outcome of intervention, and in future research dedicated to discerning the nature of the complex interrelation between functioning and chronic pain.

The current study had some limitations. We sampled patients in a specialized tertiary care setting and the observed disease burden was high, including a high level of observed and self-reported functional disability. In addition, the study only included women. The study results may therefore not be generalizable to the overall referral population of CWP patients. Moreover, the cross-sectional study design did not allow any conclusions about directions of the observed relationships between disability measures and ICF variables.

In conclusion, the results of this study support the notion that self-reported functional ability and observation-based assessments obtained at the body level cannot substitute for observation-based assessment of ADL ability in CWP populations. They measure different aspects of functioning and offer distinct and supplementary information. Patients’ perception of functional ability may be related to other factors associated with the pain problem, including patients’ pain-related beliefs and ability to adjust to chronic pain. In contrast to the self-reported scores of functional ability, the observation-based ADL ability measures provided by the AMPS showed no relationship with psychosocial variables, indicating that functional ability measured with the AMPS is less influenced by such factors. It is therefore suggested to include valid observation-based assessment methods, such as the AMPS, in the clinical assessment of patients with CWP and future clinical pain and rehabilitation studies addressing functional outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from The Oak Foundation, Aase og Ejnar Danielsens fond, The Schioldann Foundation, The Danish Rheumatism Association, The A. P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science, Minister Erna Hamiltons Legat for Videnskab og Kunst and Støtteforeningen for Gigtbehandling og Forskning ved Frederiksberg Hospital. The authors thank the research staff at the Parker Institute, the staff at the Department of Rheumatology and the occupational therapists at Department of Occupational Therapy, Frederiksberg Hospital for contributing to the data collection.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1http://www.medicaljournals.se/jrm/content/?doi=10.2340/16501977-1878

References