Jill I. Cameron, PhD1,2,5, Marina Bastawrous, MSc2, Amanda Marsella, MSc, Samantha Forde, MScOT1, Leslie Smale, MScOT1, Judith Friedland, PhD1,2, Denyse Richardson, MD3,5 and Gary Naglie, MD3,4,5,6

From the 1Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, 2Graduate Department of Rehabilitation Science, 3Department of Medicine, and 4Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, 5Department of Research, UHN – Toronto Rehabilitation Institute and 6Department of Medicine and Rotman Research Institute, Baycrest Health Sciences, Toronto, Canada

OBJECTIVE: To explore stroke survivors’, caregivers’, and health care professionals’ perceptions of weekend passes offered during inpatient rehabilitation and its role in facilitating the transition home.

DESIGN: Qualitative descriptive.

SUBJECTS: Sixteen stroke survivors, 15 caregivers, and 20 health care professionals’ from a rehabilitation hospital.

METHODS: Participants discussed their perceptions of the purpose of the weekend pass, experiences with the weekend pass including supports needed, and weekend pass administration. Focus group and interview data were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, checked for accuracy, and analyzed using conventional content analysis.

RESULTS: We identified 3 key themes: i) preparing for patients to be safe at home; ii) gaining insight through the weekend pass; and iii) the emotional context of the weekend pass. These themes varied by participant group.

CONCLUSIONS: When offering weekend passes, stroke care systems should carefully consider patients’ and caregivers’ readiness, emotional state, and preparation for weekend passes. The weekend pass experience can inform in-patient therapy, provide patients and caregivers with insight into life after stroke, and help prepare patients and families for the ultimate transition home.

Key words: stroke; rehabilitation; caregiver; transitions; health care professionals; health service delivery; qualitative.

J Rehabil Med 2014; 46: 00–00

Correspondence address: Jill Cameron, Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, 160-500 University Ave., Toronto, ON M5G 1V7, Canada. E-mail: jill.cameron@utoronto.ca

Accepted Apr 17, 2014; Epub ahead of print Aug 28, 2014

Introduction

Individuals who experience a stroke utilize many elements of the health care system including emergency department, acute hospital, inpatient rehabilitation, community, and long-term care services. Unfortunately, these elements tend to lack a common coordinating system (1) and stroke survivors and family caregivers are often left to manage their movement across these diverse care environments (2). Patients and their caregivers suggest the transition home is the most challenging (3, 4). Many stroke survivors and caregivers feel anxiety, a lack of preparedness, and a sense of abandonment as they return to the community (5, 6). Strategies to improve the transition home would not only benefit stroke survivors and their caregivers but could also reduce hospital readmissions, home care demands, and overall health care costs (7).

Since the early 1970s, weekend passes (WPs) have been recommended as a method to facilitate stroke survivors’ transition home (8). A WP typically entails stroke survivors going home under the supervision of their family from Friday to Sunday evening. For many health care organizations, WPs have become standard practice, but we were not able to identify any research examining their impact on the transition home, or on stroke survivors’, family caregivers’ or health care professionals’ (HCPs) experiences with them.

The objective of our research was to obtain an in-depth understanding of patients’, family caregivers’, and HCPs’ perception of WPs and its role in facilitating the transition home.

Methods

Study design

A qualitative descriptive approach was used to obtain a rich and in-depth account of participants’ perspectives on the WP and to develop a data-near report (9–11).

Recruitment and sample

The research was conducted at a rehabilitation facility in a large urban center where WPs are a standard element of their in-patient program. The study protocol was approved by the University’s and rehabilitation facility’s research ethics boards. Members of the research team approached, recruited, and interviewed consecutive patients and caregivers during the week following the first WP. Second interviews took place approximately 4 weeks after patients had been fully discharged home. HCPs affiliated with the stroke team were invited to participate in one of 3 focus groups or an in-depth interview. All participants provided written consent.

Data collection

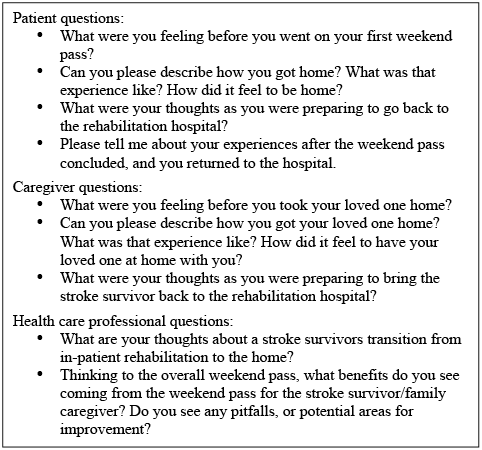

A series of open-ended questions and probes specific to each participant group encouraged participants to discuss their general perception of and experience with the WP (12). Questions explored WP experiences, delivery, preparation, and relation to the transition home. Sample questions for each group are presented in Fig. 1. The interviews and focus groups were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, and reviewed for accuracy.

Fig. 1. Sample questions for each participant group.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using conventional content analysis (13, 14). Multiple authors were involved in the data analysis to decrease the chance of individual biases influencing the research findings (15). Authors reviewed each transcript while listening to audio files to become immersed in the data, drafted a code book capturing the key topics being discussed, used open coding to code the key messages in each passage, used axial coding to organize the codes into common groupings, and began to identify the themes (13). NVivo qualitative software was used to manage and code the data (version 2.0 QSR International PTY Ltd).

Results

Sixteen patients and 15 caregivers completed the first interview, in the rehabilitation facility and by phone respectively, and we were able to reach 11 patients and 11 caregivers by telephone to complete second interviews. Three focus groups and one interview were conducted with 20 HCPs in the rehabilitation facility. We did not have permission to go into the patient records to collect detailed data about their medical conditions. Tables I–III summarize participant characteristics.

We identified 3 key themes: i) preparing for patients to be safe at home; ii) gaining insight through the WP; and iii) the emotional context of the WP. The themes are discussed below, highlighting similarities and differences between participant groups and using quotations as examples.

|

Table I. Patient characteristics (n = 16) |

|

|

Characteristic |

|

|

Female, n |

12 |

|

Age, years, median (range) |

62 (25–91) |

|

Weekend passes per patient, median (range) |

3 (1–6) |

|

Stroke-related impairmenta, n |

|

|

Ambulation |

7 |

|

Balance |

3 |

|

Right-sided weakness |

7 |

|

Left-sided weakness |

2 |

|

Cognitive deficits |

3 |

|

Speech |

1 |

|

Vision |

1 |

|

aPatients may have more than one impairment. |

|

|

Table II. Caregiver characteristics (n = 15) |

|

|

Characteristic |

|

|

Female, n |

13 |

|

Age, years, median (range) |

41 (23–75) |

|

Caring for, n Parent Partner/spouse Grandparent/friend |

10 3 2 |

|

Table III. Health care professional disciplines (n = 20) |

|

|

Profession |

n |

|

Occupational therapists |

3 |

|

Physiotherapists |

3 |

|

Social workers, service coordinator |

3 |

|

Nurses |

3 |

|

Pharmacists |

3 |

|

Speech language pathologists |

2 |

|

Recreation therapists, dietician, occupational therapy students |

3 |

Theme 1: Preparing for patients to be safe at home

Preparing for patients to be safe at home entailed first determining who was ready to participate in a WP and, second, preparing patients and families to be safe at home. HCPs emphasized the collaborative nature of assessing readiness and preparing patients and families for a WP. Patients agreed that safety while at home was of central importance, but also wanted more emphasis on safety regarding engaging in social and recreational activities. Caregivers discussed needing to feel better supported and prepared by the health care team to ensure they were able to safely care for the patient at home.

Assessing patient readiness. Patients and family caregivers did not discuss readiness except for noting that their recovery must be progressing if they were ready to go on a WP. This theme was primarily discussed by HCPs who commonly collaborated to obtain a holistic picture of patients’ abilities and, therefore, readiness for a WP. This included considering patients’ medical stability, the suitability of the home to accommodate their abilities and needs, and the availability of a family member to provide assistance in the home as needed. Patient mobility around the home, a key safety concern, motivated collaboration between occupational (OT) and physical (PT) therapists. Together they assessed the home environment by discussing it with the patient or family, viewing photographs, or, in a few cases, visiting the home. In some situations, OTs and PTs worked with nursing and other staff members to ensure patients were loaned any supports (e.g., commode) they may need for the weekend. If patients were not able to fully care for themselves and family support was not available, a WP was not recommended. HCPs noted the importance of family support especially since community care services were not available to patients who were not yet formally discharged from in-patient care. The following is an example of the team’s collaborative involvement in planning a patient’s WP:

“It’s never just one of us that is addressing the problem, if the whole team works together so that we can problem solve together, brainstorm together a little bit – often with the family member and the patient – we can come up with hopefully the best ideas, the best solutions possible” (Participant 1, focus group 3).

Preparing patients and families for a weekend pass. Most patients felt adequately prepared to be safe in their home; however, some patients wanted HCPs to better prepare them for the practical (e.g., performing everyday activities) and social (e.g., having visitors, dining out) elements. This included information regarding adjusting to lifestyle changes such as over-exertion and physical capacity. Patients also discussed needing more preparation regarding the expectations they and their family members should have of them in the home (i.e., what they can/should do independently vs with assistance). In addition, some patients recommended that these types of instructions be provided in written format to easily refer to while at home. The following provides an example of the suggestions made regarding the preparation they would have liked to receive prior to going on the WP:

“It would have been helpful last weekend … if there’s something that was given out to patients so that they would just generally know not to try to do too much even though it didn’t seem like too much. Like, just some general rules about how certain things that would have seemed easy before might seem really overwhelming and tiring now” (Patient 3, interview 1).

Family caregivers recognized that once home, patients’ safety became their responsibility. As a result they wanted aids and devices to be in place prior to the WP and training to meet patients’ needs for physical and emotional support. Family caregivers reported not feeling confident in their new role because they did not feel adequately prepared. They felt they could be better prepared if HCPs set time aside to educate and train families and included them in therapy. The following caregiver summarizes families’ need to be informed and involved in patient care:

“I think it’s good for the family to be involved and to know what’s going on. I realize that when you are dealing with the public some of them don’t know what you’re talking about and some of them don’t care. But I think that the majority of us want to know what’s going on … and if we don’t understand it immediately then we need to have it explained to us in some terms that we do. We all need to be involved in our own health care, and we need to be involved in whatever needs to happen for people for whom we’re taking at least some responsibility for” (Caregiver 14, interview 2).

HCPs discussed the strategies used and perceived challenges associated with preparing families for a WP. The stroke team used family conferences to discuss patients’ progress, functional abilities, therapy, and discharge care plans. HCPs also discussed several challenges in relation to preparing families. Firstly, with no formal resources on WPs, HCPs felt families may not fully understand its scope and importance. HCPs also felt many families were too overwhelmed to accept training from HCPs. In some situations (e.g., rehabilitation admission that occurs late in the week), a last minute decision about who would receive a WP can be made by a senior member of the team. In these situations, HCPs discussed not having time to properly prepare patients and their families for the WP, potentially compromising patient safety. As a result, HCPs were not always confident that families were adequately prepared for the WP. The following describe how family conferences could be improved and some of the challenges associated with involving families in therapy:

“Maybe we need to add that level of importance to [the WP] and make sure the teaching component is enhanced and all professions are working together to make sure that [the family] get it – that it’s an important thing. Because we certainly let them know about how important the family conference is and so forth, maybe we just need to shine the light on [the WP] a little bit more in a formalized way” (Participant 7, focus group 2).

“It’s really, really dependent on the family and … I don’t want to say their level of involvement, but their readiness to be involved..certainly in this stage … acute rehab and a lot of families are really, really overwhelmed and really nervous and they don’t necessarily … it’s not that they don’t want to help, it’s just that they can’t kind of get their heads around helping and they would rather us sort of fix the patient rather than have to participate [in therapy]” (HCP interview).

Theme 2: Gaining insight through the weekend pass

Patients, caregivers, and HCPs discussed the WP as being an important learning opportunity to facilitate patients’ ultimate transition home. They felt the WP provided insight for patients and families as to what life could look like once patients return home and for HCPs to inform further therapy in the in-patient setting.

Weekend pass provides patients and families with insight into their abilities and care needs in the home. Patients viewed the WP as an opportunity to apply the skills and knowledge they gained during rehabilitation in the “real-world” setting of their home. By applying these skills at home, patients were able to learn about their abilities as well as the barriers and obstacles they experienced outside of the hospital environment. Patients returned to the hospital motivated to engage in therapy to ultimately facilitate the transition home. The following captures patients’ gaining of insight while on a WP:

“When people get home, they realize what they can do and what they can’t do, their limitations, and they realize, okay, this is what I need to work on” (Patient 1, interview 2).

The patients who experienced multiple WPs felt that there was an opportunity between each one for HCPs to resolve any issues that arose on weekends. In the follow-up interviews, these patients expressed improvement with each WP and that this ultimately made the transition home easier. Patients who only went on one WP did not discuss improvement over time and its relation to the transition home. The following captures a patient’s experience with multiple WPs:

“It [first WP] was hard because I couldn’t do much, I couldn’t walk properly or anything, but the last weekend was much easier because I was able to do a lot more… get up the stairs, get in the shower… and it made me see what I can and cannot do…” (Patient 7, interview 2).

The WP also provided families with the opportunity to practice caring for the patient in the home environment, without the direct assistance of hospital staff, so they could learn what to expect once the patient is discharged. As a result, families gained confidence and felt less fearful about the post-discharge situation. The following highlights a caregiver’s perspective of the impact of the WP:

“I was happy to get [patient] home and see how she was doing, knowing that if I was concerned, I could give her back and… get some tune ups, before she was home so to speak” (Caregiver 14, interview 2).

Weekend pass informs future in-patient therapy sessions. Patients, caregivers, and HCPs felt the WP experience informed future therapy sessions. Patients and caregivers believed therapy could address difficulties experienced during the WP. Use of the WP to inform therapy was discussed primarily by HCPs who modified therapy to specifically address challenges experienced by patients during the WP. For this reason, HCPs emphasized the importance of both patients and families providing feedback about the WP experience, especially since their perspectives may differ. HCPs sometimes had difficulty obtaining and, therefore, using families’ experiences during the WP to inform therapy. Prior to the WP, families received an evaluation form to record their WP experience, but the forms were not routinely completed. HCPs also tried to obtain feedback directly from families, but noted that their caseload and work hours (weekdays from 8 am to 4 pm) limited their opportunities to directly interact with some caregivers who might be at work themselves during that time. Nurses receiving patients on a Sunday evening often asked ‘how the weekend went’ but patient and family responses were not documented in any formal way. HCPs suggested developing a more formal re-admission procedure where nurses would ask and document answers to a series of questions. The following highlights the need for a more formal follow-up process:

“I think … when they come back … [there should be] more of a formula that nurses go through, whether you’re a relief nurse here or not, it’s a standard procedure … it’s not just a dump off and that’s the end of it …” (Participant 2, HCP focus group 3).

Theme 3: The emotional context of the weekend pass

Patients and family caregivers experienced a variety of emotions and discussed how their emotions changed over time. This theme was not discussed by HCPs. Before the first WP, patients reported mixed feelings of excitement, nervousness, and anxiety. Many patients were happy to return to their home and were excited to see their friends and family. However, some expressed concern about being left alone, having another stroke, experiencing too much stimulation, or being unable to cope with the physical barriers of the home. Several patients were also worried that their families would not be cognizant of their limitations and, in turn, would expect more of them than they could manage.

During the WP, patients reported being very happy to be in a familiar environment, to see their family and friends, and to have the break from the regimentation of rehabilitation. Conversely, some individuals reported visitors and visual and/or auditory stimulation (e.g., children screaming, television) were overwhelming and extremely tiring. Many found it difficult to adjust to the environmental barriers (e.g., using stairs, cooking in the kitchen) of the home. The fear of falling, general safety in the home, and having another stroke continued to contribute to patient nervousness. After the WP, many patients were unhappy to leave their family. In contrast, a number of patients reported feeling very excited to continue their rehabilitation in order to reach the final goal of transitioning home. The following highlight the mixed emotions patients reported feeling prior to and during the WP, respectively:

“I was looking forward to it [WP] but I was also nervous a little bit because … especially in my situation … my physical deficits are not so noticeable … But in general with my husband, I didn’t want him to sort of … expect too much of me … not to load too much on me, physically or emotionally” (Patient 3, interview 1).

“My nephew is very high strung, so while he was a joy to have around … I found since the stroke I find it really difficult to have lots of different things happening … so with my nephew … after about 10 minutes I started getting really agitated and started snapping, I felt like I wanted to cry and I just got completely overwhelmed.” (Patient 16, interview 1).

Caregivers primarily described negative emotions associated with the WP. Before the WP, they were commonly nervous about bearing full responsibility for the physical and emotional care of the patient and managing their medications. They were unsure of their abilities to care for the patient and to keep them safe. During the WP, caregivers were happy to have the patient home but many continued to experience mixed emotions. Caregivers’ new responsibilities, including providing physical and emotional support, being constantly vigilant, and bearing sole responsibility for patient safety, often left them feeling emotionally drained. Caregivers were happy when they received support from others – including HCPs, family members, friends, and neighbors – and they experienced stress when these supports were not in place. After the WP, caregivers reflected on some of the benefits. They felt that the nervousness they experienced “melted away” with subsequent WPs and noted that they learned by doing. As a result, caregivers felt better adjusted after the WP experience and acknowledged that it was worth enduring the challenges for the benefit of the patient. The following captures caregivers’ common emotional response prior to and during their first WP experiences, respectively:

“I was kind of anxious [to bring patient home]… I shouldn’t say kind of – I was very anxious” (Caregiver 13, interview 1).

“I wouldn’t say difficult maybe sometimes a little frustrating … because I’m trying … I’m trying to keep his spirits up… and I have to keep explaining that everything is good, and you know the worst is over, I’m trying to get him to focus on just getting better, going through his therapy … and getting better. It’s a little bit hard” (Caregiver 4, interview 1).

Discussion

As stroke best practice guidelines are beginning to emphasize patient and family caregiver support through transitions, our study of the WP can inform application of these guidelines (16–18). Given our inability to identify previous research on the WP, our qualitative study with patients, family caregivers, and HCPs provides insight into benefits and areas for improvement. The first theme emphasized patient safety in the home including the need to assess patients’ readiness and prepare patients and families. The second theme reflected the WP’s role as a facilitator of patients’ final transition home by patients, families, and therapists obtaining insight as to patients’ future therapy and care needs. In the final theme, patients and caregivers emphasized the emotional context in which WPs occurred and how these experiences changed over time.

As discussed by our participants and consistent with previous research, patient safety post-stroke is a priority especially in relation to discharging patients back to the community (19). For example, early supported discharge programs, where patients are supported by a health care team as soon as they arrive home, emphasize patient safety when making the decision about patient eligibility for early supported discharge (19). In our study, HCPs raised a number of concerns that may threaten their ability to ensure patient safety. One central concern was their ability to adequately prepare patients and families prior to the weekend, which could be compromised by: i) last minute decisions to offer WPs and ii) family members’ availability and readiness to be trained. Formalizing the procedure for offering WPs, including the number of days prior to the weekend when the decision has to be made, can minimize the concerns associated with last minute passes. Adopting alternate care delivery models, such as 7-day per week rehabilitation (20), can be tested to determine if therapists being more readily available at times when families are also available results in families receiving appropriate preparation. In addition, incorporating some of the principles of early supported discharge programs, including therapists completing pre-discharge home inspections, providing multi-disciplinary nursing and rehabilitation home care services during a WP, and educating caregivers about specific patient safety concerns, have the potential to minimize threats to patient safety (21–23).

Patients felt that they received adequate preparation to be safe at home, but would have liked preparation for resuming usual activities and support regarding the emotional aspect of the WP. Community re-integration and resumption of meaningful roles are often secondary goals in rehabilitation (24, 25). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (26) provides a theoretical framework to broaden our view of rehabilitation beyond functional outcomes to include participation. Future research would benefit from exploring the barriers and facilitators to including community reintegration as part of discharge preparation and its impact on transition experiences and long term outcomes for life in the community post-stroke.

Caregivers in our study described their responsibility for patient safety and meeting the patients’ physical and emotional care needs. Caregiver who were not adequately supported or prepared for this role described the weekend pass experience as overwhelming. Previous studies have demonstrated that overwhelmed stroke caregivers can result in increased utilization of healthcare resources and premature institutionalization of the patient (27). In our study, access to supportive resources (e.g., support from family members, friends, and HCPs; access to tangible supports, such as home modifications and assistive devices) was perceived as increasing caregivers positive experiences. This observation is supported by previous research that suggests supporting caregivers in the community contributes to positive caregiver adjustment, as well as higher levels of wellbeing and general health (28).

Patients’ uncertainty about their capabilities (29), poor discharge planning (24) and the absence of medical follow-up (30) often leave patients ill-prepared for their final transition home and, as a result, the transition is often difficult (24). For stroke survivors, the WP gives them the opportunity to apply and practice what they have learned during in-patient rehabilitation in the ‘real-life’ context of their own homes before ultimate discharge. As participants in this study discussed, this experience provides patients and families with insight into what they can and cannot do as they are preparing to return to the community. They also suggested that experiencing multiple WPs further enhanced their preparation for the transition home. Since the WP occurs while the patient is still receiving in-patient rehabilitation, HCPs can learn from WP experiences and adjust subsequent therapy sessions and discharge planning accordingly. Unfortunately, HCPs found it challenging to obtain feedback from families and, therefore, suggested a more formal follow-up procedure including questions that could be routinely asked and documented in the chart by re-admitting nurses.

Though our study captured insights from patients, caregivers, and HCPS, future research may benefit from exploring perspectives from a variety of institutions as opposed to a single healthcare site as was done in the current study. In addition, future research may also obtain physicians’ (not included in this study) thoughts on the WP aspect of in-patient stroke rehabilitation. These findings also do not reflect the experiences of non-English speaking patients and caregivers.

Findings from this qualitative study with patients, family caregivers, and HCPs suggest the WP has therapeutic value. HCPs aimed to ensure patients would be safe at home by assessing their readiness and preparing patients and families for a WP. Patients wanted specific preparation to manage the social and emotional aspects of going home for the weekend. Caregivers needed more preparation and support to minimize their feelings of being overwhelmed during the weekend. All participants felt they gained insight as a result of the WP; experiencing multiple WPs made adjustment easier and contributed to the transition home. Both patients and caregivers needed more support for the emotional consequences of the WP. Enhancing the process for offering WPs is one way to help patients and families manage one of the most challenging of transitions within the health care system – the transition home.

Acknowledgements

Participating stroke survivors, family caregivers, and health care professionals; members of stroke care teams who assisted with recruitment are gratefully acknowledged.

This study was founded by Ontario Stroke Network Research Grant. Jill Cameron is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award. Gary Naglie is supported by the George, Margaret and Gary Hunt Family Chair in Geriatric Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References