Annie Palstam, MSc1,2, Anette Larsson, MSc1,2, Jan Bjersing, MD, PhD1, Monika Löfgren, PhD3, Malin Ernberg, PhD4, Indre Bileviciute-Ljungar, MD, PhD3, Bijar Ghafouri, PhD5,6, Anna Sjörs, PhD5, Britt Larsson, MD, PhD5, Björn Gerdle, MD, PhD5, Eva Kosek, MD, PhD7 and Kaisa Mannerkorpi, PhD1,2

From the 1Department of Rheumatology and Inflammation Research, Institute of Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, 2University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-centred Care (GPCC), Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg, 3Department of Clinical Sciences Danderyd Hospital, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, 4Department of Dental Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Huddinge, 5Rehabilitation Medicine, Department of Medicine and Health Sciences (IMH), Faculty of Health Sciences, Linköping University and Pain and Rehabilitation Centre, County Council of Östergötland, Linköping, 6Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Linköping University and Centre of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, County Council of Östergötland, Linköping and 7Department of Clinical Neuroscience and Osher Center for Integrative Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

OBJECTIVE: To investigate perceived exertion at work in women with fibromyalgia.

DESIGN: A controlled cross-sectional multi-centre study.

Subjects and methods: Seventy-three women with fibromyalgia and 73 healthy women matched by occupation and physical workload were compared in terms of perceived exertion at work (0–14), muscle strength, 6-min walk test, symptoms rated by Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), work status (25–100%), fear avoidance work beliefs (0–42), physical activity at work (7–21) and physical workload (1–5). Spearman’s correlation coefficient and linear regression analysis were conducted.

RESULTS: Perceived exertion at work was significantly higher in the fibromyalgia group than in the reference group (p = 0.002), while physical activity at work did not differ between the groups. Physical capacity was lower and symptom severity higher in fibromyalgia compared with references (p < 0.05). In fibromyalgia, perceived exertion at work showed moderate correlation with physical activity at work, physical workload and fear avoidance work beliefs (rs = 0.53–0.65, p < 0.001) and a fair correlation with anxiety (rs = 0.26, p = 0.027). Regression analysis indicated that the physical activity at work and fear avoidance work beliefs explained 50% of the perceived exertion at work.

CONCLUSION: Women with fibromyalgia perceive an elevated exertion at work, which is associated with physical work-related factors and factors related to fear and anxiety.

Key words: work ability; fibromyalgia; tender points; chronic pain; physical capacity; physical workload.

J Rehabil Med 2014; 46: 773–780

Correspondence address: Annie Palstam, Department of Rheumatology and Inflammation Research, Guldhedsgatan 10 A, SE-405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: annie.palstam@gu.se

Accepted Mar 27, 2014; Epub ahead of print Jul 30, 2014

INTRODUCTION

Fibromyalgia (FM) is associated with a substantially increased risk of sickness absence and imposes a heavy patient burden in terms of disability, loss of quality of life, and costs (1–3). FM also imposes an economic burden on society in terms of loss of productivity, mostly due to sick leave and disability pensions (1–3).

The prevalence of FM in the general population ranges from 1% to 3%, it is more common among women and increases with age (4, 5). The degree of employment in FM varies geographically, with a range from 34% to 77% in different studies (6). This wide range is related to differences in the social benefit systems and labour markets of different countries (6). FM is characterized by persistent widespread pain, increased pain sensitivity and tenderness (7). Other associated symptoms are fatigue, psychological distress (4, 7), impaired physical capacity (8–10) and activity limitations (11).

Working women with FM are reported to experience better health in terms of symptom severity and quality of life than non-working women with FM (12–15). Furthermore, work is an important factor for health in women with FM (16). However, exposure to high physical demands at work is a risk factor for work disability in the general working population (17, 18) as well as in musculoskeletal pain conditions (6, 19, 20). Depending on individual differences in health status and physical capacity among workers, exertion at work can be assumed to be perceived differently despite similar physical demands at work. Physical demands at work exceeding worker’s physical capacity is a risk factor for long-term sick leave in the general working population (21, 22) and has been reported to be a prognostic factor for longer sickness absence in non-specific musculoskeletal disorders (23). Thus, perceived exertion at work may be of importance for work ability in the general population as well as in FM. We hypothesize that perceived exertion at work is higher in women with FM than in healthy women.

The aims of this study were: (i) to investigate whether perceived exertion at work is higher in women with FM than in healthy women matched by occupation and physical workload; and (ii) to study explanatory factors for perceived exertion at work.

METHODS

Study design

A controlled cross-sectional multi-centre study.

Participants

This is a sub-study of an ongoing multi-centre experimental study comprising women with FM and healthy women (ClinicalTrials.gov identification number: NCT01226784).

Inclusion criteria for women with FM were: to be of working age, 20–65 years, and meeting the ACR-1990 classification criteria for FM (7). Exclusion criteria were: high blood pressure (> 160/90 mmHg), osteoarthritis in the hip or knee, other severe somatic or psychiatric disorders, primary causes of pain other than FM, high consumption of alcohol (Audit > 6), participation in a rehabilitation programme within the past year, regular resistance exercise training or relaxation exercise training more than twice a week, inability to understand or speak Swedish, and not being able to refrain from analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or hypnotics for 48 h prior to examination.

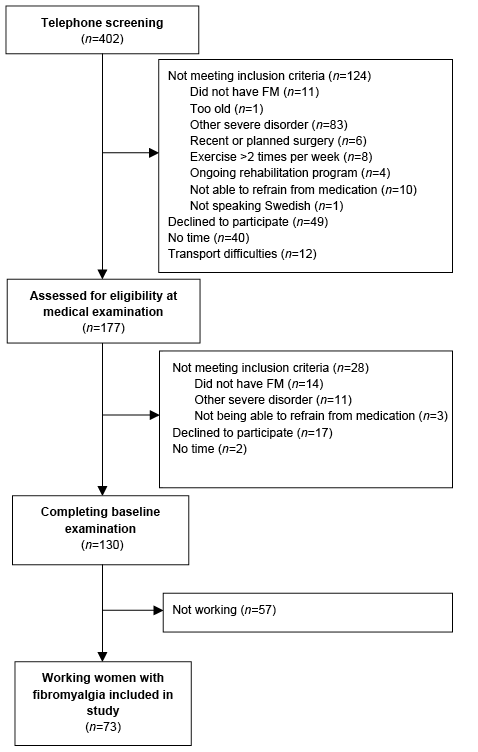

Participants were recruited via advertisements in the local newspapers of 3 cities in Sweden (Gothenburg, Stockholm and Linköping). A total of 402 women notified their interest in participating in the study and were telephone screened for possible eligibility. Out of these women, 225 were not eligible for enrolment. The remaining 177 women were assessed for eligibility at a medical examination, and 44 were found not eligible for further enrolment. A total of 133 women with FM were thus included in the multicentre experimental study. In this study, only working women were included in the analyses, leaving a total of 73 women with FM, with an age range from 22 to 63 years (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Recruitment process of the women with fibromyalgia (FM).

A total of 73 healthy women, age range 21–63 years, were included in this study as matched controls. They were matched with the FM group by occupation and physical workload (1–5) using the following standard classification system: 1 = heavy work, 2 = heavy repetitive work, 3 = medium heavy work, 4 = light repetitive work, and 5 = light (administrative) work (24). The matching resulted in 13 different occupational categories with similar work tasks and matching physical workload according to the 1–5 scale described above. The matching fitted for 71 out of the 73 women with FM. The 2 remaining women were matched by similar work tasks, and matching physical workload. None of the participants had a heavy (1) or a heavy repetitive (2) physical workload. Twenty-seven women (37%) in each group had a medium heavy physical workload (3), 2 women (3%) in each group had a light repetitive physical workload (4), and 44 women (60%) in each group had a light physical workload (5).

Data collection

Demographic data including work status were gathered in a standardized interview. Clinical assessments of tender points by manual palpation (7) were conducted on the women with FM by trained examiners to verify FM diagnosis according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR 1990) criteria for FM (7). The women completed a battery of questionnaires and performed 4 tests of physical capacity, described in detail below.

Measures

Physical capacity. Grippit (AB Detektor, Göteborg, Sweden) is an electronic instrument that measures hand-grip force. The mean force over a set period of time (10 s) was recorded (25).

Isobex (Medical Device Solutions AG, Oberburg, Switzerland) is an electronic instrument that measures isometric strength, here in the upper arm flexors. The maximum strength during a period of 5 s was recorded.

Steve Strong (Stig Starke HBI, Göteborg, Sweden) is an electronic instrument that measures isometric strength in the quadriceps muscles. The maximum strength during a period of 5 s was recorded. This instrument has been used in previous studies of physical performance.

The 6-min walk test (6MWT) is a performance-based test that measures total walking distance during a period of 6 min (26). The 6MWT is considered a useful representation of physical capacity and endurance in daily life.

The Leisure Time Physical Activity Instrument (LTPAI) is an instrument assessing the amount of physical activity performed during a typical week. The total score is the sum of the activities (27).

Symptoms. Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) is disease specific and comprises 10 subscales of disabilities and symptoms, ranging from 0 to 100. The total score is the mean of 10 subscales. A higher score indicates a lower health status (28). In this study, the subscales of FIQ pain (0–100), FIQ anxiety (0–100) and FIQ depression (0–100) were used in addition to the FIQ total score.

Psychosocial factors. Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, Work (FABQwork) is a questionnaire that assesses how much fear and avoidance affect the work beliefs of patients with chronic pain on a scale from 0 to 42 (7 items). A higher score represents more fear avoidance beliefs about work (29).

Work-related factors. Physical Activity Index (PHYI) is a self-administered rating scale of physical activity at work, which includes 7 items that reflect manual materials handling including lifting, and is a workload index, ranging from 7 to 21.The instrument is validated and tested for reliability in a Swedish population (30).

Work status was assessed as work hours per week, as reported by the participants.

Perceived exertion at work is a numeric rating scale that ranges from 0 to 14, where a higher score represents a higher degree of physical exertion at work (30). It is a modified form of the Borg scale for ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) (31). This scale is the primary outcome of the study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), median (min–max), or n and percentage. Non-parametric tests were used for group comparisons and correlation analyses. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for analyses of between-group differences in continuous variables. The Mantel-Haenzel test was used for group comparisons in categorical variables. Between-group analyses were adjusted by logistic regression for the background variables that differed significantly between the 2 groups. The logistic regression specified group as dependent variable, the outcome of interest as main independent variable, and background variables as covariates. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to determine associations with perceived exertion at work in women with FM and healthy women, respectively, and associations between continuous variables in separate analyses of groups based on physical workload. The following classification was used to interpret the correlation values, given that p-values were less than 0.05: rs 0–0.25 indicates little or no relationship, rs 0.25–0.50 indicates a fair degree of relationship, rs 0.50–0.75 a moderate to good relationship, while a correlation above rs 0.75 indicates a very good to excellent relationship (32). Linear regression analysis was used to analyse explanatory factors for perceived exertion at work. Variables were included in the models in order of the strength of their correlations, to perceived exertion at work found in the correlation analyses. Only variables that correlated significantly with perceived exertion at work were included in the models. The number of variables included in each model was limited to the number of women in each group, by one variable per every 10 women. p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Ethics

The study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Stockholm. Written and oral informed consent was obtained from all participants.

RESULTS

The study population comprised 73 working women with FM (mean age 50.4 years (SD 9.3)) and 73 healthy women (mean age 50.7 years (SD 9.3)) matched by occupation and physical workload. There was no significant difference in age between the 2 groups (p = 0.79). The mean symptom duration of the women with FM was 9.4 years (SD 7.8) and the mean tender point count was 15.6 (SD 2.0) (Table I). The mean weekly hours of leisure-time physical activity (LTPAI) of the women with FM was 4.47 h (SD 3.64), which was significantly lower (p < 0.001) than that of the healthy women 7.36 h (SD 4.96). The educational level was significantly lower (p = 0.019) in the women with FM compared with the healthy women. The women with FM worked significantly fewer hours per week (p < 0.001) compared with the healthy women, due to sick leave or disability pension, which in practice can be regarded as extended sick leave (Table I).

|

Table I. Characteristics of the study population, including women with fibromyalgia (FM) and healthy women |

|||

|

Characteristics |

Women with FM (n = 73) |

Healthy women (n = 73) |

p-value |

|

Symptom duration, years, mean (SD) Median (range) |

9.4 (7.8) 8.0 (0.2–35) |

||

|

Tender points, mean (SD) Median (range) |

15.6 (2.0) 16 (11–18) |

||

|

Age, years, mean (SD) Median (range) |

50.4 (9.3) 51 (22–63) |

50.7 (9.3) 51 (21–63) |

0.79 |

|

Leisure-time physical activity, h, mean (SD) Median (range) |

4.5 (3.6) 3.0 (0–17) |

7.4 (5.0) 6.0 (0–23) |

< 0.001 |

|

Education, n (%) |

|||

|

< 9 years |

9 (12.3) |

7 (9.6) |

|

|

10–12 years |

32 (43.8) |

21 (28.8) |

|

|

> 12 years |

32 (43.9) |

44 (56.3) |

0.019 |

|

Work status, n (%) |

|

||

|

20–49% |

5 (6.8) |

1 (1.4) |

|

|

50% |

25 (34.2) |

2 (2.7) |

|

|

51–79% |

17 (23.3) |

8 (11.0) |

|

|

80–100% |

26 (35.6) |

62 (84.9) |

< 0.001 |

|

Sick leave/disability pension, n (%) |

|||

|

25% |

13 (17.8) |

0 (0) |

|

|

50% |

22 (30.1) |

0 (0) |

|

|

75% |

4 (5.5) |

0 (0) |

< 0.001 |

|

Missing: education (n = 1). Significant p-values are shown in bold. SD: standard deviation. |

|||

There was no significant difference in physical activity at work (PHYI) between the women with FM and the healthy women (Table II). However, perceived exertion at work was significantly higher in the women with FM compared with the healthy women (p = 0.002).

Physical capacity was significantly lower in the women with FM than in the healthy women, measured by hand-grip force (Grippit) (p < 0.001), upper-arm strength (Isobex) (p < 0.001), quadriceps muscle strength (Steve Strong) (p < 0.001), and walking distance (6MWT) (p < 0.001). Symptom scores were significantly higher in the women with FM than in the healthy women, in pain (FIQ pain) (p < 0.001), depression (FIQ depression) (p < 0.001), anxiety (FIQ anxiety) (p < 0.001), and disease-specific health status (FIQ total) (p < 0.001). The mean fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) was 12.23 (SD 10.1) in the women with FM. This questionnaire was, however, not applicable for healthy women, thus no comparison was made between groups. The significant differences persisted when adjusted for background variables that differed significantly between the groups (LTPAI, education, and work hours per week) (Table II).

|

Table II. Between-group analyses of work-related factors, physical capacity, symptoms, and psychosocial factors unadjusted and adjusted for leisure-time activity, education, and work status in women with fibromyalgia (FM) and in healthy women |

|||||||

|

Measures |

Women with FM (n = 73) |

Healthy women (n = 73) |

Unadjusted p-valuea |

Adjusted p-valueb |

|||

|

Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

||||

|

Perceived exertion at work (0–14) |

5.77 (3.27) |

6.0 (0.0–13.0) |

4.11 (2.71) |

3.0 (0.0–10.0) |

0.0022 |

0.0069 |

|

|

Physical activity at work (PHYI) (7–21) |

9.68 (2.70) |

9.0 (7.0–18.0) |

9.34 (2.99) |

8.0 (7.0–20.0) |

0.162 |

||

|

Hand-grip force (Grippit) (N) |

158.69 (64.27) |

165.0 (44.5–319.0) |

239.49 (49.52) |

239.5 (134.5–362.0) |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

|

|

Upper-arm strength (Isobex) (kg) |

12.35 (5.02) |

13.0 (2.3–23.8) |

19.99 (5.16) |

19.4 (7.1–31.9) |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

|

|

Quadriceps muscle strength (Steve Strong) (N) |

324.45 (103.91) |

316.5 (113.5–584.5) |

423.18 (79.88) |

423.0 (190.0–640.0) |

< 0.0001 |

0.0001 |

|

|

Walking distance (6MWT) (m) |

562.15 (67.66) |

566.0 (376.0–766.0) |

660.48 (65.58) |

660.0 (508.0–818.0) |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

|

|

Disease specific health status (FIQ total) (0–100) |

55.94 (14.56) |

56.4 (16.7–88.0) |

6.99 (9.34) |

3.4 (0.0–50.0) |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

|

|

Pain (FIQ pain) (0–100) |

58.07 (20.29) |

59.0 (8.0–98.0) |

4.20 (7.66) |

0.0 (0.0–36.0) |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

|

|

Depression (FIQ depression) (0–100) |

43.73 (30.39) |

44.0 (0.0–97.0) |

6.96 (14.15) |

2.0 (0.0–76.0) |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

|

|

Anxiety (FIQ anxiety) (0–100) |

54.49 (29.51) |

56.0 (0.0–100.0) |

9.27 (18.31) |

2.0 (0.0–76.0) |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

|

|

Fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) (0–42) |

12.23 (10.08) |

11.0 (0.0–42.0) |

|||||

|

aAnalysed by Mann-Whitney U test. bPerformed by logistic regression specifying group as dependent variable, the outcome of interest as main independent variable and leisure-time physical activity (h), education and work status as covariates. Missing values: FIQ total for healthy women (n = 2), FIQ pain for healthy women (n = 7), FIQ depression for healthy women (n = 4) and FIQ anxiety for healthy women (n = 4). Significant p-values are shown in bold. PHYI: Physical Activity Index; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; FABQwork: Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, Work; SD: standard deviation; 6MWT: 6-min walk test. |

|||||||

Factors associated with perceived exertion at work

FM group (n = 73). Physical activity at work (PHYI), physical workload, and fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) showed moderate to good correlations with perceived exertion at work (rs = 0.65, p < 0.001; rs = –0.54, p < 0.001; rs = 0.53, p < 0.001, respectively), while anxiety (FIQ anxiety) showed an extremely weak correlation with perceived exertion at work (rs = 0.26, p = 0.027) (Table III).

|

Table III. Associations between perceived exertion at work and work-related factors, physical capacity, symptoms, and psychosocial factors in women with fibromyalgia (FM) |

||||||||

|

Measures |

Total FM group (n = 73) |

FM in medium heavy work (n = 27) |

FM in light work (n = 44) |

|||||

|

rs |

p-value |

rs |

p-value |

rs |

p-value |

|||

|

Physical activity at work (PHYI) |

0.68 |

< 0.001 |

|

0.44 |

0.022 |

|

0.53 |

< 0.001 |

|

Hand-grip force (Grippit) |

0.15 |

0.207 |

–0.48 |

0.012 |

|

0.23 |

0.143 |

|

|

Upper-arm strength (Isobex) |

0.08 |

0.509 |

–0.33 |

0.095 |

0.27 |

0.080 |

||

|

Quadriceps muscle strength (Steve Strong) |

–0.16 |

0.166 |

0.06 |

0.782 |

0.23 |

0.138 |

||

|

6-min walk test (6MWT) |

–0.06 |

0.604 |

–0.15 |

0.455 |

0.04 |

0.779 |

||

|

Disease-specific health status (FIQ total) |

0.22 |

0.066 |

0.41 |

0.033 |

|

0.00 |

0.998 |

|

|

Pain (FIQ pain) |

0.15 |

0.195 |

0.44 |

0.020 |

|

–0.12 |

0.441 |

|

|

Depression (FIQ depression) |

0.12 |

0.301 |

0.33 |

0.097 |

0.07 |

0.654 |

||

|

Anxiety (FIQ anxiety) |

0.26 |

0.027 |

|

0.46 |

0.017 |

|

0.14 |

0.372 |

|

Fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) |

0.53 |

< 0.001 |

|

0.43 |

0.024 |

|

0.31 |

0.038 |

|

Age |

–0.14 |

0.250 |

–0.36 |

0.064 |

–0.08 |

0.622 |

||

|

Symptom duration |

0.08 |

0.521 |

0.02 |

0.935 |

0.08 |

0.616 |

||

|

Tender point count |

0.08 |

0.495 |

–0.05 |

0.813 |

0.17 |

0.281 |

||

|

Education |

–0.02 |

0.841 |

0.01 |

0.961 |

0.22 |

0.144 |

||

|

Work status |

–0.02 |

0.881 |

0.42 |

0.031 |

|

–0.02 |

0.908 |

|

|

Leisure time physical activity (LTPAI) |

0.20 |

0.100 |

0.19 |

0.358 |

0.11 |

0.483 |

||

|

Significant p-values are shown in bold. rs = Spearmans rho. PHYI: Physical Activity Index; FABQwork: Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire; Work; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; LTPAI: Leisure Time Physical Activity Instrument. |

||||||||

Healthy control group (n = 73). Only work-related factors correlated significantly with perceived exertion at work in the healthy women. PHYI and physical workload showed moderate to good correlations with perceived exertion at work (rs = 0.70, p < 0.001 and rs = –0.63, p < 0.001, respectively).

Sub-analysis of the FM group with a medium heavy physical workload (n = 27). Hand-grip force (Grippit) showed a fair correlation with perceived exertion at work (rs = –0.48, p = 0.012), as did anxiety (FIQ anxiety) (rs = 0.46, p = 0.017), pain (FIQ pain) (rs = 0.44, p = 0.020), physical activity at work (PHYI) (rs = 0.44, p = 0.022), fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) (rs = 0.43, p = 0.024), work status (rs = 0.42, p = 0.031), and disease-specific health status (FIQ total) (rs = 0.41, p = 0.033) (Table III).

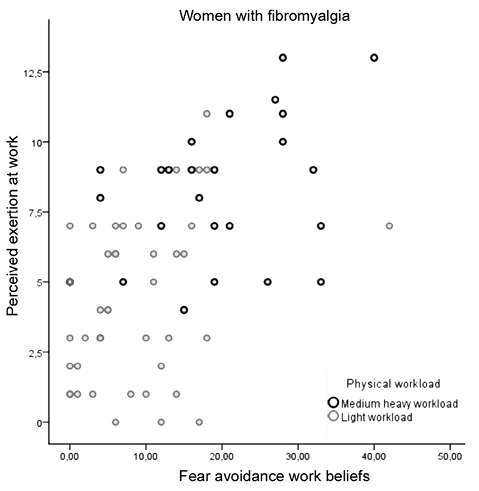

Sub-analysis of the FM group with a light physical workload (n = 44). PHYI showed a moderate to good correlation with perceived exertion at work (rs = 0.53, p < 0.001), while fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) showed a fair correlation with perceived exertion at work (rs = 0.31, p = 0.038) (Table III). However, there was an outlier that scored maximum fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork), which contributed to the significant correlation. When the outlier was omitted, the correlation was no longer significant (rs = 0.281, p = 0.068). Fig. 2 shows a plot of fear avoidance work beliefs and perceived exertion at work in women with FM.

Explanatory factors for perceived exertion at work in women with FM

FM group (n = 73). Factors included in the model were: PHYI, fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) and anxiety (FIQ anxiety). Physical activity at work (PHYI) and fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) were the only statistically significant variables to independently explain perceived exertion at work in the whole FM group, explaining 50% (Table IV).

Sub-analysis of the FM group with a medium heavy physical workload (n = 27). Due to the limited number of women in this group, the only factors included in the model were: hand-grip force (Grippit) and anxiety (FIQ anxiety). This model explained 34% of perceived exertion at work in the FM group with medium heavy physical workload (Table IV).

|

Table IV. Explanatory factors for perceived exertion at work in fibromyalgia (FM) |

||||

|

Explanatory factors for perceived exertion at work |

Adjusted R square |

Unstandardized coefficients |

p-value |

|

|

B |

Standard error |

|||

|

Total FM group (n = 73) |

||||

|

Model 1. Physical activity at work (PHYI) |

0.410 |

0.630 |

0.109 |

< 0.001 |

|

Model 2. Physical activity at work (PHYI) and fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) |

0.502 |

0.110 |

0.029 |

< 0.001 |

|

FM in medium heavy work (n = 27) |

||||

|

Model 1. Hand-grip force (Grippit) |

0.212 |

–0.016 |

0.006 |

0.010 |

|

Model 2. Hand-grip force (Grippit) and anxiety (FIQ anxiety) |

0.336 |

0.038 |

0.016 |

0.026 |

|

FM in light work (n = 44) |

||||

|

Model 1. Physical activity at work (PHYI) |

0.285 |

1.088 |

0.255 |

< 0.001 |

|

Significant p-values are shown in bold. PHYI: Physical Activity Index; FABQwork: Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, Work; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire. |

||||

Sub-analysis of the FM group with a light physical workload (n = 44). The only factor included in the model was PHYI, since the significant correlation between fear avoidance work beliefs (FABQwork) and perceived exertion at work disappeared once a single outlier was omitted from the analysis. Physical activity at work (PHYI) explained 29% of perceived exertion at work in the FM group with a light physical workload (Table IV).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was that perceived exertion at work was markedly higher in the women with FM than in the healthy women, matched by occupation and physical workload. A reason for this difference between the patient group and the healthy group might be the fact that the women with FM displayed significantly impaired physical capacity compared with healthy women. Physical capacity in FM was most impaired in the upper extremities, with a hand-grip force of 66% and an upper-arm strength of 62% compared with healthy women. In the lower extremities, the quadriceps strength was 75% of the strength in healthy women, and the walking distance was 85% compared with the healthy women. These results are in agreement with previous reports showing impaired physical capacity in FM varying from 20% to 54% compared with healthy controls (33–35).

The work-related factors of physical workload and physical activity at work showed the highest correlations with perceived exertion at work, both in women with FM and in healthy controls. Furthermore, physical activity at work, describing how much or little the person lifted, carried and moved around at work, was the strongest explanatory factor for perceived exertion at work for the total FM group and the only explanatory factor for perceived exertion at work in the FM group with a light physical workload. Thus, regardless of disease or health, these work-related factors are central for the experience of exertion at work, and for the ability to work, as reported previously (19, 23). These results are also in agreement with previous studies suggesting that adjustment of work tasks to the capacity of the individual would promote continued work in FM (36) and that less strenuous work demands are expected to promote work ability in FM (37).

Only work-related factors were associated with perceived exertion at work in the healthy women, while physical capacity, pain and distress did not show any correlation. This indicates that the healthy women had sufficient capacity for their work tasks and that their ability to work was associated with work-related factors only.

Hand-grip force and anxiety were the strongest explanatory factors for perceived exertion at work in the FM group with a medium heavy physical workload. The results indicate that hand-grip force is a critical factor for perceived exertion at work, and for work ability in this group. The results support previous findings that show strong associations between hand-grip force and work capacity in women with rheumatoid arthritis (38) and associations between symptom severity and perceived exertion at work in FM (15). The results of this study imply that women with FM with a medium heavy physical workload might be exposed to physical demands exceeding their physical capacity, which has been reported earlier to be a risk factor for work disability in musculoskeletal pain conditions (19, 23). The explanatory factor of anxiety for perceived exertion at work could be an indication that these women worry about their future work ability, and the risk of not managing work in the long term, which could lead to economic instability, isolation, and loss of part of their identity (37). For women with FM with a medium heavy physical workload, an improvement in muscle function, and especially hand-grip force, would probably enhance their ability to perform their strenuous work tasks and increase their chances of a sustainable work life. This perspective opens new opportunities for choice of treatment for this group and further studies are needed to explore whether an improvement in physical capacity would increase work ability in women with FM with physically strenuous work.

The fear of future sick leave, mentioned above, might also partly account for fear avoidance work beliefs being an explanatory factor for perceived exertion at work in the total FM group. Physical demands at work might increase the fear of physical overload from work and of not managing in the long term, which might lead to strategies of avoiding physical overload at work (37). The development of strategies for handling the physical demands at work would probably minimize anxiety and fear avoidance work beliefs and promote future work ability.

Pain was not a critical factor for perceived exertion at work since it was not found to be an explanatory factor. However, pain is an underlying factor for anxiety, fear avoidance, and impaired physical capacity in FM (39, 40). Such possible interactions between subjective and objective findings require further investigation.

The study population was classified by their physical workload in the analysis of explanatory factors for perceived exertion at work. A moderate correlation (rs 0.695, p < 0.001) between categories and reported PHYI supports the relevance of the chosen model of classification. Furthermore, the moderate correlations between perceived exertion at work and reported PHYI indicate that perceived exertion at work in women with FM adequately reflects the level of physical activity at work and lends validity for using the PHYI in future studies of women with FM.

There were no women with FM in the study population who had a heavy or heavy repetitive physical workload, while 60% of the women with FM had a light physical workload, 37% had a medium heavy physical workload, and 3% had a light repetitive physical workload. It is possible that women with FM who undertake heavy manual labour are scarce due to long-term sick leave or disability pension, which has been suggested in previous studies (6, 19, 20). More than half of the women with FM in the study population (53%) were on part-time sick leave or disability pension. Women with FM who have a heavier physical workload might be at a higher risk for sick leave, and a dose-response relationship between perceived exertion at work and long-term sick leave has been reported previously (21).

The women with FM had a significantly lower level of education than the healthy women, which could affect the perception of exertion at work, since a higher level of education often means having more control over one’s work situation and possibilities for more flexibility at work. However, when adjusted for differences in education, the significant difference of perceived exertion at work between groups remained, indicating that education was not a critical factor for the perception of exertion at work.

In conclusion, women with FM perceive an elevated exertion at work, which is associated with physical work-related factors and factors related to fear and anxiety. Perceived exertion at work in the women with FM was explained by their physical workload, physical activity at work, hand-grip force, anxiety, and fear avoidance work beliefs. Promotion of sustainable work ability in FM should include adjustments in work tasks to better match the capacity of the individual, and strategies for handling physical demands at work. Women with a medium heavy physical workload would benefit from improving their muscle function and strength to enhance their ability to perform strenuous work tasks and increase their chances of sustainable work ability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all their colleagues who performed examinations in Gothenburg, Alingsås, Linköping and Stockholm. The statistical advisors were Nils-Gunnar Pehrsson and Aldina Pivodic. The study was supported by the Swedish Rheumatism Association, the Swedish Research Council, the Health and Medical Care Executive Board of Västra Götaland Region, and ALF-LUA at Sahlgrenska University Hospital. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES