LONG-TERM FOLLOW-UP OF PATIENTS WITH MILD TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY: A MIXED-METHODS STUDY

Sara Åhman, MD1, Britt-Inger Saveman, RNT, PhD2, Johan Styrke, MD, PhD3, Ulf Björnstig, MD, PhD3 and Britt-Marie Stålnacke, MD, PhD1

From the 1Department of Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Rehabilitation Medicine, 2 Department of Nursing and 3Division of Surgery, Department of Surgical and Perioperative Sciences, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

OBJECTIVE: To characterize the long-term consequences of mild traumatic brain injury regarding post-concussion symptoms, post-traumatic stress, and quality of life; and to investigate differences between men and women.

DESIGN: Retrospective mixed-methods study.

Subjects/patients and methods: Of 214 patients with mild traumatic brain injury seeking acute care, 163 answered questionnaires concerning post-concussion symptoms (Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire; RPQ), post-traumatic stress (Impact of Event Scale; IES), and quality of life (Short Form Health Survey; SF-36) 3 years post-injury. A total of 21 patients underwent a medical examination in connection with the survey. The patients were contacted 11 years later, and 10 were interviewed. Interview data were analysed with content analysis.

RESULTS: The mean total RPQ score was 12.7 (standard deviation; SD 12.9); 10.5 (SD 11.9) for men and 15.9 (SD 13.8) for women (p = 0.006). The 5 most common symptoms were fatigue (53.4%), poor memory (52.5%), headache (50.9%), frustration (47.9%) and depression (47.2%). The mean total IES score was 9.6 (SD 12.9) 7.1 (SD 10.3) for men and 13.0 (SD 15.2) for women (p = 0.004). In general, the studied population had low scores on the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). The interviews revealed that some patients still had disabling post-concussion symptoms and consequences in many areas of life 11 years after the injury event.

CONCLUSION: Long-term consequences were present for approximately 50% of the patients 3 years after mild traumatic brain injury and were also reported 11 years after mild traumatic brain injury. This needs to be taken into account by healthcare professionals and society in general when dealing with people who have undergone mild traumatic brain injury.

Key words: traumatic brain injury; brain concussion; post-concussion symptoms; post-traumatic stress disorder.

J Rehabil Med 2013; 45: 795–801

Correspondence address: Britt-Marie Stålnacke, Department of Community Medicine and Rehabilitation (Rehabilitation Medicine) Bldg 9A, Umeå University Hospital, Umeå University, SE-901 85 Umeå, Sweden. E-mail: brittmarie.stalnacke@rehabmed.umu.se

Accepted April 23, 2013

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) are a major health problem worldwide. Mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) is by far the most common, representing 70–90% of all TBIs. The incidence of MTBI is between 100–300/100,000 inhabitants/year (1). The natural course after MTBI is resolution of symptoms within 3 months, which is the outcome for the majority of patients (2–4). However, a considerable proportion of patients (~7–45%) experience post-concussion symptoms for a prolonged period after the injury (5–7). These symptoms may include headache, dizziness, fatigue, irritability, poor memory, concentration difficulties, and depression. Although MTBIs are more prevalent among men than women (1), it has been shown that more women than men experience post-concussion symptoms and complications. In addition, female sex is suggested as one of several risk factors for prolonged symptoms (8–10). Other prognostic factors for persistent symptoms after MTBI are litigation/compensation-seeking, prior head injuries, psychiatric problems, and age over 40 years (11). Furthermore, the prevalence of MTBI is highest among young adults (1). Since they are more likely to be in the process of completing education and entering the labour market, the injury may have serious consequences for their work and future. Several studies have shown that post-concussion symptoms can decrease working ability and negatively affect leisure-time and social life (6, 12).

Following traumatic experiences such as MTBI, psychological disturbances, such as post-traumatic stress-related symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), can occur. Diagnosis of PTSD comprises a combination of intrusive, avoidance, and arousal symptoms. In a study conducted 6 months after MTBI, it was found that 20% of patients had developed PTSD (13), whereas another study reported that 10% of patients exhibited 3 or more post-traumatic stress-related symptoms 1 year after MTBI (14). The quality of life of people who have experienced MTBI may further decrease (15).

Many studies of post-concussion symptoms and complications after MTBI have follow-ups of 3 months, 6 months, or 1 year (4, 12, 16–20). However, fewer studies have investigated the long-term effects and consequences several years after MTBI (21–24). Self-perceived limitations in psychosocial function with low levels of life satisfaction have been reported in patients 3 years after MTBI (21). It has been shown that MTBI patients report significantly more post-concussion symptoms than control subjects 5–7 years after the injury (22). MTBI can further result in sequelae that significantly reduce quality of life, even 10 years later (23). In a follow-up study, patients with MTBI were evaluated 10 years after participating in a rehabilitation programme, and life satisfaction had decreased in the intervention group, but not among the controls (24).

Most studies on MTBI have used a quantitative design with validated questionnaires. Only a minority of studies have used a qualitative approach. A metasynthesis of 23 different qualitative studies has been published as a review (25). Collectively, these studies represent the views of 263 persons with mild to very severe TBI, ranging in age from 17 to 60 years. The main summary of the available research was the expression of a deep sense of loss associated with TBI. Key issues highlighted for persons who had survived TBI were loss and reconstruction of personal identity, loss of connection with, and control of, one’s body, emotional sequelae following injury, and loss and reconstruction of one’s place in the world.

Because there have been few long-term follow-up or qualitative studies of the consequences of MTBI, the aims of the present study were: (i) to follow up persons 3 years after MTBI regarding post-concussion symptoms, post-traumatic stress, and quality of life, and regarding differences between men and women; and (ii) to determine the long-term consequences for an individual level 11 years after MTBI.

METHODS

Patients and data

The baseline data originates from Umeå University Hospital’s injury database. Since 1985, all cases of injury from the defined population of Umeå have been registered upon arrival at the emergency department (ED). Our data-set was derived from the database from 2001, when 137,000 inhabitants lived in Umeå University Hospital’s catchment area. Inclusion criteria were: patients with a MTBI, which led to any degree of disturbed consciousness, amnesia, neurological deficit, severe headache, nausea, or vomiting, and who also arrived at the ED within 24 h of the brain injury. The severity of the TBI was classified according to the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (26) at the time of arrival at the ED. GCS 13–15 represents MTBI. A more thorough description of the registration procedure for this study has been published (27).

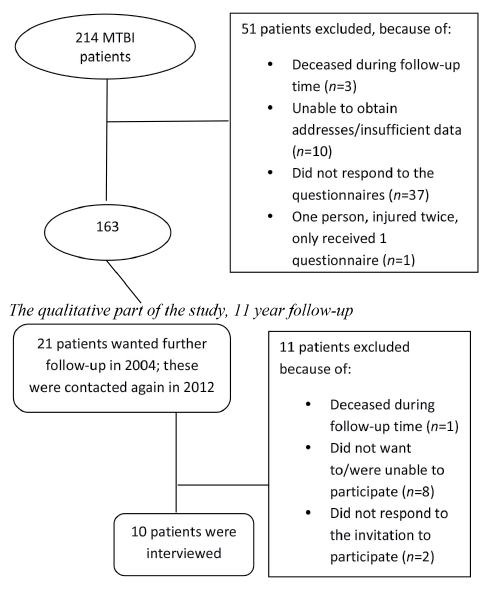

Follow-ups were conducted by questionnaire in 2004 and by interview in 2012. Of 214 MTBI patients who, in 2001, sought care within 24 h of injury at the ED of Umeå University Hospital, 200 aged 18–64 years were contacted 3 years post-injury. Altogether, as shown in Fig. 1, 163 individuals (81%) (68 women and 95 men) responded. Demographic variables are shown in Table I. Responders were compared with non-responders. No significant differences in proportions were found between responders and non-responders with the exceptions that alcohol inebriation at time of the injury was more common among the non-responders (p = 0.019) and that loss of consciousness was more common among the responders (p = 0.009). All persons participating in the follow-up study in 2004 answered a question regarding their wish for further follow-up, giving 21 positive responses. They all had a medical examination in connection with the survey, and some were referred for additional investigation or treatment. As a group, these patients rated their symptoms according to the RPQ as significantly more severe than the rest of the patients (p < 0.001). They also had higher total scores on the IES (p < 0.001). For the qualitative part of the present study, these persons were again contacted. Of those, 10 gave their informed consent and were assured of anonymity and confidentiality. Six were women and 4 were men, ranging in age from 31 to 70 years. Four were injured by falls, 3 in vehicle-related injury events, 1 by horse-back riding, and 2 by other causes. Eleven years after the injury, 3 persons were on sick leave, and 1 was receiving disability pension. They were interviewed and answered the same questionnaires as in 2004. Fig. 1 illustrates the process of inclusion to the study, and Table II the subjects’ demographics.

|

Table I. Demographic and injury characteristics |

|

|

Characteristics |

|

|

Gender, n (%) Male Female Age, years, mean (SD) |

95 (58.3) 68 (41.7) 30.8 (14.3) |

|

Education, n (%) 9 years 10–12 years 13–21 years |

19 (11.7) 90 (55.2) 54 (33.1) |

|

Previous head trauma, n (%) Yes, once Yes, more than once No Unknown |

44 (27.0) 24 (14.7) 79 (48.5) 16 (9.8) |

|

Cause of injury, n (%) Indoors fall Outdoors fall Falls from height Bicycle Horseback riding Assault Vehicle-related Sports-related Other |

16 (9.8) 33 (20.3) 10 (6.1) 25 (15.3) 5 (3.1) 9 (5.5) 37 (22.7) 23 (14.1) 5 (3.1) |

|

SD: standard deviation. |

|

Fig. 1. Process for inclusion of patients in the 3-year and 11-year follow-ups.

|

Table II. Demographic and injury characteristics for the qualitative part of the study |

|||

|

Patient |

Gender/ age, years |

Cause of injury |

Current occupation |

|

1 |

F/70 |

Outdoor fall |

Retired |

|

2 |

F/36 |

Fall from height |

Sick leave |

|

3 |

M/49 |

Other |

Sick leave |

|

4 |

F/64 |

Indoor fall |

Government employee |

|

5 |

M/59 |

Other |

Farmer |

|

6 |

M/67 |

Fall from height |

Retired |

|

7 |

F/34 |

Horseback riding |

Sick leave |

|

8 |

F/34 |

Vehicle-related |

Teacher |

|

9 |

M/31 |

Vehicle-related |

Lorry driver |

|

10 |

F/48 |

Vehicle-related |

Disability-pension |

|

F: female; M: male. |

|||

Questionnaires

The Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ) is a self-report symptom questionnaire consisting of 16 common symptoms following MTBI (7). The patients rate symptoms by degree of severity, on a scale of 0–4. The total RPQ score is the sum of the 16 ratings. Possible scores are 0–64. In this study, scores 1–4 were equivalent to having the symptom.

The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) is an instrument developed to measure physical and mental health and quality of life. It consists of 36 questions and measures 8 health domains. For each domain the possible score is 0–100, where higher scores indicate better health. For comparison, there are age- and gender-matched control groups (28).

The Impact of Event Scale (IES) is a self-report questionnaire developed to measure anxiety and stress-reactions resulting from a specific event. The total score can vary from 0 to 75 and can be divided into 4 grades of stress reactions: sub-clinical (0–8), mild (9–25), moderate (26–43) and severe (44–75). The scale also provides ratings of avoidance and intrusion (29).

The questionnaires also contained questions about education levels and previous head trauma.

Qualitative interviews

Data were collected with semi-structured interviews. An interview guide was used during the interviews, making sure that the following areas were covered: thoughts about the injury event and the time immediately following the MTBI, general well-being and limitations in everyday life after the injury event, changes in occupational and family situation after the incident, and thoughts and feelings about the future. The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim.

The interviews were analysed using qualitative content analysis (30). The interviews were read and the text extracted to meaning units. The meaning units were condensed and coded, then divided into categories and subcategories. During the process, which went back and forth between the text (meaning units) and the emerging categories to ensure internal validity, the first author and two others continuously discussed and reached a consensus on the final categories and subcategories.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of Umeå University, Sweden (number 04-097M and 2012-48-32M).

Statistics

All statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 18.0.0. Data are mean values (standard deviations; SD) unless otherwise indicated. As some samples were rather small and/or not normally distributed, a statistical evaluation was performed with non-parametric tests. Thus, Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison between responders and non-responders, and for comparison between participants in the further follow-up and those who participated in the follow-up only through questionnaires. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare individual questionnaire scores from 2004 and 2012. Gender comparisons were made by χ2 test and Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Symptoms and their severity 3 years after MTBI

Three years after MTBI, the RPQ total score was 12.7 (SD 12.9). For men, the total score was 10.5 (SD 11.9), and for women 15.9 (SD 13.8) (p = 0.006). The 5 most commonly found symptoms among the patients were fatigue (53.4%), poor memory (52.5%), headache (50.9%), frustration (47.9%), and depression (47.2%). Women reported a significantly higher prevalence of headaches (60.3%) and depression (47.2%) in comparison with men (44.2%, 47.2%, p = 0.043 and p = 0.029, respectively). The mean severity score of the 5 most disturbing symptoms of the RPQ is shown in Table III. Women reported significantly more problems than men with all symptoms, except poor memory and sleep disturbance.

|

Table III. Mean severity of the 5 most disturbing symptoms according to the Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ) |

||||

|

Symptom |

Total Mean (SD) |

Men Mean (SD) |

Women Mean (SD) |

p-value |

|

Fatigue |

1.2 (1.3) |

1.0 (1.2) |

1.5 (1.5) |

0.013 |

|

Headache |

1.1 (1.3) |

0.9 (1.2) |

1.4 (1.4) |

0.006 |

|

Poor memory |

1.1 (1.3) |

1.0 (1.2) |

1.2 (1.4) |

0.326 |

|

Depression |

1.0 (1.3) |

0.8 (1.2) |

1.3 (1.4) |

0.012 |

|

Sleep disturbance |

1.0 (1.4) |

0.9 (1.3) |

1.3 (1.5) |

0.082 |

|

SD: standard deviation. |

||||

Post-traumatic stress

The mean total stress score on the IES was 9.6 (SD 12.9). Women reported significantly higher scores (13.0; SD 15.2) in comparison with men (7.1; SD 10; p = 0.004).) Of all the patients, 65.4% had intrusion symptoms and 59.5% had avoidance symptoms. There were no significant differences between men and women regarding the prevalence of intrusion and avoidance symptoms. The mean intrusion score was 4.5 (SD 6.2). For men it was 3.2 (SD 4.7) and for women 6.2 (SD 7.5) (p = 0.002). The mean avoidance score was 5.0 (SD 7.7). For men it was 3.8 (SD 7.0) and for women 6.6 (SD 8.5) (p = 0.024). Regarding post-traumatic stress grades, moderate to severe stress was reported by 10% of men and 14% of women.

Quality of life

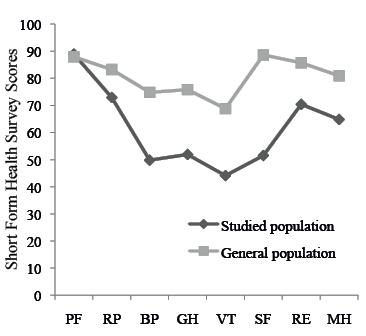

The scores for the 8 different scales of the SF-36 are shown in Table IV. Women had significantly lower scores than men in Role Physical, Role Emotional, and Mental Health (p = 0.049, 0.002 and 0.025). The scores in the studied patient material were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than in the Swedish general population (n = 8930) in all of the 8 domains in SF-36, except Physical Functioning (31) (Fig. 2).

|

Table IV. Mean scores in the 8 different domains of the SF-36. Data represent mean (standard deviation) |

||||

|

SF-36 domain |

All (n = 163) Mean (SD) |

Men (n = 95) Mean (SD) |

Women (n = 68) Mean (SD) |

p-value |

|

PF |

88.9 (18.7) |

89.9 (17.8) |

87.6 (19.9) |

0.442 |

|

RP |

72.9 (38.7) |

77.9 (35.1) |

65.8 (42.5) |

0.049 |

|

BP |

49.8 (17.2) |

49.2 (16.8) |

50.6 (17.9) |

0.616 |

|

GH |

51.9 (16.1) |

51.3 (15.4) |

52.7 (17.1) |

0.585 |

|

VT |

44.1 (17.3) |

45.6 (17.1) |

42.0 (17.5) |

0.199 |

|

SF |

51.5 (8.6) |

51.6 (8.5) |

51.3 (8.7) |

0.780 |

|

RE |

70.4 (40.3) |

78.5 (34.4) |

59.2 (45.3) |

0.002 |

|

MH |

64.8 (9.4) |

66.1 (9.4) |

62.8 (9.0) |

0.025 |

|

SD: standard deviation; PF: physical functioning; RP: role physical; BP: bodily pain; GH: general health; VT: vitality; SF: social functioning; RE: role emotional; MH; mental health. |

||||

Fig. 2. Studied population’s scores on the Short Form Health Survey compared with general Swedish population’s scores. PF: physical functioning; RP: role physical; BP: bodily pain; GH: general health; VT: vitality; SF: social functioning; RE: role emotional; MH: mental health.

Symptoms, post-traumatic stress, and quality of life 11 years after the injury

In the small group of interviewed persons there were no statistically significant differences 11 years after the MTBI in comparison with 3 years after the injury on the total RPQ (from 27.7 (SD 20.3) to 24.3 (SD 19.7); p = 0.123), the total IES score (from 30.3 (SD 18.6) to 25.2 (SD 20.6); p = 0.241), and on all domains on the SF-36.

Experiences 11 years after MTBI

The patients described a spectrum of life situations, and 3 distinct groups of patients emerged. There were patients who had never given the injury event leading to MTBI any thought. These patients had no complications after the injury, but were positive to follow-up. On the other hand, there were patients whose lives were altered by the MTBI and were disabled to some degree by it; physically or mentally, or both. A third group of patients had developed other diseases during the 11 years since the MTBI, and were disabled because of them. These 3 patient groups contributed to the developed categories and subcategories found during the analysis process, as shown in Table V.

|

Table V. Categories and subcategories |

||

|

Personal consequences |

Social consequences |

Dealing with the injury today |

|

Physical limitations |

Effects on work life |

Thoughts about the injury event |

|

Mental effects |

Effects on family life |

Thoughts about the time after the injury event |

|

Cognitive limitations |

Effects on social life |

Thoughts about the future |

The first category, “Personal consequences” of the injury event was, to a large extent, physical and mental limitations. There were patients who described physical limitations immediately after the injury event, such as exhaustion, debilitation, dizziness, severe headache, and neck pain. The mental limitations described included nervousness and fear.

“It was unpleasant, I had a terrible headache.”

“Pain. Nervous, I was afraid.”

Shortly after the injury event, and continuing to the present, patients described many remaining physical and mental consequences. They were commonly tired and had sleep disturbances. The fatigue was described as both physical and mental. The term “lack of energy” was also specifically used. Pain was also frequently described, both directly after the injury event and in the present.

“I want so much more than I feel I am capable of, that’s what has been tough.”

“I don’t know if it comes from the neck, but I’ve got more headache too.”

The mental limitations stemming from the injury event and its complications were described as emotions, such as anger and irritation. The patients, furthermore, described fear of things that they associated with the injury event; for example, travelling by bus or watching television programmes where cars were driven at high speeds. Aside from the negative feelings, there was also a search for some positive consequences of the injury.

“Well, you’re pissed off the day it happened, I still am.”

“There’s nothing bad that doesn’t bring something good with it; maybe it stopped me from working as I did.”

Cognitive limitations were expressed in terms of having impaired memory, difficulties concentrating and becoming easily stressed and irritable. The important role of scheduling daily life was highlighted.

“I have a hard time remembering things. I get annoyed easily. I just want to be alone sometimes. Have difficulties concentrating. If I’m going anywhere I’m really stressed out.”

Some patients had impaired memory, were bothered by fatigue, or had other physical, mental or cognitive problems, which they had never directly connected with the injury event. They still believed that it was possible that the injury could be the cause of their problems, but other factors, such as ageing, were also considered.

“Well, I don’t have any limitations from that brain injury. I get dizzy easily, but that could be for some other reason… I don’t know.”

The second category was comprised of consequences for work life, family life, and social life. In a broader context, social life included thoughts and perceptions about healthcare. Work performance consequences were described, and it was found that some patients were still on sick leave and did not think they could return to work. Others had been on sick leave and were returning to work. For some patients, the injury event never affected their work.

“I’m still sick, I’m on sick leave. I haven’t gotten over it.”

“I feel that I want to go back to my old job, but I feel, I don’t think I’m going to make it.”

Participants also described effects on family life. The patients sometimes felt that demands from family and friends were greater than what they could achieve or manage, both in terms of housework and in relationships with others. They also thought that the consequences of the injury event affected their family members and that the whole situation was difficult for the family. On the other hand, some experienced no effects on the same areas of life.

“You have your hands full only being a family father when you’re home with the kids and there – you’re sometimes not enough either.”

Socially, the patients had a sense of alienation because of the effects of MTBI. This was described as feeling worthless or abnormal because of limited energy compared with healthy people or because of sick leave and not being able to have a job. People also experienced an uncomprehending society, and felt that people might begin to gossip if they related their difficulties.

“Just being understood, that’s what I think is the hardest part in everyday life.”

“Then you have to deal with the children; why aren’t you working mom? You have to work like everybody else, and yes of course I have to be like all the other moms.”

Thoughts about healthcare were dichotomized. Participation in a rehabilitation programme was described as positive and as having helped lead to improvement. However, it also gave a patient stigma, contributing to a feeling of alienation and abnormality in society. Some patients wished that all the physical consequences of the injury event had been examined properly from the beginning. Gratitude was also expressed for healthcare, and patients said that, without healthcare, return to an acceptable life would have been much more difficult.

“I’ve been very lucky to meet understanding persons because I don’t think it is that known, brain tiredness, as you think it is; it isn’t.”

“Nobody prepared me for the fact that I was going to have cognitive difficulties or I mean brain tiredness, what’s that?”

The third category, “Dealing with the injury today” showed great diversity concerning thoughts about the past. Some of the patients, as previously mentioned, had never given the injury event any thought. Others described a drastic change between life before and after the injury because of physical, mental and cognitive limitations.

“I haven’t thought about the brain injury, I have many other things to think about instead.”

“It was drastic, you just wanted to bury your head in the sand, let it all blow over.”

Overall, the patients’ prevailing thoughts about the future were positive or indifferent. The central attitude was to take one day at a time and to avoid thinking too much about the future. Strategies for coping with the consequences of MTBI mainly involved avoiding pondering about the future too much and learning how to live with the consequences of the injury event. Another strategy was for subjects to try to do the things they wanted to do on those days when energy and motivation were present. Drugs, such as analgesics and antidepressants, also made life easier, or acceptable, for some.

“I just take 1 day at a time because in my life now, anything could happen, you can’t chew on that. You have to look forward.”

“Well, it has been tough, but thanks to medication I’ve been able to find, like a balance in everyday life between activity and rest and so.”

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study were that symptoms and consequences of MTBI may still be present both 3 and 11 years after the injury event. During the process of interviewing patients 11 years after the injury event, it became clear that symptoms and disabilities continued for some of the patients. They experienced physical, mental, and cognitive limitations as well as the feeling of alienation and lack of societal understanding. On the other hand, several of the MTBI patients had fully recovered.

In the present study, fatigue was the most common symptom 3 years after MTBI. This finding is in accordance with previous studies shortly after the injury (4, 15, 17, 20). Fatigue has also been reported as the most common symptom 10 years after MTBI (23). It seems that fatigue is the most frequent persistent symptom, both early and late after a MTBI. During the interviews with patients 11 years after injury, it was also stated that fatigue, both mental and physical, was one of the major difficulties in everyday life. Fatigue was described as a road-block affecting daily life, forcing the patients to plan all their activities. Mental fatigue after MTBI is a well-known phenomenon, and studies show that severe fatigue is highly associated with limitations in daily functioning and lower levels of life satisfaction (32). This was also illustrated clearly by the interviewed patients. Headache and poor memory were also among the most frequent symptoms reported by the patients 3 years after the injury. This is in accordance with previous research (17, 20), and it is possible that these symptoms are connected with fatigue. It seems likely that having headaches for longer periods could lead to fatigue. Fatigue may also contribute to cognitive symptoms, e.g. poor memory.

The 5 most disturbing symptoms, reported after 3 years, differed from the 5 most common symptoms. Although frustration was more common, sleep disturbance was more of an issue. It seems reasonable to assume that there was a relationship between sleep disturbances and fatigue.

In a previous study, which also used the RPQ to measure post-concussion symptoms after MTBI (33), 1 year after the injury a total RPQ score of 15.1 was reported. Because our results were in the same range, this could suggest that not much changes in terms of post-concussion symptoms between 1 and 3 years after MTBI. The symptoms persist, although slightly less frequently.

A minority of the patients had scores on the IES corresponding to moderate or severe post-traumatic stress reaction. This finding is consistent with the results from another study in which the IES was used 1 year after MTBI (14). Nevertheless, in some previous studies, patients with MTBI were examined for PTSD, and 17–20% of the studied patients met criteria for PTSD at 6 months after the injury (13, 34).

The present findings suggest that post-traumatic stress-related symptoms were not much of a problem for the patients 3 years after MTBI, although a substantial part of the patients may have had post-traumatic stress closer to the injury date. In a previous study of the same patient population the presence of post-concussion symptoms was shown to correlate with low levels of life satisfaction (21). This relationship is in accordance with a previous Swedish study conducted 3 months and 1 year post-injury (35).

In the present study, quality of life was compared between the subjects and the average population. Because patients reported significantly lower scores on all domains of the SF-36, these findings indicate that MTBI can result in sequelae that significantly reduce quality of life.

The majority of persons who answered the questionnaires in 2004 were men, but, in agreement with previous research (9), the women demonstrated more symptoms and, at more severe levels, higher grades of post-traumatic stress, and lower grades of life satisfaction.

In the qualitative part of the study, it was obvious that the patients whose symptoms or difficulties continued felt alienated by society. These feelings manifested because of patient limitations and because other people often did not understand their problems. Our findings regarding the patients’ feelings of alienation are in accordance with previous research (36). In order to address this problem, more public education about MTBI and its long-term symptoms and limitations are required. For some patients the symptoms and consequences of the injury event continued to affect areas such as family life and work. In line with previous research (37), patients in the present study had to restructure their lives and adapt to their current situation.

Previous studies have shown that people with TBI of all grades experience a sense of loss of self, and a void, which is filled by the patients reconstructing stories about the injury and the recovery (25, 38, 39). Although we only included MTBI, some patients reported similar feelings. These experiences were demonstrated more frequently among the group with persistent symptoms.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. There was no control group, although that would have been illustrative. Post-concussion symptoms were commonly reported, but these symptoms are not exclusively encountered after MTBI, as they are also reported in the general population (40). On the other hand, the strength of this study is that it is based on one year of material from an injury database; hence it is genuinely epidemiological and representative for people with MTBI in a well-defined population and geographical area. The response rate was high, at 81%, and the questionnaires that were used in the study are validated and have often been used with persons with MTBI. Of the 21 patients who participated in the further follow-up with medical examination, 10 were included in the qualitative study 11 years after the injury. Because these patients belonged to the group with significantly more symptoms than the other 3 years after the injury, they seem to be representative of patients with more problems after the injury.

The process of interviewing patients and comparing their answers with the questionnaires elucidated a notable divergence between some of the patients’ own stories and how they answered the questionnaires. The questionnaires did not give a fair picture of their life situations and difficulties. Their life stories gave an image of a troubled life. However, from the answers to the questionnaires, their lives did not seem to be so troubled. This difference could have had varying causes. It may have been that, due to cognitive impairment, they were unable to answer the questionnaires adequately, implying that information may be lost when conducting research on symptoms and personal difficulties in a quantitative manner with questionnaires. Another interpretation might be that commonly used instruments, such as the SF-36, even with a large number of questions, might not provide a true picture of an individual’s experiences.

In conformity with other studies performed many years after the injury event, it can be difficult to separate consequences following the MTBI from consequences following more recent events in life, the so-called “black box”. During 3 (and even more in 11) years, many things could have happened that affected the answers on the different questionnaires. Insecurity is inevitable when carrying out long-term follow-ups. Interviews are a good complement to questionnaires when opening the black box and seeing its contents. Interviews are also a way of listening to the patient’s voices in clinical research.

Like other studies performed with interviews, the results are an interpretation of the research participants’ statements. In turn, the statements in the current study are the patients’ interpretations of their lived experiences. There may be more than one possible interpretation of the interview text. We argue, however, that due to thorough analysis of the text the present results are valid.

In conclusion, MTBI can result in long-term symptoms and disabling consequences. These are observed both 3 and 11 years after the injury event, as illustrated in this study by questionnaires and interviews. The long-term consequences of MTBI must be addressed by healthcare and society as real and possible issues, and it is important that resources and adequate knowledge exist to enable the identification of symptoms and proper treatment of affected individuals.

REFERENCES