Maria Wertli, MD1,3, Lucas M. Bachmann, MD, PhD1, Shira Schecter Weiner, PT, PhD, CIE3 and Florian Brunner, MD, PhD2

From the 1Horten Center for Patient Oriented Research and Knowledge Transfer, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Zurich, 2Department of Physical Medicine and Rheumatology, Balgrist University Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland and 3NYU Hospital for Joint Disease, Occupational and Industrial Orthopaedic Center (OIOC), New York University, New York, USA

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this systematic review was to merge and summarize the current evidence about prognostic factors relevant to the course of complex regional pain syndrome 1.

METHODS: MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO, CENTRAL and screened reference lists of included studies were searched for studies of parameters associated with the prognosis of the condition. Studies investigating stroke-related complex regional pain syndrome were excluded.

RESULTS: Searches retrieved 2,577 references, of which 12 articles were included in the study. The preferred diagnostic criteria were the Veldman and the International Association for the Study of Pain criteria. The mean level of study quality was insufficient. A total of 28 prognostic factors was identified. Sensory disturbances and cold skin temperature appear to represent parameters associated with poor prognosis in complex regional pain syndrome 1. For many parameters the evidence is contradictory.

CONCLUSION: Evidence about prognostic factors for complex regional pain syndrome 1 is scarce, which prevents firm conclusions being drawn. Further high-quality aetiological and clinical research is needed.

Key words: CRPS; complex regional pain syndrome; algodystrophy; prognosis; systematic review.

J Rehabil Med 2013; 45: 00–00

Guarantor’s address: Florian Brunner, Department of Physical Medicine and Rheumatology, Balgrist University Hospital, Forchstrasse 340, CH-8008 Zurich, Switzerland. E-mail: florian.brunner@balgrist.ch

Accepted Oct 4, 2012; Epub ahead of print Feb 6, 2013

INTRODUCTION

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type 1 is a syndrome with significant morbidity and loss of quality of life (1, 2). It usually appears after a noxious event, such as trauma or surgery (3), and the clinical manifestations include sensory, autonomic, motor and trophic changes (4). Despite increasing research into CRPS, the exact underlying mechanisms of this syndrome are unknown. In a recent review article, Marinus et al. (5) concluded that compelling evidence implicates biological pathways that underlie aberrant inflammation, vasomotor dysfunction, and maladaptive neuroplasticity in the clinical features of CRPS. In contrast to CRPS type 2, which is characterized by a definable nerve lesion, CRPS type 1, formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy or algodystrophy, appears without a definable nerve lesion (4).

Clinical experience suggests that every patient should be treated early and aggressively in the hope of preventing chronicity. Treatment is empirical and usually includes a multidisciplinary approach using a combination of pharmacological, physical, occupational and psychological therapies (6). However, clinical observation reveals that, in a substantial proportion of patients, resolution occurs spontaneously or the natural course is benign (7), sometimes even without treatment. However, on the other hand, a subgroup of patients with CRPS 1 will experience an unfavourable course of the disease, with consequent high healthcare costs. If this subgroup of patients could be identified at an early stage, i.e. with prognostic instruments, treatment activities could be focused and specifically tailored to fit the needs of these patients.

Until now, evidence regarding prognostic aspects of CRPS 1 has not been assessed systematically. The literature is scattered and not easy to access. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to merge and summarize the current evidence about prognostic factors relevant for the course of CRPS 1. For this study, prognostic factors were defined as all clinical and non-clinical parameters with relevant impact on clinical course and treatment response, reflected by persisting impairment, disease duration and long-term disability.

METHODS

Literature search

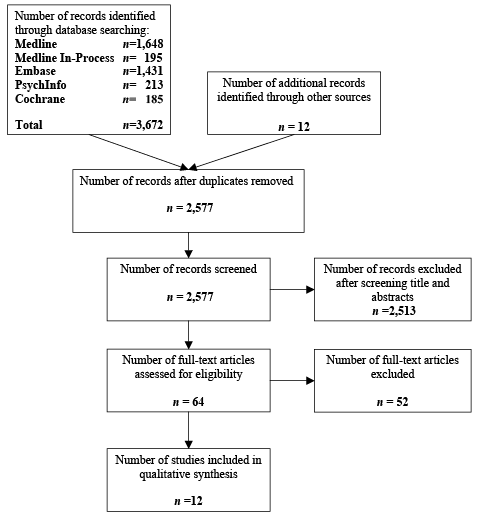

The search methodology was carried out according to the MOOSE statement (Fig. 1) on conducting a meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (8). All observational studies investigating prognostic factors of CRPS 1, published between 1990 and July 2011, were identified by searching the following databases: MEDLINE (OvidSP), MEDLINE In-Process Citations (OvidSP), Embase (OvidSP), Embase (OvidSP), PsychINFO and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). Searches were restricted to 1990 onwards, because the current definition of CRPS was introduced in the early 1990s (4). The search was conducted with the help of an experienced information specialist working in the field of systematic reviews. Search terms included, in addition to medical subject headings (MeSH terms), all commonly used terms for CRPS (e.g. complex regional pain syndrome(s), reflex sympathetic dystrophy, Sudeck’s atrophy, algodystrophy, shoulder hand syndrome). A detailed search strategy is depicted in Table I. To ensure the completeness of the literature search, the reviewers, experienced researchers in the field of CRPS, screened bibliographies of all included studies, retrieved review articles and current treatment guidelines in an additional hand search, and all (inclusion and exclusion criteria applied) potential studies were additionally included.

Fig. 1. Study flow.

|

Table I. Search strategy Medline (OvidSP) (1990–2011/07/wk 27) |

||

|

Search |

Results |

|

|

1 |

complex regional pain syndromes/ or reflex sympathetic dystrophy/ |

3,520 |

|

2 |

(CRPS 1 or CRPS or complex regional pain syndrome$ or RND).ti,ab. |

1,823 |

|

3 |

(reflex$ sympathetic dystroph$ or sudeck$ atroph$ or algodystroph$ or algoneurodystroph$).ti,ab. |

2,065 |

|

4 |

(algo dystroph$ or algo neurodystroph$).ti,ab. |

13 |

|

5 |

(shoulder hand syndrom$ or shoulder hand dystroph$).ti,ab. |

259 |

|

6 |

cervical sympathetic dystroph$.ti,ab. |

0 |

|

7 |

or/1–7 |

5,017 |

|

8 |

animals/ not (animals/ and humans/) |

10,061 |

|

9 |

8 not 9 |

5,015 |

|

10 |

prognosis/ or exp treatment outcome/ |

769,448 |

|

11 |

(outcome$ or predict$ or prognosis or recover$ or remission or relaps$ or deteriorat$ or exacerbat$ or worsen$ or course$).ti,ab. |

2,146,668 |

|

12 |

(Cure$ or curative$ or resolv$ or resolution$ or heal$ or improv$ or recuperat$).ti,ab. |

2,498,217 |

|

13 |

(convales$ or alleviat$ or decreas$ or lessen$).ti,ab. |

1,408,991 |

|

14 |

or/11–14 |

5,273,995 |

|

15 |

10 and 15 |

1,869 |

|

16 |

limit 16 to yr=“1990 –Current“ |

1,648 |

Study selection, data extraction and synthesis

The bibliographic details of all retrieved articles were stored in an Endnote file. Two reviewers (MW and FB) independently screened all references by title and abstract. We selected observational studies investigating prognostic parameters of CRPS 1. We did not apply any language restrictions. Studies investigating stroke-related CRPS 1 were excluded. All included references were independently reviewed in full text (MW and FB). During the screening and inclusion process all disagreements were discussed between the two reviewers and resolved by consensus. A designated third author (LMB) arbitrated any disagreement and facilitated consensus. Based on this review we extracted and catalogued all reported prognostic factors and data on salient clinical features. For any abstract where the full text was not available, the author was contacted.

Alternative researchers with specific language proficiencies were used for non-English language references. For descriptive purposes and to weight the included studies, study quality was assessed according to the proposed guidelines for assessing Quality in Prognostic Studies (9) in a two-step approach. Two reviewers (FB and MW) first individually compiled the fully operationalized, prognostic factors (correlation between the prognostic factor and the outcome). Secondly, these prognostic factor responses were tested for each of 6 potential biases: representative study population, drop out, adequate measurement of the prognostic factor, outcome measurement, confounding measurement and account, and analysis. Reviewers discussed the independent ratings and sought consensus about the overall risk of bias. A summary is reported in Table II. No quality score was used, as recommended by Hayden et al. (9). As the included studies did not allow a statistical synthesis of outcome measures, quality criteria were used for descriptive purposes only and not for exclusion criteria. Synthesis of quality was categorized as good (good for all 6 potential biases), acceptable (at least partly fulfilling all 6 criteria) and poor.

|

Table II. Methodological quality of the included studies |

|||||||

|

Author, years |

Study participation: study sample represents population of interest: yes, partly, no, unsure |

Study attrition: Loss to follow-up is not associated with key characteristics |

Prognostic factor measurement: prognostic factor of interest is adequately measured |

Outcome measurement: outcome of interest is adequately measured in study participants |

Confounding measurement and account: important potential confounders are appropriately accounted for? |

Analysis: statistical analysis is appropriate for the design of the study |

Synthesis of quality |

|

Bejja et al., 2005 (10) |

Unsure |

Unsure |

Yes |

Yes |

Unsure |

Yes |

Poor |

|

Dauty et al., 2001 (11) |

Partly |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Unsure |

Unsure |

Poor |

|

De Mos et al., 2009 (12) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Good |

|

Eulry et al., 1990 (13) |

Partly |

Yes |

Unsure |

Unsure |

Unsure |

No |

Poor |

|

Goris et al., 1990 (14) |

Yes |

Unsure |

Yes |

Yes |

Unsure |

Yes |

Poor |

|

Laulan et al., 1997 (15) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unsure |

Yes |

Poor |

|

Sandroni et al., 2003 (7) |

Partly |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Acceptable |

|

Tan et al., 2009 (16) |

Yes |

Yes |

Unsure |

Yes |

Unsure |

Yes |

Poor |

|

van der Laan et al., 1998 (17) |

Unsure |

No |

Unsure |

Yes |

Unsure |

Yes |

Poor |

|

Vaneker et al., 2005 (18) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Good |

|

Vaneker et al., 2006 (19) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Good |

|

Zyluk 1998 (20) |

Yes |

Unsure |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Poor |

RESULTS

Study selection

Fig. 1 shows the study selection process and agreement on study inclusion. Our search retrieved 2,577 records, from which 64 were identified for full review based on title and abstract. Full text assessment utilizing inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in the exclusion of 52 studies. The main reasons for exclusion were study design (clinical trials) and outcome measures (no prognostic factors investigated). In total, 12 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria (7, 10–20).

Study characteristics

The study characteristics are summarized in Table III. In total, 2,246 subjects (median number of subjects 74, range 16–1,006) were investigated. Symptom duration ranged from less than 3 months (11) to more than 8 years (18).

Four studies followed a prospective study design (11, 14, 15, 18). With the exception of 1 study (14), the prospective studies, included fewer patients (n = 16–47, mean 28) compared with those with a retrospective design (n = 42–199, mean 98).

Based on the quality assessment, quality was good in 4, acceptable in 1 and poor in 9 studies (Table III).

|

Table III. Characteristics of the included studies (n=12) |

||||||||||

|

Author, year |

Study design |

Diagnostic criteria |

Disease durationa |

Initiating event |

Location |

n (f/m) |

Age, yearsa |

Positive prognostic factors |

Negative prognostic factors |

Outcome |

|

Bejia et al., 2005 (10) |

Retrospective |

NR |

16.7 months (25.5) |

Traumatic, atraumatic |

UE, LE |

60 (40/20) |

51.6 [16–81] |

Spontaneous onset of CRPS |

Male gender Age < 40 years Cold skin temperature Initiating event Delayed diagnosis (> 2 months) |

Response to treatment (22) |

|

Dauty et al., 2001 (11) |

Prospective |

Veldman (21) |

35 days (10.2) |

Traumatic |

UE, LE |

16 (1/15) |

34 (11) [22–59] |

Distal articular location (wrist, hand, ankle foot) Comorbidities (e.g. alcoholism) Polytrauma |

Return to work |

|

|

De Mos et al., 2009 (12) |

Retrospective |

IASP (4) |

5.8 years (2.1–10.8) |

NR |

NR |

102 (81/21) |

51 [12–86] |

Upper extremity Initiating event other than fracture Cold skin temperature |

Self-reported recovery and work status |

|

|

Table III. Contd. |

||||||||||

|

Author, year |

Study design |

Diagnostic criteria |

Disease durationa |

Initiating event |

Location |

n (f/m) |

Age, yearsa |

Positive prognostic factors |

Negative prognostic factors |

Outcome |

|

Eulry et al., 1990 (13) |

Retrospective |

Doury (23) |

Atraumatic: 5.2 months [0.5–22] Traumatic 3.7 months [0.1–13] |

Traumatic, atraumatic |

LE |

199 (60/139) |

34.2 (17.4) [11–84] |

Psychological background in non-traumatic CRPS |

Improvement or cure |

|

|

Goris et al., 1990 (14) |

Prospective |

NR |

NR |

Traumatic, atraumatic |

UE, LE |

441 (316/125) |

(44) [10–83] |

Cold skin temperature Exercise induced exacerbation of the symptoms |

Duration of disease |

|

|

Laulan et al., 1997 (15) |

Prospective |

Clinical algodystrophy score (15) |

NR |

Wrist fracture |

UE |

102 (68/34) |

54.8 |

Severe initial injury Pain at distal radio-ulnar joint Clinical algodystrophy score > 7 at 6 weeks |

Clinical algodystrophy score (15) |

|

|

Sandroni et al., 2003 (7) |

Retrospective |

IASP |

11.6 months (12.4) |

Traumatic, atraumatic |

UE, LE |

74 (NR) |

46.9 (16) [15–86] |

Fracture as initiating event Absence of sensory symptoms Presence of objective swelling |

Other initiating events (e.g. crush, sprain, contusion) |

Resolution rate |

|

Tan et al., 2009 (16) |

Retrospective |

Veldman |

NR |

Traumatic, atraumatic (onset of CRPS in childhood, age <16 years) |

UE, LE |

42 (37/5) |

25.5 [16–34] |

Disease duration on physical functioning on SF-36 |

Male gender Age at onset <16 years Low score on SF-36 on general health and physical functioning |

SF-36 |

|

van der Laan et al., 1998 (17) |

Retropsective |

Veldman |

NR |

Traumatic, atraumatic |

UE, LE |

1,006 (763/243) |

43.3 |

Age at onset: patients developing complications were younger than patients without complications (median 35 years vs. 44 years)) Female gender Lower extremity Initially cold skin temperature Complications (infection, ulcers, chronic oedema, dystonia, myoclonus) |

Development of complications (infection, ulcers,chronic oedema, dystonia, myoclonus) and development of CRPS in another limb |

|

|

Vaneker et al., 2005 (18) |

Prospective |

Veldman |

> 8 years |

NR |

UE |

47 (33/14) |

58 (15) |

Cold skin temperature Increased pressure hyperalgesia on affected limb with disease progression |

Visual analogue scale Skin temperature at diagnosis (warm, cold) |

|

|

Vaneker et al., 2006 (19) |

Retrospective |

Veldman |

< 12 months |

NR |

UE |

45 (32/13) |

51 (15) |

High pain intensity on visual analogue scale |

Impairment level sum score (6) |

|

|

Zyluk, 1998 (20) |

Retrospective |

NR |

NR |

Traumatic, atraumatic |

UE |

112 (75/37) |

58.2 [23–84] |

Symptoms >12 months, CRPS stage 2 (dystrophic) and stage 3 (atrophic), coexistence of misdiagnosed nerve injuries or nerve compression |

Pain, finger flexion |

|

|

UE: upper extremity, LE: lower extremity, NR: not reported; f: female; m: male; CRPS: complex regional pain syndrome. aValues given as mean (standard deviation) and [ranges]. |

||||||||||

The preferred diagnostic criteria were the Veldman criteria (21) (n = 5 (11, 16–19)) and the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) criteria (4) (n = 2 (7, 12)). In one prospective and two retrospective studies no diagnostic criteria were reported (10, 14, 20).

Prognostic factors

A wide spectrum of outcome parameters were investigated, including self-reported symptoms (7, 16, 18, 20), clinical severity scores (10, 15, 19), development of complications (17), duration of disease (14) and return to work (11, 12). The included studies revealed a total of 28 prognostic factors. Cold skin temperature (n = 5) (10, 12, 14, 17, 18) and the presence of sensory disturbances (n = 3) (15, 18, 19) appear to represent parameters associated with a poor prognosis of CRPS 1. For details see Table IV.

We found no study developing or validating a prognostic instrument to identify patients with poor CRPS 1 prognosis. Moreover, the evidence at hand did not allow a diagnostic algorithm to be developed.

|

Table IV. Prognostic factors grouped within 7 clinical clusters |

||

|

Cluster |

Positive prognostic factors |

Negative prognostic factors |

|

Gender (n = 3) |

Female (17) Male (10, 16) |

|

|

Age (n = 3) |

Age at onset < 40 years (10) Median age at onset 35 years (17) Age at onset < 16 years (16) |

|

|

Diagnosis (n = 1) |

Delayed diagnosis (> 2 months after initiating event) (10) |

|

|

Initiating event (n = 5) |

Fracture (7) Spontaneous onset CRPS (10) |

Polytrauma (11) Initiating event other than fracture (12) Severe initial injury (15) |

|

Localization (n = 4) |

Distal articular location (11, 15) Upper extremity (12) Lower extremity (17) |

|

|

Clinical features (n = 19) |

Absence of sensory changes (7) Swelling (7) Disease duration (16) |

Exercise-induced pain (14) Sensory disturbances (15, 18, 19) Initially cold skin temperature (17) Cold skin temperature (10, 12, 14, 17, 18) Complications (infection, ulcers, chronic oedema, dystonia, myoclonus) (17, 18) Clinical algodystrophy score > 7 (7) Low score on general health in SF-36 (16) Disease duration > 1 year (20) Coexistence of misdiagnosed nerve injury or compression (20) |

|

Contextual factors (n = 2) |

Comorbidities (e.g. alcoholism) (11) Psychological background in non-traumatic CRPS (13) |

|

|

CRPS: complex regional pain syndrome. |

||

DISCUSSION

Main findings

This systematic review revealed a wide scatter of general prognostic factors in CRPS 1 that were sometimes contradictory. Clinical manifestations, such as the presence of cold skin temperature (10, 12, 14, 17, 18) and sensory disturbances (15, 18, 19), seem to represent parameters associated with a poor prognosis in CRPS 1. Only a few studies used reliable and validated measures to assess prognostic factors and co-factors that might influence the course of the condition. Therefore, no assumption can be made regarding the causality of these findings. We failed to quantify and rank order prognostic parameters and we were unable to derive an algorithm allowing clinicians to assess patients’ prognosis at early stages of the disease.

Results based on the included literature

To the best of our knowledge this is the first attempt systematically to identify and consolidate the prognostic factors that influence the course of CRPS 1. Despite broad inclusion criteria, only a small number of studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria. This suggests that prognostic aspects of CRPS 1 have received little attention in high-level methodological research.

Our findings are in line with the results of a recently published Delphi survey (24). In the absence of evidence-based prognostic factors, the authors performed a survey aimed at reaching an expert consensus on poor prognostic factors in CRPS 1. The expert panel agreed on 49 items, which, in their opinion, are associated with poor prognosis in CRPS 1. These factors consisted primarily of clinical manifestations, such as sensory disturbances and cold skin temperature. For many factors, we found only weak (disease duration, comorbidities) or conflicting evidence (localization, initiating event). For example, consensus was reached that onset after a fracture is likely to result in a poor prognosis, whereas Sandroni et al. (7) found a higher resolution rate if CRPS 1 appeared after a fracture than after other triggering events.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is the application of a robust systematic review methodology. A comprehensive review of the literature based on a broad search of all relevant databases and the additional search of bibliographies of included studies, retrieved review articles and current treatment guidelines reduces the risk of selection bias. All relevant reports were searched systematically and without language restriction.

The limitations of our study are two-fold. First, by the restriction of our search to 1990 onward, we potentially missed some important papers. Secondly, overall the quality of the included studies was scarce. The mean number of subjects in the included studies was small and the quality of retrospective and prospective reporting was often limited. Moreover, different diagnostic criteria for CRPS 1 were used and 3 studies did not report any definition of CRPS 1. We found no systematic difference in the patterns of prognostic factors reported and therefore decided to report the results jointly. Thus, variability in study characteristics, diagnostic criteria, outcomes and follow-up periods impeded us from providing a quantitative analysis, resulting in only a systematic description and an inventory of prognostic parameters.

Implications for research

The results of this review suggest the need for large prospective cohort studies aimed at predictors of outcome and effective interventions. CRPS 1 is a syndromal condition and all currently used diagnostic criteria show relatively good negative, but only moderate positive, predictive values (i.e. increased likelihood of false positives) (25). Until diagnostic criteria improve, future research should focus on the identification of relevant prognostic factors that influence the course of disease. A defined prognostic profile may compensate for the current lack of diagnostic precision and will allow clinicians to guide treatment according to risk profile. This will further enhance treatment outcomes in at-risk patients and may prevent the overtreatment of patients with a favourable course of the disease. We are aware of one ongoing study in Switzerland following patients with suspected CRPS 1 of the hand or the foot through their observational study over a period of 1–2 years (26) and we encourage similar research in other countries.

Secondly, whereas these patients may be identified early, there still is a relative lack of evidence about the utility of various modalities with which patients may be treated. We require sufficiently powered intervention studies investigating the efficacy of various treatment options in CRPS 1 management. These studies should focus on classifying subgroups of patients and risk profiles that are associated with an unfavourable or favourable treatment response.

Recently, a multidisciplinary task force from the Netherlands completed a systematic review of the CPRS literature and summarized their findings in evidence-based treatment guidelines (27). The authors concluded that, to date, due to insufficient data, no strong treatment recommendations could be made in treatment guidelines for CRPS. This highlights the need for further and conjoint research in all fields of medicine, to broaden our knowledge about this syndrome.

Implications for practice

To date, practitioners assess the prognosis of patients with CRPS 1 based on individual clinical experience. Our findings indicate that little is known about prognostic relevant factors predictive of an unfavourable course of the disease. Although epidemiological studies suggest that many mild forms of CRPS 1 resolve spontaneously (7), it is clinically important and relevant to recognize prognostic factors associated with unfavourable outcome. Timely identification of negative predictors will most likely lead to early referral for current best practice treatment and therefore better treatment outcome. One promising method could be a severity score (28), which may help guide treatment intensity. However, to date, the impact of such a score on treatment outcome is unknown and requires further investigation.

In addition, as our systematic review highlights, nearly all prognostic factors identified in the Delphi Survey (24) are currently not, or are only weakly, supported by the existing evidence, and therefore further research is needed. Based on our review, patients with clinical features including sensory disturbances and cold CRPS 1 are likely to have an unfavourable course of disease and should be treated aggressively. Physicians treating patients with CRPS 1 are therefore strongly encouraged to include patients in a registry in order to further enhance our knowledge about the disease.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review highlights the need for studies investigating prognostic factors for the course of CRPS 1 that allow clinicians to define a specific risk profile in patients. The current evidence is weak, and consistency was found only for negative predictive features, such as sensory disturbances and cold skin temperature. These findings are in agreement with a consensus on poor prognostic factors reached by an expert panel. However, for many other proposed relevant factors, we were unable to identify evidence to support their influence on the course of the disease. We presume that this finding is due to lack of evidence regarding the aetiological and prognostic understanding of CRPS 1. Further research should therefore aim to investigate the clinical value of factors believed to be of importance both for the development and the course of the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Ltd, York, UK for their support in the literature search.

REFERENCES