OBJECTIVE: Cost-effectiveness of a geriatric rehabilitation programme.

DESIGN: Economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial.

METHODS: A total of 741 subjects with progressively decreasing functional ability and unspecific morbidity were randomly assigned to either an inpatient rehabilitation programme (intervention group) or standard care (control group). The difference between the mean cost per person for 12 months’ care in the rehabilitation and control groups (incremental cost) and the ratio between incremental cost and effectiveness were calculated. Clinical outcomes were functional ability (Functional Independence Measure (FIMTM)) and health-related quality of life (15D score).

RESULTS: The FIMTM score decreased by 3.41 (standard deviation 6.7) points in intervention group and 4.35 (standard deviation 8.0) in control group (p = 0.0987). The decrease in the 15D was equal in both groups. The mean incremental cost of adding rehabilitation to standard care was 3111 euros per person. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for FIMTM did not show any clinically significant change, and the rehabilitation was more costly than standard care. A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve suggests that if decision-makers were willing to pay 4000 euros for a 1-point improvement in FIMTM, the rehabilitation would be cost-effective with 70% certainty.

CONCLUSION: The rehabilitation programme was not cost-effective compared with standard care, and further development of outpatient protocols may be advisable.

Key words: randomized controlled trial; cost-effectiveness; rehabilitation; aged; health/social services for the aged; frail elderly.

J Rehabil Med 2010; 42: 949–955

Correspondence address: Sari Kehusmaa, Social Insurance Institution, Research Department, Peltolantie 3, FI-20720 Turku, Finland. E-mail: sari.kehusmaa@kela.fi

Submitted November 26, 2009; accepted August 30, 2010

INTRODUCTION

Populations are ageing progressively worldwide. The proportion of over 65-year-olds is expected to increase to 10% by 2025, amounting to 800 million people globally (1). It is assumed that this will lead to an increase in demand for long-term care (2–4). In the USA alone, the number of nursing home residents is expected to reach 3 million by 2030 (5). Geriatric rehabilitation is assumed to prevent deterioration in health and increase independence in activities of daily living, thereby delaying elderly persons’ need for institutional care. However, the benefits of inpatient geriatric rehabilitation and its cost-effectiveness among frail elderly people are somewhat unclear. According to recommendations, geriatric rehabilitation should focus on high-risk groups, use an interdisciplinary team approach, and assess the outcomes with standardized measures (6–8).

The Social Insurance Institution of Finland (SII) has designed a rehabilitation programme specifically for frail older persons with progressive functional disability. In this study, the target group consisted of frail home-dwelling older persons with unspecific morbidity and progressive disability development, and we aimed at avoiding restrictive inclusion criteria (8, 9). As an indication of frailty, subjects eligible to the study had to meet the criteria for entitlement to the SII Pensioners’ Care Allowance, a benefit that is granted to a person with a medical disability and who is verified by a physician to be in need of assistance. This empirical and multidimensional definition of frailty covers biological, physiological, social and environmental changes. We did not use any specific disease or co-morbidity as a measure of frailty.

The aim of the SII rehabilitation programme is to support older persons so as to enable them to live independently at home for as long as possible. A randomized controlled trial was set up to evaluate the effectiveness of the rehabilitation (10). Additionally, clinical outcomes were assessed using functional ability (11) and health-related quality of life (12) measures. This paper reports on the cost-effectiveness of this rehabilitation programme. For the economic evaluation, data were collected on the rehabilitation costs, healthcare costs, costs of services for old people, and costs of institutional care.

METHODS

Participants and randomization

The design and content of the study have been described in detail previously (10, 13–15).

The inclusion criteria for participants were: age 65+ years, progressively decreasing functional ability, and risk of institutionalization within 2 years. For subjects to qualify for the study, their functional status must have been weakened and they must have been in need of regular formal home help or home nursing or similar informal assistance. Representatives of the local social and health services were instructed to identify and recruit for the study persons whose coping at home was threatened. The exclusion criteria were acute or aggressively progressing diseases that would prevent participation in rehabilitation, severe cognitive impairment (fewer than 18 points in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (16)), or participation in an inpatient rehabilitation during the preceding 5 years.

Subjects were enrolled during the year 2002 through a two-phase selection process. Initially, potential participants were recruited by the local social care and healthcare officials in 41 municipalities. In the second phase, the representatives of the relevant municipality, rehabilitation centre and local SII office jointly assessed the selected candidates’ eligibility and suitability for rehabilitation. The intention was to find 18 persons from each municipality to be randomized into intervention subjects (n = 8), controls (n = 8) and substitutes (n = 2). Altogether, 741 persons (mean age 78 years, range 65–96 years) were approved for the study, and prior to randomization, they underwent baseline assessments performed by 3 physiotherapists.

After the baseline assessments, subjects were randomly allocated to intervention (n = 332), control (n = 317) and substitute (n = 92) groups by using numbered and sealed envelopes stratified by gender. The substitute subjects were to replace possible drop-outs before the intervention (n = 33) and to complement the groups in rehabilitation centres to make them comparable in size (n = 11), and finally, the remaining subjects were integrated in the control group (n = 48). The final study population in the intention-to-treat analysis consisted of 376 persons in the intervention group (IG) and 365 persons in the control group (CG) (Fig. 1). To avoid any regional differences in “standard care protocol” or supply of services, randomization was done by districts.

This study was approved by the ethics committees of the SII and Turku University Hospital. All of the study participants gave their written consent to the study.

Intervention

The study was implemented in 41 municipalities and 7 independent rehabilitation centres. Subjects in the intervention group participated in 3 separate inpatient periods at the rehabilitation centre during the course of 8 months (the preliminary evaluation period lasted 5 days, intensive rehabilitation 11 days and follow-up 5 days).

Although the SII prepared written standards concerning the contents and goals of the geriatric rehabilitation programme, it was necessary to take into account possible differences in the practices between the various rehabilitation centres, and hence, a multicentre trial design was used. Subjects in the control group received standard healthcare and social services, and they did not have access to inpatient rehabilitation during the 12-month intervention period.

The initial evaluation period at the rehabilitation centre included a comprehensive geriatric assessment. The participants were examined by a multidisciplinary team, led by a physician, and they received an individualized plan for future rehabilitation activities in order to support their capacity for independent living. The key members of the rehabilitation team (including physician, physiotherapist, social worker, occupational therapist) met personally with each participant. In addition, they took part in group activities, which in most cases involved physical activity.

In contrast to the individually focused evaluation period, the second period was based primarily on group activities. Adaptation coaching was used to motivate the participants to adopt an active lifestyle and coping strategies for independent living. The participants attended classes given by the members of the rehabilitation team. Topics covered, for example, promotion of self-care, nutritional advice, discussions about mood, medical aspects, advice on social services and recreational activities. The majority of group activities focused on physical activation. According to their individual needs, the participants received psychological or other counselling. With the social worker, they talked about issues related to their life situation (e.g. living arrangements, need for assistance and social network).

Prior to the second period, an occupational or physical therapist made a visit to every subject’s home, together, when possible, with a representative of the local social service team. They evaluated the subject’s needs for home support and services.

The third rehabilitation period took place 6 months after the first period. The aim of this period was to refresh the instructions given during the intensive rehabilitation period and to readjust the home-training regimen, if necessary.

Outcome measures

Health-related quality of life (HRQol) and functional ability were used as outcome variables. HRQol was assessed using the 15D score (3, 12) and functional ability by means of the Functional Independence Measure (FIMTM). The 15D questionnaire is a generic HRQoL instrument that consists of 15 dimensions: mobility, vision, hearing, breathing, sleeping, eating, speech, elimination, usual activities, mental function, discomfort and symptoms, depression, distress, vitality and sexual activity. Each dimension is divided into 5 ordinal levels. The respondent chooses always from each dimension the level, which best describes her/his present health status. A set of utility or preference weights is used to generate the 15D score (single index number) on a 0–1 scale. If the subject dies during follow-up the 15D score is set to be 0.

The FIMTM measures independent performance in self-care, sphincter control, transfers, locomotion, communication, and social cognition. The FIMTM instrument consists of 18 items and each item score ranges from 1 to 7: an item score of 7 is categorized as “complete independence”, while a score of 1 stands for “total assistance” (the subject performs less than 25% of a task). Scores below 6 require another person for supervision or assistance. The total score ranges from 18 (the lowest) to 126 (the highest level of independence) (11). It has been shown that the total FIMTM scores can be treated as interval values (17). A clinically significant improvement in FIM equals 22 points (18–21).

For this study, the FIMTM assessments were carried out at the local health centres in each subject’s home municipalities by 3 independent and accredited examiners, who were qualified physiotherapists, extensively trained for these assessments, and without any role in the intervention. The 15D questionnaire had been sent in advance to each subject who were asked to complete and bring it along to the health centre. The questionnaire was checked by the examiner on arrival at the health centre and any incomplete sections were completed by interviewing the participants. The procedure was repeated at the 12-month follow-up, and the differences between the baseline and 12-month follow-up assessments were used as outcome measures.

Utilization of services

In order to estimate the total costs of care for the participants, data were collected on the utilization of a wide range of services. Various national registers were used as sources of information, whenever possible. Use of health services covered all hospital admissions, as well as inpatient care in general hospitals, private hospitals and health centres. Data on inpatient care and day case surgery were drawn from the National Hospital Discharge Registry (HILMO) (22). Use of outpatient care in the private sector and use of prescription medicines in outpatient care were obtained from the SII databases (23). A questionnaire completed by the subjects was used to collect data on outpatient care in the public sector, including visits to general practitioner and to outpatient clinics.

Data on institutional care and sheltered housing as well as on the use of professional home care and home help services were derived from questionnaires. Service use questionnaires are commonly used as a method to measure service components in clinical trials if register data are not available. The main disadvantage of this method is that it relies on the memory of interviewees. This constitutes a problem in elderly populations. Instead of using a self-report questionnaire, we asked the municipal social care and healthcare officials to collect service use data from individual care and service plans. In Finland, municipalities are the main provider of services to elderly people, and municipal records about service use are very reliable. The data derived from questionnaires were cross-sectional at baseline and 12-month follow-up. In cases where changes occurred in the service use during the follow-up, the data compiled for one year consist half of the services used at the baseline and half of the services used at the follow-up.

Costs

A societal perspective was applied in the costs assessment. The unit costs of the rehabilitation were obtained from the SII registers. For the monetary valuation of the health and social care services, we used national standard costs information and prices from the year 2001. Standard costs represented the average costs defined on the basis of a national standard cost study (24). Because the follow-up time was one year, we did not discount the costs or health benefits.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out by using the intention-to-treat approach. A total of 645 subjects (87%) completed the follow-up assessment at one year (Fig. 1). Descriptive statistics are reported for the variables of interest. Differences in median costs between the groups were tested with the Kruskal-Wallis test. To assess differences between groups, p-values for the outcome variables were tested with mixed model analyses (SAS Proc Mixed version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Missing values arose from several sources: withdrawal from the study, failure to fully complete questionnaires, or failure to complete particular items within a questionnaire. The incomplete data concerned especially the 15D questionnaire dimension 15, dealing with the influence of health status on sexual well-being. An imputation model was constructed to impute values for the unobserved dimensions in the 15D questionnaire (25). A model was fitted for each dimension of 15D with missing values. After multiple imputations, 20 plausible versions of the complete data existed and each of them were analysed by using the standard complete data method. The results of the 20 analyses were then combined to produce a single result (26, 27).

Cost-effectiveness was assessed for the outcomes in FIMTM and the 15D score. Cost-effectiveness of rehabilitation was compared with standard care using the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). Bootstrapping technique was used to quantify uncertainty in cost-effectiveness point estimates. This method re-samples the original data in order to build an empirical estimate of the sampling distribution of the ICER (we used 10,000 replications). Confidence intervals were calculated from this simulated empirical data (28).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the subjects

At baseline, the mean age of the subjects was 78.4 years (age range 65–96 years). A majority of them were female (86%) and widowed (62%), lived alone (72%) in an urban area (70%), and had perceived deterioration in their health during the preceding year (66%). Detailed baseline characteristics of the study groups are shown in Table I. Differences between IG and CG were insignificant at the baseline.

| Table I. Baseline characteristics |

| Characteristic | Total sample n = 741 | Intervention group (IG) n = 376 | Control group (CG) n = 365 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 78.4 (6.6) | 78.2 (6.6) | 78.6 (6.6) |

| Male, n (%) | 102 (14) | 55 (15) | 47 (13) |

| GDS, mean (SD)* | 4.17 (2.5) | 4.14 (2.5) | 4.2 (2.5) |

| Depressive mood | | | |

| GDS 7–13, n (%) | 132 (18) | 70 (18) | 62 (17) |

| MMSE, mean (SD)† | 25.2 (3.0) | 25.3 (2.9) | 25.1 (3.0) |

| Declined cognitive capacity | | | |

| MMSE < 24, n (%) | 210 (28) | 103 (27) | 107 (29) |

| HRQoL 15D, mean (SD)‡ | 0.73 (0.1) | 0.73 (0.1) | 0.74 (0.1) |

| FIM, mean (SD)§ | 115.6 (7.9) | 115.9 (7.2) | 115.4 (8.6) |

| Self-rated health, n (%) | | | |

| Very good | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| Quite good | 28 (3.7) | 12 (3.2) | 16 (4.4) |

| Neither good nor poor | 484 (65.3) | 250 (66.5) | 234 (64.1) |

| Rather poor | 210 (28.4) | 103 (27.4) | 107 (29.3) |

| Very poor | 17 (2.3) | 9 (2.4) | 8 (2.2) |

| Widowed, n (%) | 462 (62) | 242 (64) | 220 (60) |

| Living alone, n (%) | 535 (72) | 279 (74) | 256 (70) |

| Living in an urban area, n (%) | 516 (70) | 256 (68) | 260 (71) |

| Perceiving health deterioration during preceding year, n (%) | 488 (66) | 254 (68) | 234 (64) |

| Informal care, n (%) | | | |

| Yes | 558 (75) | 288 (77) | 270 (74) |

| No | 169 (23) | 77 (20) | 92 (25) |

| Missing information | 14 (2) | 11 (3) | 3 (1) |

| Formal home help visits/week, mean (SD) | 2 (5.0) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (5.5) |

| * GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale, maximum 15, values 0–6 indicate non-depression. † MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination, maximum 30, values under 24 indicate existence of dementia. ‡ 15D: Health-related Quality of Life score, range 0–1, 1 indicates the best imaginable health. § FIM: Functional Independence Measure, max 126, 3 subscales (Self Care 8 items, Mobility 5 items, Cognition 5 items) were formed from 18 items (range: 1 = total assistance – 7 = complete independence). |

The 3 most typical diagnoses for the participants to be entitled to receive SII Pensioners’ Care Allowance were arthrosis (14%), ischaemic heart disease (11%) and cerebrovascular disorders (9%). No differences were found in these percentages between the groups. Depressive mood (Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) = 7–13 points) was found in 17% and declined cognitive capacity (MMSE < 24 points) in 28% of the subjects.

Effects of interventions

During the 12-month follow-up, there was no statistically significant change in the FIM™ score between IG and CG (p = 0.0987) (Table I). The 15D score decreased to an equal extent in each group. Due to many missing values in one dimension of the 15D, the analysis was conducted also for 14D without this particular dimension. In addition, the single imputation (decline in IG 0.016 and CG 0.015) and multiple imputations (decline in IG 0.016 and CG 0.016) techniques were used to impute the missing values. The differences between groups in the 15D scores remained non-significant despite these modifications.

Utilization of services and costs

During the 12-month follow-up, a total of 377 (51%) of participants (184 in IG, 193 in CG) received public-sector inpatient healthcare. Mean costs per person were 5509 Euros (6119 euros in IG, 4927 euros in CG). The majority of the participants (561, (76%)) visited a health centre or hospital outpatient department for outpatient care (270 in IG, 291 in CG). Mean costs per person were 197 euros (201 euros in IG, 192 euros in CG). IG resorted more frequently to examinations and treatments in the private sector than the CG did (300 vs 269), but the difference in costs of private sector health care did not differ between the groups (p = 0.59). Mean healthcare costs were similar in both groups (Table II).

| Table II. Outcomes and incremental cost-effectiveness in functional independence and health-related quality of life |

| Outcome measure | Time-point | Intervention group | Control group | p-value for Group effect | p-value for Time effect | p-value for Time* Group effect | Incremental effectiveness | Incremental costs (euros) | ICER | ICER CI Empirical

estimate for CI based on bootstrapped data |

| FIM™ | | | | | | | 0.9 | 3,111 | 3,457 | 650–12,340 |

| | Baseline | 115.85 | 115.38 | | | | | | | |

| | 12 months | 112.44 | 111.03 | 0.1296 | < 0.0001 | 0.0987 | | | | |

| HRQoL 15D | | | | | | | –0.001 | 3,111 | –3,111,000 | 3,269,000–3,576,000 |

| | Single imputation | | | | | | | | | |

| | Baseline | 0.735 | 0.735 | | | | | | | |

| | 12 months | 0.719 | 0.72 | 0.9463 | < 0.0001 | 0.9463 | | | | |

| HRQoL (14D) | | | | | | | | | |

| | Baseline | 0.695 | 0.695 | | | | | | | |

| | 12 months | 0.679 | 0.679 | 0.9443 | < 0.0001 | 0.9883 | | | | |

| All values are means. For FIM™ and 15D, the scores decreasing during the 12-month follow-up indicate a decline in functional independence and health-related quality of life. p-values were tested with a mixed procedure. Means of the incremental effectiveness were analysed for health-related quality of life and functional independence (intervention group-control group). Less decrease in FIM™ in intervention group was signed positive. More decrease in health-related quality of life (15D) in intervention group was signed negative. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) = ∆Costs/∆Effects. Empirical estimate for ICER CI was calculated from bootstrapped data (10,000 replications) as 5 and 95 centiles of sampling distribution. ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; CI: confidence interval; FIM™: Functional Independence Measure; HRQoL: Health-related Quality of Life. |

The aim of the intervention was to support and promote independent living at home. Table III shows the utilization of institutional care and sheltered housing. A total of 41 (11%) persons in IG and 35 (10%) in CG received institutional care. The costs of institutional care tended to be higher in CG because they were more often in need of 24-h assistance (p = 0.062). Home help visits caused the majority of costs for social services. Altogether 324 (44%) participants were home help clients (163 in IG, 161 in CG).

| Table III. The use of health and social care services and the related costs |

| Cost | Intervention group | Control group |

| Users n | Mean

number of

visits/person | Cost/person | CI for the

costs Euro | Users n | Mean

number of

visits/person | Cost/person Euro | CI for the costs | Kruskal-Wallis Test Pr > χ2 |

| Healthcare in public sector: | | | | | | | | | |

| Outpatient care | 270 | 2.7 | 202 | 188–215 | 291 | 2.5 | 192 | 179–205 | 0.37 |

| Day case surgery | 39 | 3.7 | 751 | 699–804 | 24 | 3 | 797 | 690–904 | 0.63 |

| Inpatient care (inc. medicines) | 184 | 4 | 6119 | 5040–7199 | 193 | 2.8 | 4927 | 4028–5826 | 0.16 |

| Healthcare in private sector: | | | | | | | | | |

| Examinations and treatments | 300 | | 490 | 415–565 | 269 | | 430 | 372–488 | 0.59 |

| Prescribed medicines: | | | | | | | | | |

| Outpatient care | 373 | | 1206 | 1103–1310 | 362 | | 1133 | 1042–1224 | 0.34 |

| Services for older people: | | | | | | | | | |

| Home help | 163 | | 8333 | 6774–9892 | 161 | | 9014 | 7040–10,987 | 0.79 |

| Meals-on-wheels | 76 | 253.5 | 1876 | 1702–2049 | 80 | 264.6 | 1958 | 1801–2114 | 0.69 |

| Cleaning service | 96 | 22.8 | 507 | 435–580 | 103 | 21.3 | 476 | 384–567 | 0.08 |

| Home nursing | 135 | 34 | 1370 | 1065–1674 | 156 | 40.3 | 1625 | 1146–2104 | 0.91 |

| Institutional care and sheltered housing | 41 | | 7930 | 5047–10813 | 35 | | 9278 | 6256–12,301 | 0.06 |

| Total costs without rehabilitation: | 376 | | 10283 | 9065–11500 | 365 | | 10375 | 8917–11834 | 0.41 |

| Costs of the rehabilitation | 376 | | 3522 | 3440–3602 | | | | | |

| Total costs | 376 | | 13486 | 12281–14691 | 365 | | 10375 | 8917–11834 | < 0.0001 |

| CI: Confidence interval. |

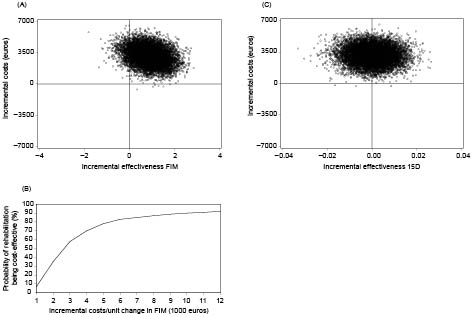

Without the costs of rehabilitation, the costs per person of all health and social care services were similar in both groups, but with the rehabilitation costs included, the total costs were higher in IG than in CG (13,486 vs 10,375 euros per person). The costs-effectiveness planes for the FIMTM and the 15D score are shown in Fig. 2. In terms of the FIMTM, the difference between groups was only one point in favour of the rehabilitation protocol, which cannot be regarded as a significant difference. The rehabilitation was also more costly than the standard care protocol. The 15D score showed no difference between the groups in health-related quality of life.

Fig. 2. (A) Cost-effectiveness plane for functional independent measure (FIMTM) (incremental costs (euro)/incremental effectiveness of FIMTM). (B) Acceptability curve for FIMTM (proportion cost-effective (%)/willingness to pay (euro) per FIM™ point). (C) Cost-effectiveness plane for 15D (incremental costs (euro)/incremental effectiveness 15D).

The costs-effectiveness acceptability curve (Fig. 2) shows that if decision makers were willing to pay 4000 euros for an improvement of one point in FIMTM, the rehabilitation would be cost-effective with 70% certainty. Certainty increases to 83%, if the threshold value of willingness to pay is raised to 6000 euros. The costs-effectiveness plane for the 15D score shows that rehabilitation did not achieve a clinically significant effectiveness (a minimum of 0.02 unit change in the 15D score) (Fig. 2). We have included a wide spectrum of frail elderly to participate in our study. No sensitivity analysis was undertaken, as most of the variations in costs or outcomes were included in the bootstrap estimates of variation in the ICER.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the rehabilitation programme was to maintain functional independence of frail older people with a progressively decreasing functional ability and high projected risk for institutionalization. During the follow-up period, functional independence, measured by the FIMTM score, did not show any clinically relevant decline. The 15D scores impaired to an equal extent in both groups. For frail older persons, a 0.02 unit change in 15D represents a normal decline in health-related quality of life during one year (12). Our study is the case of weak dominance: the difference in effects is not statistically significant, while the difference in costs is significant (29). In other words, the rehabilitation programme designed for frail elderly was not more cost-effective than standard care.

It is possible that the 12-month follow-up was too short a period to accomplish such costs savings in service use that would cover the costs of rehabilitation. In this programme the rehabilitation costs were, on average, 3522 euros per person. Even though a larger number of subjects in IG were institutionalized at 12 months, the costs of institutional care were higher for the CG subjects because they were more often in need of 24-hour assistance. IG subjects were more frequently examined and treated in the private sector. This may be due to the simple fact that certain previously unidentified and untreated disorders were discovered during the multidisciplinary rehabilitation. As the waiting lists in the public sector are often long, the elderly persons may have preferred the private sector for more expedient treatment.

In this study, clinically relevant outcome instruments with proven reliability, validity and sensitivity were used to assess the effectiveness of rehabilitation. However, it is possible that the 15D and the FIMTM measures were not capable of showing all of the positive effects of rehabilitation, such as potential improvements in mood or ability to cope with present health status. Although the FIMTM is a practical tool and widely used as a rehabilitation outcome instrument (30), limitations in its applicability in other than acute care settings are reported (31). Also, the respondents completed some dimensions of 15D rather poorly, especially the dimension concerning the effects of health status on sexual well-being. However, when this dimension was removed from the analysis, the developments in HRQoL remained similar in both groups.

There are several strengths of our study. The sample size was adequate and randomization was carried out rigorously and, consequently, there were no baseline differences between the groups. In both intervention arms, similar and rather high follow-up rates were achieved. The costs were collected for a wide variety of healthcare and social services from a societal point of view. The recall bias was controlled by using national registry data on the use of services, whenever possible.

For this study, we preferred to apply an operational and empirical definition of frailty, which is based on the Pensioners’ Care Allowance benefit granted by the SII. This definition embodies a multidimensional approach and covers biological, physiological, social and environmental changes. We did not use disease or co-morbidity as a measure of frailty. In our study, the exclusion criteria are meant solely for the purpose of identifying those who would not be capable of participating in the full trial. The objective was to facilitate the participation by a broad spectrum of frail elderly people. The generalizability of the results was our concern, and that is why we adopted the more general approach.

Nevertheless, our study also has limitations. The heterogeneity of frail elderly persons in the groups under comparison may affect our results. The gains and losses associated with rehabilitation as observed in our analysis should be considered as averaged over a frail population. Inevitably there are individuals who benefit from rehabilitation. Possibly, if we had applied a more individual approach in the rehabilitation activities, the heterogeneous target group might have gained more from it. However, as this was an randomised control trial study, the intervention had to be standardized in terms of structure and main contents. Previous studies provide evidence that physical interventions are most successful in improving the physical and mental health of elderly people when the participants are divided in groups based on their varying functional abilities (32, 33).

Because of lack of national registries, data on municipal primary health and social care services were collected from the questionnaires completed by the subjects and from the local social and healthcare units. It was, however, not possible to collect data on service use on a more rigorous basis from all of the 41 communities. Therefore, questionnaire data were cross-sectional at baseline and at 12-month follow-up, which may cause some concern of the reliability of cost data. However, even if there is any bias, it has no significant effect on the result in a randomized controlled trial setting. Furthermore, a vast majority of costs were calculated from registry data, which in Finland are regarded as very reliable (34).

To our knowledge, this is the first cost-effectiveness analysis based on a randomized trial of non-disease-specific inpatient rehabilitation for elderly persons. Our results showed that, compared with the standard care protocol, inpatient rehabilitation did not significantly better maintain functional independence in frail older home-dwelling persons. No effects of rehabilitation were detected in terms of health-related quality of life. At the 12-month follow-up, the mean costs of institutional care were lower in IG than in CGs, but the total costs were higher in IG. Future studies are needed in order to explore whether more targeted outpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for particular patient groups is more cost-effective.

REFERENCES