Anette Erikson, PhD, Melissa Park, PhD and Kerstin Tham, PhD

From the NVS Department, Division of Occupational Therapy, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, Sweden

Anette Erikson, PhD, Melissa Park, PhD and Kerstin Tham, PhD

From the NVS Department, Division of Occupational Therapy, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, Sweden

OBJECTIVE: To investigate the meaning of acting with others, in different places over the course of 1 year post-stroke.

METHODS: Qualitative interviews with 9 persons, age range 42–61 years (7 persons with cerebrovascular accident and 2 with subarachnoidal haemorrhage) over the course of a year (i.e. 3, 6, 9 and 12 months) were analysed using a grounded theory approach.

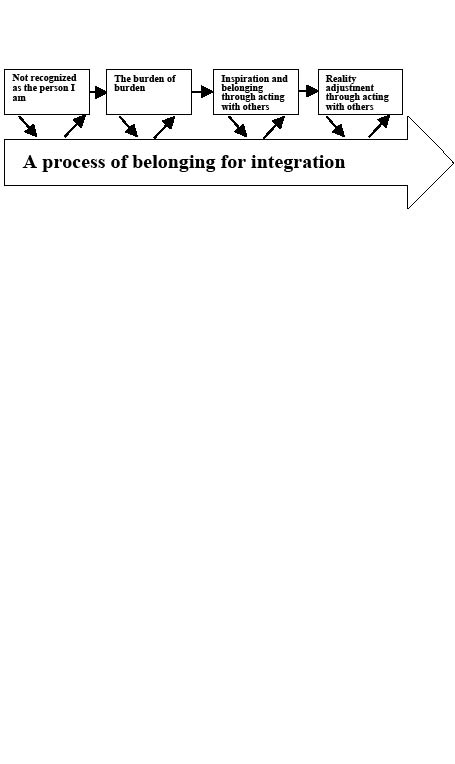

RESULTS: Four categories were identified from the analysis of the participants’ experiences during the year of rehabilitation: (i) not recognized as the person I am; (ii) the burden of burden; (iii) inspiration and belonging through acting with others; (iv) reality adjustment through acting with others. From these categories a core category emerged: a process of belonging for integration.

CONCLUSION: The 4 categories identified suggest that belonging is integral to participation, which is viewed as the goal of rehabilitation.

Key words: occupational therapy; participation; qualitative research.

J Rehabil Med 2010; 42: 831–838

Correspondence address: Anette Erikson, Department of Occupational Therapy, NVS, Karolinska Institutet, Fack 23200, SE-141 23 Huddinge, Sweden. E-mail: anette.erikson@ki.se

Submitted July 13, 2009; accepted July 8, 2010

Introduction

The return to daily life after stroke is a complex process, and it is common that persons with stroke and their significant others (family members, friends or colleagues) experience restrictions in social participation (1, 2). Long-term social and emotional consequences have been shown to be the largest domain of problems in daily life for the person with stroke (3) and challenges in connectedness with, and withdrawal from, others often persist after discharge home from hospital (1, 4). There are also consequences in daily life for other persons in the social network of the person with stroke, such as feelings of uncertainty (5), perceived burden of care (6) and emotional stress, which have been shown to result in negative long-term consequences for partners (2).

Recent studies emphasize the importance of involving both the person with stroke and their significant others in the process of rehabilitation. Today, rehabilitation after stroke focuses primarily on the person with stroke and often takes place in familiar surroundings, such as the home and workplace, which is recommended in the national guidelines for stroke care in Sweden (7). Research has shown that the home environment offers new opportunities for involving significant others in rehabilitation (8).

There are a limited number of studies of how persons with stroke and their significant others experience their interactions in daily activities in the home and how social interaction changes over time. One study identified how patterns in daily activities changed for both spouses in a couple and identified the importance of viewing the couple as a social unit in the process of rehabilitation (9). Some studies have shown the social importance (for persons of working age) of connecting with their workplaces early in the rehabilitation process after stroke (10, 11). There is also some evidence of a positive outcome when families are involved in the rehabilitation (12, 13). However, further research is needed to better understand how social aspects in different settings can be used to support social interaction in real-life situations (14).

The theoretical framework of this study comprises two conceptual tools; humans as socially occupied beings (15, 16) and place-integration (17, 18), which may be useful when focusing on the processes of reintegrating into social worlds through activity after stroke. In line with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)’s interdisciplinary intent (19), the concept of humans as socially-occupied beings is drawn from cultural psychology, anthropology and occupational science, shifting the focus from individualized activity towards the participatory perspective of “doing something with someone that matters” (15, p. 432). This perspective underlines the interrelatedness of persons with others (Carrithers 1992, in 15, p. 426). “Doing-with” integrates the human connectedness that is experienced when engaging in activities and the necessity to create a sense of place or meaning through dynamic transactions with an environment (20, 21). By investigating the experiences of acting together with others during rehabilitation across time, we can better understand the meaning of social interactions in rehabilitation. This knowledge can serve as a basis for the development of rehabilitation interventions emphasizing the interactions between the person with stroke and significant others. The aim of this study was to investigate the meaning of acting with others in different places during the first year of rehabilitation after stroke.

Methods

Charmaz’ (22) interpretation of grounded theory“ (23, p. 9)…as a set of principles and practices, not as prescriptions or packages [to] emphasize flexible guidelines, not methodological rules, recipes, and requirements” was used in this study to conceptualize the meaning of acting with others during a year-long rehabilitation process. The intention in this study was not, as is usually the case in grounded theory, to construct a theory. Rather it was to generate an “abstract theoretical understanding” (22, p. 4) that is represented as the core category in this study.

Participants

A total of 9 participants were chosen for this study. All had acquired stroke, were of working age and were recruited from a rehabilitation department. The initial 7 individuals were drawn from a database of transcribed qualitative interviews conducted with 16 participants at the rehabilitation department. The criteria for participation were: first stroke less than one month ago, working age, limitations in the performance of daily activities, memory or ability to recall daily experiences, and ability to understand and respond to interview questions. The initial 7 participants were chosen because they represented a heterogeneous sample in terms of gender, type of cognitive impairments (i.e. impaired memory, visuospatial, perception, attention and body-image) and diverse experiences, in order to provide rich data on the relationships between aspects of acting with others and engagement in occupations in different places over the year. Further, two additional 2 participants were chosen using theoretical sampling (22, 23) during the analysis in order to elaborate on and refine emerging categories until saturation was achieved. The characteristics of the final 9 participants are summarized in Table I. All participants received written and verbal information about the study and gave their verbal and written informed consent to participate. The study was approved by a ethics committee.

| Table I. Participants’ characteristics | |||||||

| Participant | Sex | Age (years) | Diagnosis | Living conditions | Housing | Education | FIM (motor/ cognitive) |

| 1 | M | 61 | LCVA | Single 2 children | House | Upper secondary school vocational education/training | 89/28 |

| 2 | F | 51 | LCVA | Single, boyfriend 2 children | Flat | Upper secondary school vocational education/training | 90/5 |

| 3 | M | 48 | SAH | Married 2 children | Flat | Upper secondary school, university | 69/5 |

| 4 | F | 55 | LCVA | Single, boyfriend 1 child | Flat | Upper secondary school, university | 89/35 |

| 5 | M | 42 | RCVA | Married 3 children | Flat | Primary and secondary school, vocational education/training | 67/14 |

| 6 | F | 54 | SAH | Single 2 children | House | Upper secondary school, university | – |

| 7 | M | 57 | RCVA | Single, girlfriend 2 children | House | Upper secondary school, university | 90/27 |

| 8 | M | 48 | RCVA | Married 2 children | House | Upper secondary school | 65/23 |

| 9 | M | 45 | RCVA | Married 4 children | House | Upper secondary school, university | 56/22 |

| M: male; F: female; LCVA: left cerebrovascular accident; RCVA: right cerebrovascular accident; SAH: subarachnoidal haemorrhage; FIM: Functional Independence Measure (motor maximum score 91, minimum score 13; cognitive maximum score 35, minimum score 5). | |||||||

Data collection

The longitudinal interview data were collected at months 1, 3, 6 and 12 post-stroke in locations convenient to the participants. At 1 month post-stroke the participants were inpatients at a rehabilitation clinic, which included individualized daily (i.e. occupational therapy and physiotherapy) and intermittent sessions (i.e. social work, psychology and/or speech and language therapy). Weekends were spent in their homes. At 3 months and during the rest of the year, the participants were outpatients at the rehabilitation department. Most of the participants had been in contact with or had visited their work settings by the third month and were receiving rehabilitation there by the end of the year.

The interviews were conducted by two occupational therapists (first and last author) with clinical and research experience in the field of stroke rehabilitation. Following the principles of theoretical sampling and constant comparison (22, 23), the interview guide was developed to follow up on answers to previous interviews. Thus, the participants’ narratives of their experiences during the year of data collection led to new questions relevant for theoretical sampling, while the emerging categories were incorporated into and shaped the interview guide for each subsequent interview. There were two general areas of questioning: (i) experiences performing daily activities relative to those experiences prior to acquiring a stroke, and (ii) experiences of daily life with stroke (e.g. emergent difficulties with activities, others involved, etc.). All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Data analysis began after all the interviews had been completed. It consisted of identifying and systematically comparing similarities and differences in the data at each level of analysis using initial, focused and axial coding (23). The cyclical process in grounded theory of collecting and coding data that usually begins after the first interview was not applied in this study. Instead, initial line-by-line coding began of the interviews across the year of rehabilitation with respect to 7 participants drawn from a large database (28 interviews, approximately 840 pages). This initial coding led to theoretical sampling of 2 further participants (8 interviews, approximately 230 pages) until saturation emerged in the data. This also provided more detailed descriptions of the experiences of performing activities and acting with others in different contexts (the rehabilitation setting, home and work) during the year of rehabilitation. Questions raised during this stage of analysis in the study concerned the changes in the rehabilitation process during the year; for example, what it meant for the participants to perform activities with others (rehabilitation staff, family, friends and colleagues) in different places during the year. The most significant and frequent codes found during the initial coding were then used during focused coding to synthesize and explain the data. Comparing data clarified and further sharpened the definitions of the categories. For example, the category “inspiration and belonging through acting with others” emerged from the initial codes for how participants experienced performing activities with others as both energizing and inspiring. By closely examining these descriptions of doing with others, focused coding also began to distinguish contrasting experiences. For example, participants also felt that the new situation created burdens for others, leading to a new category of “burden of burden”. Finally, in the last stage of analysis, axial coding refined the dimensions of categories by relating them to subcategories. For example, the category “Inspiration and belonging through acting with others” was related to 3 subcategories of “the mattering of acting together with others”, “easing into belonging” and “workplace for social acting and support”.

When the data no longer sparked new theoretical insights nor revealed new properties of the core categories, no further analysis of data was required. The interrelationships between categories emerging from the data during this initial, focused and axial coding formed the core category: A process of belonging for integration (e.g. see Fig. 1) During the entire process, analysis and refinement of categories was ongoing between the first and the third author. To enhance credibility the second author peer examined the last step of the analysis until agreement was reached. These findings were also discussed with an experienced research group as a form of informal triangulation.

Fig. 1. The 1-year long rehabilitation process showing a process of belonging for integration.

Results

Four categories emerged from the analysis: (i) not recognized as the person I am; (ii) the burden of burden; (iii) inspiration and belonging through acting with others; and (iv) reality adjustment through acting with others. From these categories a core category emerged: A process of belonging for integration. Within each of the 4 categories there was a temporal process of 1–12 months. Thus, the temporality is neither linear nor rigid across all participants, but captures a general image of the process of belonging for integration.

Not recognized as the person I am

In the process of belonging for integration and particularly in the initial phase of rehabilitation, the participants described their new situation after stroke as not being recognized. The discrepancy between past and present life was best described by one of the participants as no longer being recognized as the person he had been: “It is obvious, like before you were somebody. I mean both in private and professionally. Then suddenly you are like nothing, just a person in your bed.”

Initially at the hospital he needed someone to speak on his behalf to give him the security he needed: “My wife was with me then, which was really good for me. She could inform me about what was happening and such, stuff, [like] things [that] the personnel wanted to do.... It felt like you needed a healthy person with you when you were ill who could speak for you” (1 month).

Another participant described how he could no longer decide for himself, and was therefore dependent on others understanding and taking “the right” decisions for him: “I decided everything by myself and now others will decide for me, because I haven’t so much brain. I’m not able to think so much” (1 month). Another participant was able to act by herself, and was therefore considered competent by the staff when she was doing activities even though her own experiences contrasted with this view. She described feeling as if she was not recognized and was deceiving the staff: “Sometimes I imagine that I am deceiving the ward staff. Perhaps they don’t understand the problems I have because I’m so stubborn and I’m trying to take care of myself. The biggest problem, though, is my head. Anyone can be deluded” (1 month).

At the end of the year, she continued to feel as if her capabilities were being misconstrued. At this time, however, instead of feeling that the staff assumed she had too much capability she felt that they now wrongly assumed her to be incompetent in some situations. She described that when the staff ignored her statements, she felt unsure of herself stating, “I become very uncertain even though I know I’m right. My feeling is that the staff thinks that I understand less than I actually do” (12 months).

Another participant felt that his friends demonstrated a lack of recognition for – what was, clearly to him – a decrease in his contributions to their conversations. For example, he felt insufficient and left out of situations with his friends when they did not slow down their speech. In order to join in, he had to simplify the complexity of his own ideas:

“Especially when it comes to discussions, when there are two or three people and you’re discuss something. Then you want to throw something into the discussion [like] what you think. But I do not have time to formulate my thoughts. It goes far too fast [so] then I say something simpler instead. I’m not able to say what I really want to say” (12 months).

In essence, his friends were not able to recognize his struggle or his efforts.

The burden of burden

It was not easy for the participants to feel a sense of belonging, since caregiving was not only felt to be a burden for the relatives. Perceiving the burden of caregiving on their relatives burden, without being able to change the situation, the participants described how the stress of their new situation after the stroke disrupted their social world. For example, the participants could no longer share the performing of household activities. This led not only to increased responsibility and pressure for their families, but also decreased the amount of support the participants could give. As one participant recounted: “She can no longer do when I’m not the supporter behind her as I was before. So actually, I feel that it is my wife who needs the support and help all the time” (6 months).

Another participant described how the stroke had changed the whole situation for his wife and how exhausted she was after being with him at the hospital for two weeks instead taking care of the children at home: “She has been sitting there for two weeks, day and night and wasn’t able to be there for the children and such things. She looked like the living dead after not having slept in two weeks” (1 month). His wife spent her time supporting his progress: “All the time she told me what had changed and the progresses I had made” (1 month). She also treated him: “My wife massaged my arm with ointment” (1 month). His wife was not only his companion in the clinic: “She used to come in at seven in the evening” (1 month) – but outside of the clinic – also maintained their social world: “She is at home. Yes that is fortunate. Otherwise everything would collapse...” (1 month). However, this participant felt that the greatest burden for his wife was the expectation that he should live as he had held prior to the stroke.

“I don’t need to be so blasted capable. There should be no feeling that everything must be as before, because than you cause yourself a lot of problems. My wife gets a bigger burden then before. She has now got a gastric ulcer” (12 months).

He thought that all the pressure he felt to do everything now had led to her developing a gastric ulcer.

This experience carrying the caregiver burden (burden of burden) was also illustrated in another participant’s description of how his young daughter now helped to guide him around the house: “Our little daughter comes to me and says, ‘Dad, it’s not here. It’s in another direction. The toilet is out there’” (1 month). The participants also felt the burden of not being able to participate. For example, one participant could no longer join in his children’s’ activities (or tasks) as he was used to doing: “They have a hard time. I used to play with them a lot before” (3 months). This participant also felt his caregiver’s burden even without tangible evidence and recounted that: “She [his wife] doesn’t say anything, but it seems to me that she has a hard time” (3 months). This burden for his wife (during the whole year) developed into a distancing in their relationship, as he expressed it: “We have been different, you can say, a bit different. We are not as close to each other as we were before. We have become distanced” (6 months). Whether conveyed as “she got ulcers” or “we have become distanced” their descriptions did not only describe “caregiver burden” but also their experience of the burden of their caregivers’ burdens. Unable to reciprocate, it was not easy for the participants to feel that they belonged to their old social world.

Inspiration and belonging through acting with others

The participants got inspiration from “acting with” or engaging with others in activities over the year of rehabilitation. Doing something that mettered with others (16), inspired the participants to integrate into social worlds. Both at home and in the workplace, the participants’ feelings of being eased into a sense of belonging through the “collective contributions” (e.g. see 15, p. 425) of and acting with others (families, friends, colleagues).

Through acting with others, the participants were able to reflect on what really mattered in their lives, their sense of connection with others, and the abilities they would need in order to feel integrated. For example, the participants described the laborious process of re-entering their social worlds. Initially, in rehabilitation, the focus was above all on home and family. Here, they found continuity with their usual or habitual daily life, which was described by one participant as giving him more energy and inspiration:

“To have the opportunity to be home during the nights… I’m sleeping much better at home. I get better rested. It’s better when you have children and so on [so] that you can socialize a little. I’m getting more confident. We’re getting more normal routines, structure around dinner” (1 month).

The workplace was also characterized as a place to meet their colleagues, which inspired and helped them get back the feeling of having their own work and social life again.

The importance of acting together with others. The inspiration that came from engaging with others in activities emphasized how doing something with someone that matters (15) supported the participants’s sense of belonging and, thus, integration into social worlds. For example, one of the participants described how he accepted the help of a friend to take him “out into life again” after stroke, using it as an example of a strategy of rehabilitation: “Another tool is to call a friend. You need some sort of a way to move on. You need some way forward so you don’t just get stuck there…” (3 months).

Another participant exemplified how a sense of belonging to a social world of engagement was inspiring by describing her experience of attending a musical performance with her family.

“I was spending the time with my son and daughter-in-law on Saturday. Then, I was completely awake. We attended a big music spectacle [in the World Arena] and that was great even if it was a long performance and it was a bit uncertain whether I would be able to sit there for such a long time. But, no problems, and I thought it was fun the entire time. It’s easier to not have the energy when you are watching television alone. I wasn’t too tired at dinner. Rather I likely benefited from them [as] I was talking with them all the time. There were five of us” (3 months).

In contrast to her usual evenings of eating dinner and watching television alone, this sense of belonging had given her energy.

This same participant also described that what mattered for her was also that she would someday be able to initiate her own activities again as she had become more of a receiver as opposed to an initiator in her circle of friends after the stroke. Her friends could no longer expect her to take the initiative:

“It’s not like I’m taking the initiative by myself. It’s when people call me. Then I get happy and go to the countryside. But I don’t arrange anything by myself. This is missing because I was very active with this before. I’ve always been the one who has been the most active of my girlfriends. But it [the initiative] is gone. I hope it will come back, because I miss it” (12 months).

For other participants, even the experience of performing activities with other clients at the rehabilitation setting gave them a feeling of belonging that developed into inspiration to integrate further into their social worlds: “We were so close to each other as patients when staying in the ward” (3 months). After the year of rehabilitation she reflected that this was because: “All of us contributed something so you became a positive group. You have to do something fun in that situation. Perhaps it was that you got the energy to do something positive [from others]” (12 months).

Easing into belonging. Over the year of rehabilitation, the participants felt an easing into belonging that was supported by others both at home and at the workplace. For example, one of the participants described the sense of belonging she felt through being connected to her family by just being in contact and sharing the daily activities that made up her life:

“I am connected with my eldest son by always having his telephone number available. I can just press the telephone if I’m feeling bad, then my daughter-in-law is standing there making breakfast and my son is fixing something. It means everything actually, that you have someone to talk to and who, above all, calls you and cares for you” (1 month).

The importance of colleagues for a sense of belonging can be exemplified through a participant who lived alone and described his sense of loneliness and being anguished when there was a work holiday and when he could not share doing activities with his colleagues.

“This down period was mostly during the Christmas holiday when I didn’t have anything special to do. Now I’m training all day. I’m at my work. So then the weekends are rather good” (3 months).

His description over the year of going back to work, even though it continued to be part-time, began with feeling understood by his boss and colleagues: “My colleagues/friends are kind and nice. Of course, initially, I will do the work tasks I’m supposed to manage. My boss who comes on Monday [to the rehabilitation setting] is not stupid though so he understands this” (1 month). After 3 months they had begun to adjust his work tasks to his ability, making him feel that what he did really mattered and was recognized: “All of them understand what I have gone through, my bosses too. So I feel good in that way. My friends [his colleagues] give me tasks so I can feel that I’m doing something that’s not too difficult to handle” (3 months).

The shared nature of their work further eased this participant into feeling he again belonged to this social world: “It’s fun. It feels good to meet your friends again and we are all good friends. We have lunch and we talk to each other” (3 months). After 6 months, his colleagues’ recognition of his situation then led to them giving him another job that he could complete successfully: “When they were about to complete a course, then I got the task to do the form. And then, together with a girl, I laid the table. It should be done in half an hour, but it turned out well” (6 months).

At the end of the year, another colleague took over his former job and they were working at adjusting the situation to suit his ability:

“All of them understand that this is something that is not as it should be, and they’ve shown consideration for that. So it works rather well. I’m doing an easier job now than before the stroke. A friend [colleague] has taken over the job that I had before” (12 months).

Through performing activities with him, his colleagues-friends eased this participant into feeling a sense of belonging to a larger social world, in which his contributions were valued and recognized.

Workplace for social acting and support. The colleagues inspired the participants’ feeling of belonging by acting with and supporting the participants’ ability to act with them. Overall, the workplaces seemed to function as social meeting places that inspired them during the year of rehabilitation and helped the participants’ regain the feeling of having their own working and social life. Instead of being “a person on a bed” they could sit and talk during the coffee break or lunch. Even though one participant was still at the rehabilitation setting, she went back to her workplace every day to have coffee in order to maintain the social contact with her colleagues. Another participant who was asked to come to have coffee to begin experiencing his workplace again, stated “I have been talking to my boss and they asked me to come to have coffee with them…. There will be work training later on” (6 months). The colleagues were also catalysts, supporting the participants’ in gauging how they were now compared with before their stroke: “I have talked to them and asked if there is any difference compared with before. But so far nobody has said anything, [like] if I’m behaving strangely or irregularly in some way” (3 months). Another participant expressed it like this: “She used to say, ‘But now you’re starting to be as stressed as you were before. Calm down now’” (6 months).

Reality adjustment through acting with others

The participants got to know themselves in the rehabilitation process after injury through interactions with others. Through others reactions they were mirroring their own way of being and acting in their “new world” after stroke, which led to reality adjustment. The consequences of the brain injury were particularly apparent for the participants who had children. Through daily activity situations together with their children they gained reflections that led to reality adjustment. One of the participants emotionally described how, at the end of the year, his children were sad when they experienced him as another person

“They are actually getting very sad, because I’m not the same dad as before. For example, I forget things…. I have turned out to be different. I don’t know in what way, but I’m different” (12 months).

Another participant described that even though the reflections from his children were emotionally difficult in the process of reality adjustment, his children became “his tool” and inspiration in his efforts to to come back to life” as close to possible as he had been prior to the stroke:

“Your goal is to live a normal life, just as it used to be. Your children should not need to think that it is an awkward old man they are walking together with. You don’t want to deviate more than before. It’s important for oneself too” (12 months).

Participants described how family members were “interpreting each other” in daily activity situations and were finding ways of doing things together in the new life situation. For example, one of the participants described the automaticity in doing, helping him when dressing, that had developed between him and his wife: “There are many things that are functioning automatically. When I’m putting my shoes on, my wife automatically comes and ties them” (3 months). For another participant, his daughter was her father’s mirror when dressing when he was “…perhaps not buttoning it correctly [his shirt] or she was looking to see if I had pulled up my zip correctly” (3 month). Yet, new forms of connection also emerged through doing these daily activities together that, in the end, increased his sense of belonging to his family: “After a while, you interpret each other. So she understands what I mean without my needing to say anything” (3 months).

It was not only the participants themselves who were undergoing change; the whole family was going through a process of reality adjustment during the year of rehabilitation.

Discussion

Drawing from occupational and social science in which the meaning of actions in a socially constructed world is addressed (15, 16), this study focused on the meaning of acting together with others in different places during one year of rehabilitation for persons with stroke. The results of this study suggest that belonging (24) could provide this subjective frame of participation that is lacking in the ICF model (19).

The theoretical foundations for belonging draw from a range of psychological, sociological and anthropological roots, which conceptualize it as a basic individual need integral for social cohesion or citizenship and thus well-being from both individual and social perspectives (25). The concept of belonging has been suggested as a key dimension of meaning in engagement in activities (24) and has emerged as central to persons with disabilities’ perceived well-being in a range of qualitative studies (e.g. ethnographic, phenomenological, interview-based) focused on acting with others (26, 17, 27). A healing of belonging defined as “a transformation from a place of relative invisibility to one in which one receives recognition and regard as a human being” (27, p. 236) also focuses on the process of change when a person moves from a state of being perceived as disabled to one of capability consistent with the ICF (20). In this study, the experiences of belonging for persons’ with stroke were closely related to their processes of integration over one year of rehabilitation. The results of this study, then, support proposals to include subjective experiences in the concept of participation, which is in agreement with ongoing critical discussions that observations or external measures alone do not capture the complexity of “involvement in a life situation” of the ICF (26, 28–30).

A systematic review of studies of informal caregivers, including family and friends of persons with stroke, emphasizes the need for longitudinal and theoretically grounded studies related to change with more details of the experiences of both persons with stroke as well as caregivers in addition to more clarity in outcome concepts (31). Qualitative research that captures the perspectives of persons with stroke suggests the need to incorporate more than observable outcomes (26).

The results of this study showed that the participants described their new situation after stroke as “ not recognized as the person I am” and this aligns with other qualitative findings for the persons with stroke experiencing “invisibility of emotional difficulties” (1) and not “being acknowledged as individuals” (26). Yet recognition of the complexity of a person’s new situation after stroke cannot be taken for granted and may not even be possible. As Lawlor (15, p. 425) stated: “We can never know or completely understand another’s experiences, even though we have many clues and can make inferences all time”. Furthermore, collaboration with others (family, friends and colleagues) creates further challenges for rehabilitation professionals to be able to recognize a person with stroke from his or her own perspective, which requires “complex interpretative acts in which the practitioner must understand the meaning of interventions, the meanings of illness or disability in a person and family’s life, and the feelings that accompany these experiences” (32, p. 35). Thus, the significance of the shared experiences of persons with stroke, acting with other patients in rehabilitation settings and colleagues in workplaces may imply that the participants felt recognized during “…moments of meeting and the shared nature of human experience” (15, p. 426), which made them feel, to some extent, a sense of belonging to a larger social world.

As in the results of a study that showed how friends (among others) played an important role in supporting engagement in activities for persons with stroke (33), friends were also of key importance for the participants’ integration. For example, one participant described how he accepted the help of a friend to take him out to participate in life again, while another participant allowed her friends to initiate their group activities and thereby relinquished her former role. These seemed to be important acts of meaning for a sense of belonging and integration into larger social worlds.

For families and other caregivers, the study revealed that “caregiver burden” was also experienced as a burden for the persons with stroke. This finding has not previously been described in literature that focuses on the burden for relatives. This “burden of burden” was particularly heavy, as could not, or felt they could not, change the situation. Thus, the desire for a sense of belonging (e.g. a secure social context, continuity and support in helping them reorganize their new life situation) was simultaneously strained by the burden they felt they caused by their stroke. A great deal of stress and uncertainty (5) may be placed on family members after stroke that negatively affects family life (3) and/or leads to breakdowns in familiar relationship (1). However, despite the knowledge that emotional well-being has been related to perceived burden (34), little is known about the effects of “burden of burden” on the well-being of socially-occupied beings.

Despite the described feelings of connections to others through daily activities, it seemed that it was easier to feel a sense of belonging with colleagues at their workplaces than with family and friends at home or in the community even though the participants stated that the social world of engagement (34) gave them energy and meaning. The reason might be, as was shown in a study, that the desire to be reintegrated into familiar places inspired engagement in rehabilitation (10). This result is supported in this study, in which the participants stated that the support of others at their workplaces gave them a sense of belonging that, by extension, inspired them towards integration during the year-long rehabilitation process.

The doing of less threatening activities to support engagement in rehabilitation is supported by a study by Guidetti et al. (35, p. 307), which suggested that activities less linked to expectations rooted in past experiences were “harmless”. Acting with others in the workplace seemed to support persons by easing them into a sense of belonging over time. In addition, the participants’ experiences of “doing with” and sharing experiences with other clients in their rehabilitation settings could also be viewed in the context of those relationships being less threatening or “harmless” than their relationships with family members, which were rooted in past experiences and which now had the added challenge of creating a burden of burden of their caregivers.

Methodological considerations

There are some key considerations to take into account regarding the methods used in this study.

Since the data had already been collected prior to analysis, the researchers could not carry out theoretical sampling through new interviews. Instead, the theoretical sampling occurred through selecting and analysing more interviews until saturation was reached. This can be a limitation, since nuances in meaning might be lost if the researcher does not begin the analysis between interviews, and these would make it possible to follow up interesting threads in the data in the next interview.

However, the triangulation of complementary methods strengthens the findings (36). Although this study was limited by a lack of participant observations to complement the interviews, forms of triangulation were employed (34) that included discussing the rehabilitation process with the occupational therapists during data collection and obtaining feedback on the findings with an experienced research group during data analysis. The data collected by the first and third authors strengthened the validity of the analysis through case discussions and review of themes (37). Finally, at all levels of coding, the participants’ narratives were used to ground interpretation and emergent conceptualizations in order to strengthen the credibility of the results (38).

Implications for rehabilitation

Several implications for rehabilitation after stroke can be drawn from the results. The findings indicated the importance of understanding the client’s needs of belonging during rehabilitation. Rehabilitation professionals play a crucial role in supporting experiences of belonging for integration in daily life activities in different places. Results showed that others need to pay attention to recognizing the person as the person he or she was before stroke and wants to be after stroke. One way of supporting recognition might be to support feelings of competence in performing desired daily life activities (10, 35). Another implication is to ease the clients’ “burden of burden” by supporting the doing with others as caregivers or shifting the caregivers’ own burden from taking care of instrumental outcomes towards supporting the persons’ with stroke sense of belonging by “doing with”. Occupational therapists have a crucial role in supporting the families to find new and satisfying ways of doing together (39, 9, 32), which might ease the “burden of burden” perceived by the person having stroke as well as the perceived burden of others as caregivers.

The results of this study show that participants feel connected to others through doing something that matters with others in different places, which contributes to their sense of belonging, as does reality adjustment through mirroring themselves through others when performing daily activities. One implication of these results for rehabilitation of persons with stroke is that professionals should pay attention to supporting significant experiences together with others (40). By inspiring social acting with others in different places, in the rehabilitation setting, workplaces and homes, rehabilitation professionals can support the easing of persons with stroke into a sense of belonging, which is central to well-being.

AcknowledgementS

This research was funded by Vardals Foundation and Center for Caring Sciences, Karolinska Institutet. We thank the participants in the study and the rehabilitation staff who made this study possible.

References