OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of patients with burnout during a rehabilitation programme.

Patients and methods: Eighteen patients with burnout were interviewed at the end of a one-year rehabilitation programme. The programme consisted of 2 groups, one with a focus on cognitively-oriented behavioural rehabilitation and Qigong and 1 with a focus on Qigong alone. The interviews were analysed using the grounded theory method.

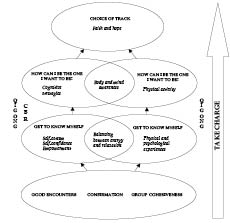

RESULTS: One core category, Take Charge, and 6 categories emerged. The core category represents a beneficial recovery process that helped the patients to take control of their lives. The common starting point for the process is presented in the 3 categories of Good encounters, Affirmation and Group cohesiveness. The categories were basic conditions for continuing development during rehabilitation. In the categories Get to know myself, How can I be the one I want to be? and Choice of track, the more group-specific tools are included, through which the patients adopted a new way of behaving.

CONCLUSION: Patients in both groups experienced group participation as being beneficial for recovery and regaining control of their lives, although in somewhat different way. An experience of affirmation and support from health professionals and group participants is of importance for behavioural change.

Key words: cognitive therapy; interviews; mind-body and relaxation techniques; Qigong; qualitative research; stress.

J Rehabil Med 2010; 42: 475–481

Correspondence address: Anncristine Fjellman-Wiklund, Department of Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiotherapy, Umeå University, SE-901 87 Umeå, Sweden. E-mail: anncristine.fjellman-wiklund@physiother.umu.se

Submitted June 26, 2009; accepted December 15, 2009

INTRODUCTION

Health complaints due to job stress are of major concern in many western countries. Twenty-two percent of workers in the European Union reported fatigue and/or stress in a 2005 survey on working conditions (1). In Sweden mental and behavioural disorders were the most common diagnoses in both women and men seeking sickness compensation in 2006 (2). A large part of this psychological ill-health has been termed burnout and attributed to workplace stressors. Burnout syndrome was not originally a diagnosis, but was defined by Maslach (3) to describe a phenomenon occurring among personnel in the human service sector. The syndrome definition was later broadened to include similar symptoms arising from stressful situations in occupations other than human services (3–6) as well as in non-working situations (5–7). In Sweden the concept of burnout syndrome has been replaced by a new diagnosis, exhaustion syndrome (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems – 10th Revision; ICD-10, F43.8A) (8), which is a broader definition of burnout and includes both occupational and non-occupational stressors.

The reference of burnout as work-related has caused interventions to be directed toward occupational settings. Factors identified as being associated with burnout are high workload, high emotional demands, and an imbalance in job demands, control and support (9). Thus, many studies have attempted to reduce stress in occupational settings (10–12). Such interventions can be applied at both the organizational and individual levels. Interventions on the individual level (e.g. relaxation techniques, meditation, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)) have been found in meta-analyses to be more efficient than organizational interventions (13–15), and interventions based on cognitive-behavioural approaches are the most effective (13, 16).

CBT is effective in treatment of depression and anxiety (17, 18) chronic fatigue syndrome (19) and, to some extent, fibromyalgia (20). However, the effects of CBT interventions on patients with burnout are fewer and the results less marked (21–24). Studies differ with regard to study populations, the definition of burnout, and the methods against which CBT is compared. Van der Klink et al. (21) studied employees who were absent due to sickness for 2 weeks because of adjustment disorder according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM IV) criteria. They found no difference in psychological symptoms between employees in a group treated with CBT combined with graded activity and a group treated with usual care, but there was a higher rate of return to work among employees in the CBT group (21).

Brattberg (22), Heiden et al. (23) and Stenlund et al. (24) included patients with different occupational backgrounds and periods of sickness absence. In Brattberg’s (21) study patients with burnout, as well as patients with chronic pain, were included. Burnout was not measured in specific, but the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (25) was used to grade the state of anxiety and depression and stress symptoms with the stress barometer. In the studies by Heiden et al. (23) and Stenlund et al. (24) the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (SMBQ) (26) was used to establish burnout. Group-based CBT was used alone (22, 23) and in combination with Qigong (24) and compared with a waiting list group (22), an exercise and a control group (23) and Qigong alone (24). Improvements were found in all studies, but there were no (23, 24) or small (22) differences between CBT and the other interventions or control groups in the studies. Symptom reduction occurs in all interventions regardless of content, so it could be questioned whether the programmes per se are effective or if other factors (such as being assessed, being asked to answer questionnaires, and other types of attention) provide the main effect.

The aim of this study was to explore patients’ experiences in a burnout rehabilitation programme with two different rehabilitation groups.

METHODS

Study design and informants

In order to capture patients’ perceptions and experiences in burnout, a qualitative approach with the grounded theory method (27) was chosen. A qualitative approach can present a holistic picture that provides a deeper understanding of how people experience and deal with complex problems. Grounded theory is proven to be a suitable method for capturing a process over a longer period.

At the end of a 1-year rehabilitation programme (24) patients with burnout were interviewed about their experiences in the programme. The programme consisted of 2 rehabilitation groups, 1 with a focus on cognitively-oriented behavioural rehabilitation (CBR) and Qigong (programme A) and 1 with focus on Qigong alone (programme B). At the time the interviews were conducted, a total of 9 groups had participated in the rehabilitation programme, 5 in programme A and 4 in programme B. The goal of this study was to interview 2 patients from each of the 9 groups. If there were more than 2 patients from a group who volunteered for participation in an interview, lots were drawn. In total, 59 patients who had completed the 1-year rehabilitation programme were asked to participate in this study. Eighteen group participants accepted, but because of a technical problem one patient was not interviewed. One patient who withdrew from programme A was also interviewed. In total, 10 women and 8 men gave informed consent and were interviewed. Ten had participated in programme A and 8 in programme B. The informants received both verbal and written information regarding the aim of the study and that their participation was voluntary and anonymous. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of Umeå University, Sweden (Umu dnr 02-311).

The age range of the informants was 31–55 years, and mean age 42.7 (SD 7.7) years for women and 45.8 (SD 6.8) years for men. The level of burnout measured with SMBQ (26) was 4.2 for women and 4.1 for men. The majority of informants had completed primary/secondary school and lived with their child/children and some other adult. Classification of their type of work was based on work title; 3 categories were used according to Kohn & Schooler (28): “with people”, “with things” and “with data”. The women worked most often “with people”, in jobs such as teacher or auxiliary nurse. The men worked most often “with data”, in jobs such as computer operator, or “with things”, including jobs such as construction worker. The mean sickness absence time when joining the 1-year rehabilitation programme was 371.1 (SD 142.2) days for women and 350.8 (SD 180.5) days for men.

Rehabilitation programme A

Programme A was a group CBR programme and consisted of 30 sessions, each one lasting for 3 h spread over 1 year and lead by a group leader specially trained in CBR. Each group consisted of 6–9 patients and there were at least 2 patients of the same sex. Every session started with 10 min of seated relaxation, followed by a specific theme. The CBR programme is described in more detail elsewhere (24). An additional 3 group meetings were held during the first year to which spouses and/or relatives were invited. There were also short follow-up meetings at 3, 6 and 12 months after the one-year rehabilitation.

In parallel with CBR, patients in programme A performed Qigong in gender-mixed groups with 12–16 patients in each, in 1-hour sessions, once a week for 1 year, supervised by a physiotherapist trained in Qigong. The Qigong programme comprised 3 parts: (i) movements for warming up; (ii) basic movements to affect body awareness, balance and coordination, breathing and muscular tension; and (iii) relaxation and mindfulness meditation. At the end of the programme, work rehabilitation support was offered to the patients. The support implied a rehabilitation meeting with the patient, the employer, the physician responsible for the patient’s medical care and the officer at the Social Insurance Agency.

Rehabilitation programme B

Patients in programme B were offered Qigong and work rehabilitation support in the same manner as in programme A. Each programme (A and B) formed separate Qigong groups.

Data collection and analyses

The informants were interviewed at the Stress Clinic, University Hospital of Umeå, where the rehabilitation programme was held. Each interview was 45–90 min long. After 17 interviews no new information on the experiences of the rehabilitation programme was obtained, thus we considered that theoretical saturation was reached. In addition, an interview was also held with one informant who withdrew from the programme, in order to obtain information from someone with experiences of not completing the programme. In total 18 interviews were held. All interviews were performed independently by 2 of the authors (AFW and CA) and the interviewers were not involved in the rehabilitation. Data were collected with open-ended questions in semi-structured interviews (29). An interview guide was used that covered themes on experiences in the rehabilitation programme, such as the informant’s own rehabilitation process during the programme, what the group meant for the informant as well as the group leader and staff at the stress clinic, and thoughts about the future. The guide was used throughout the study, but minor adjustments were made to the themes between interviews so that information provided in one interview could be taken into consideration in a following interview.

Analyses were carried out using the grounded theory method of constant comparison (27). To increase credibility, triangulation between researchers with different professional backgrounds was used (30). The study was performed by 2 authors (TS and KS), acting as group leaders in the rehabilitation programme, both of whom have extensive experiences in stress-related disease and burnout, and 2 authors (AFW and CA) outside the programme who have experience from qualitative research, occupational health and rehabilitation. In this way we had both “insider” and “outsider” perspectives. All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were read through in parts and as a whole repeatedly during the whole analysis process in order to fully understand the informants’ experiences of the rehabilitation programme. Detailed memo writing was used to capture ideas, associations and reflections related to the emerging categories. The analysis was initiated by an open coding procedure, meaning that the transcripts were read line by line and paragraph by paragraph with the objective of noting and naming important information (open codes). The open coding was performed both manually and using a freeware computer programme Open Code (Umeå University, Department of Epidemiology and the computer centre, UMDAC). The next step was selective coding, in which open codes with similar elements were compiled and categories on a more abstract level were constructed. The categories were then compared with how they related to each other (axial coding). During analysis of the categories and the connections between them a core category, which was central to all data, was identified. During all steps of the analysis each of the 4 authors independently began the coding, followed by a mutual comparison and final negotiated outcome between all authors (27).

RESULTS

The analyses resulted in the core category, Take Charge, and 6 additional categories: Good encounters, Affirmation, Group cohesiveness, Get to know myself, How can I be the one I want to be? and Choice of track. The core category represents a beneficial process for recovery that helps the informants take control of their lives. The common starting points or basis for the process for both groups are represented in the categories Good encounters, Affirmation and Group cohesiveness. These categories include the basic conditions for continued development in the rehabilitation process. The categories were intertwined; the informants were met by the group leaders, the Stress Clinic personnel and group members, they were affirmed, and developed group cohesiveness in an ongoing process. In the categories Get to know myself, How can I be the one I want to be? and Choice of track, the more specific experiences are included. The results are presented as sub-categories, categories and the core category (Fig. 1) and illustrated with quotes from the informants.

Fig. 1. The experiences of patients with burnout of participating in a rehabilitation programme. Sub-categories, categories, and the core category Take Charge, which emerged from grounded theory analysis are shown. Take Charge describes a beneficial process that helped patients to take control of their lives after being burnt-out. CBR: cognitively-oriented behavioural rehabilitation.

Take Charge

The core category Take Charge represents the point the informants had reached after one year in the rehabilitation programme and is a retrospective evaluation of the rehabilitation period. It was described as a process that was not easy to achieve but marked by ups and downs during the whole process. It started with positive encounters, affirmation and support from professionals and other patients and served as a basis for recovery. With help from professionals and other patients the informants began to reflect and they gained further insight about themselves. They also began to understand the importance of balancing their work situation, family life and the need for recovery. Through knowledge and group-specific tools, learned and practiced in both programmes A and B, the informants adopted a new way of behaving over time. The tools were important in order to counteract stressful experiences in their daily lives. When the body began to signal wellbeing, the informants began to think more actively about how to take control of their lives and their future. Some informants wanted to return to their previous work, while others decided to find another type of work. Overall the informants expressed hope for the future, but also worried about how they would manage without support from the group and professionals.

Good encounters, affirmation and group cohesiveness

Informants emphasized a good encounter at the start of the rehabilitation process. They experienced it as distinct from earlier encounters when seeking care for their symptoms. The informants had been sick-listed for a long time and had encountered many caregivers, who approached burnout patients with different treatment concepts, mainly use of medication and sick-listing. Many of the informants had been very active in demanding a referral to the Stress Clinic. They described themselves as being “seekers” or “wanderers” in the healthcare system, but now felt as if they had “come home”. The informants had great confidence in the Stress Clinic professionals and were convinced that they could obtain help there.

“It was great because it was the first time you could talk to a professional who could see this from an outside perspective, who could see me from an outside perspective and talk things through.” [Man, interview 6]

“It was a perfect encounter… I was glad, although I got a documentation saying I was sick and it’s going to take a long time…it was more or less like a death sentence, it felt like a relief afterwards… and there are others who have it like I do, …I felt very lonely before I started the programme at the Stress Clinic.” [Man, interview 7]

Some of the informants were pleased with the randomization as they wanted exactly the type of treatment they were allocated to. For example one informant did not feel comfortable with CBR and “a lot of talk” and therefore was more content with participating in the programme with emphasis on Qigong and movement. Others were dissatisfied to get “only” Qigong when they had wanted CBR. After the first period in their respective groups, the informants adjusted to the situation and were content that the assigned treatment worked well, although a preference for CBR was expressed in the Qigong group only.

The informants perceived they were treated with respect, understanding and credibility. The professionals at the Stress Clinic affirmed that they understood the informants’ symptoms and problems and they could provide explanations and hope. The explanations were experienced by the informants as an affirmation that they were “not insane”. The affirmation was even stronger when other patients in the group expressed the same type of problems and experiences.

“You believe you are going to be insane, but then you realize that is not the case, and there are others (in the group), and they seem to feel the same way, and they feel the same way, bodily and mentally, and maybe they don’t have the same type of job or…well I think it was the greatest!” [Woman, interview 4]

When informants told “their story”, other group members understood, shared the hardship and the joy and provided support and trust; in this way group cohesiveness was created and maintained. This was more evident in programme A, since the plan and structure of the programme with the specific CBR tools encouraged discussion and reflection, which together, reinforced group cohesiveness. In programme B, there was also a plan and structure represented by regular group Qigong sessions assisted by the leader. Cohesiveness developed in the group and was sometimes reinforced by spontaneous meetings before and after the Qigong sessions. Small groups were also established outside the rehabilitation programme when the patients met during their leisure time.

“We have something in common, we have this all together and we can support and help each other.” [Woman, interview 14]

Get to know myself

After some time in the programme, the informants started to reflect upon and gain insight into what had happened to them. They reflected on how and in what way they had contributed to their burnout. The informants described situations with long working hours, accepting too many assignments, and taking on too much responsibility at work and/or in family situations. They had been rushing round without listening to their bodies’ warning signals. Instead they intensified their schedules until they could no longer cope and collapsed. Given the base of support and affirmation in the groups, they became ready to scrutinize their earlier behaviours. In the group, informants received affirmation and support that helped them to gain further insight. They became aware of the importance of balancing work, family life, and the need for rest, relaxation and recovery. They also understood the need to take responsibility for their lives again and to act for change.

The experiences were common for the informants of both programme A and B, although the ways in which they gained insight varied. Informants from programme A learned cognitive tools (other ways to think) and worked on their self-esteem, self-confidence and empowerment. Through group discussions on certain themes they discovered what roles they had taken on or been given in relationships. They discovered the behavioural patterns that led to burnout. Informants from programme B used physical and psychological experiences from the Qigong movements as tools, such as deep breathing to calm themselves and body scanning in order to handle stress reactions. The level of insight varied among the informants. Some had come further in the process than others and had a higher readiness for change, while others relied on the group leaders’ suggestions for change.

“I have had a lot of help from all these exercises but most of all from the exercise, and I do it often, the one where you stand in front of the mirror and tell yourself, every day, that you are good enough as you are.” [Woman, interview 4]

“…and then I have methods to relax…I have never been able to relax, it was never on my mind, I either slept or worked.” [Man, interview 6]

How can I be the one I want to be?

This step in the rehabilitation process could be described as the embodiment of mental insights. With the help from tools learned and practiced in the respective programmes, informants started to recognize how the body’s signals were related to daily activities and feelings. Through careful practice of the new ways to behave, with the body as a reference, they started to change their way of prioritizing, learned to set boundaries, and adopted new behaviours. Both groups used tools that reflected the interaction between body and mind. Practices did not always work out well and then the group support became even more important as some informants perceived a lack of support from families, friends and work-mates.

The informants in programme A used mostly cognitive strategies for change and for breaking their old behavioural patterns. They worked less and spent more time on themselves and with family and friends who allowed formation of good relationships.

“When you decide to stop doing certain things…you feel much calmer, what a relief, now I have decided this, now I am going to do what I have been thinking of doing and the rest I’ll do some other day. It feels great.” [Woman, interview 13]

For informants in programme B, positive effects were expressed in terms of body’s sensations from movements. By using breathing exercises and calming movements they experienced relaxation and a positive tiredness. These positive experiences from movements of the body could also evoke interest in more physical activity, as was expressed by some informants. That led to a chain of positive reactions, with better sleep, less pain, more energy and a greater ability to concentrate. Together, this gave a feeling of increased well-being. However, some informants experienced difficulty in complying with exercising at home. In these situations the positive effects were short-lived.

Interviewer: “You showed an example (of an exercise)…taking a deep breath?”

Informant: “Yes I do it every day, many times a day… because now, when I feel stressed I notice it right away; it is very good for me.” [Man, interview 16]

“No, I don’t do Qigong, but on the other hand I do physical exercise 3 times a week, and I didn’t do that before. If it’s a result of the Qigong I don’t know, but I feel fine being a little stronger, getting a bit more strength in the arm muscles and from that I am in better shape and maybe I have fewer heart problems.” [Woman, interview 12]

Behavioural change was not expressed as easy to achieve, but rather as a constant balancing between new and old habits including a necessity to resist expectations from other people. The body and self-esteem had to be strong in order to choose the new track in life. When the informants felt well and the body signals were good, they were affirmed being on the “right track”. That served as a basic condition for choosing a future track.

“Today I feel the signals from the body in a totally different way. You…you are much more conscious about what’s happening and what to do about it. In a totally different way…But most of all I have totally new values…and what I learned is that I am no perpetual motion machine. Because, I have learned to value other things as important, it’s not important to get the best job and…to travel a lot…and to see everything…in relation to…my personal values…I, as a private person, am much more important today than me performing a work task if you understand what I mean.” [Man interview 13]

Choice of track

The category Choice of track describes thoughts about the future. The informants expressed joy for life as well as faith and hope for their futures. At the same time they had a humble attitude towards the future, based on their traumatic experiences. They felt strengthened by the rehabilitation programme and yet afraid and worried about how to cope without the group when the programme finished. The informants expressed willingness to return to work. Some of them wanted to return to their ordinary work, while others were more doubtful about returning to work as they perceived that it had caused their burnout. However, they were positive about working with “something else”.

“My goal is to start with labour practise this autumn, in September or October, about that, that is my goal.” [Woman, interview 8]

“I have tried to get to know myself as a person, what I am being stressed over, and to avoid that. I have changed my way of behaving and my way of living to feel better…I think I have come a long way. It feels…I feel fine today compared with a year ago. I feel as if it’s going to work out fine; the only thing is for the future, if there’s a down period or if something happens to your family that makes it go downwards, that could make you fall back again.” [Man, interview 7]

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study explores the experiences of patients with burnout in a rehabilitation programme using CBR combined with Qigong or Qigong alone. The results show that patients in both groups experienced participation in the programme as beneficial for their recovery, although in somewhat different ways. The whole rehabilitation process with its core category, Take Charge, represents the patients’ general perceptions centred on taking control of their own lives and focusing on the future. The patients in both programmes aimed at adopting a new way of behaving through programme-specific tools, with the body as practise ground. There were ups and downs in the process. When the patients learned to listen to the body’s signals and received positive reinforcement in the form of enhanced well-being, they were able to take charge of their situations. Improvements in psychological variables have also been found in the RCT-evaluations of the programme (24).

The patients’ perception of the rehabilitation as an ongoing process has also been found in studies describing multimodal cognitive treatment programmes for people with stress-related and/or musculoskeletal disorders (31, 32). Both studies found similar descriptions as in our study of how the patients took control of their lives by recognizing stress-symptoms in stressful life situations and of how they developed new strategies to handle these situations. Eriksson et al. (31) described “taking control of everyday life” as a part of the rehabilitation process, while Bremander et al. (32) considered “changing one’s life plan” to be the overall rehabilitation process. According to Bullington et al. (33) the rehabilitation process for chronic pain patients after a successful rehabilitation programme was expressed as a “desire to and capacity to take charge of their life situation”.

In our study self-esteem and self-confidence were important to develop the new strategies to handle situations of stress, especially to the patient in the programme combining CBR and Qigong. This is in line with what Eriksson et al. (31) found on how patients with stress-related symptoms changed their self-image after a rehabilitation programme with a cognitive behavioural approach, resulting in new strategies to handle stress. Bremander et al. (32) instead used the concepts self-efficacy and self-insight when describing the overall life changes in the rehabilitation process for chronic pain patients. In addition to the cognitive strategies, the patients in both programme A and B used the body’s signals, to raise self-awareness and set limits. The embodiment of knowledge achieved during the rehabilitation process enabled them to take control of their lives even though they continued to have some worries about their ability to manage. Through a body-oriented therapy, rigid patterns of behaviour, thinking and feeling can be released on a non-verbal level (33). Through listening to the body’s signals and being mindful the patients were able to put their experiences into words and thus restored integration of body and mind. It could be argued that some of the underlying concepts for the programme-specific tools in CBR and Qigong in our study are of the same eastern origin and traditions although accomplished in different ways. This has been expressed as “western psychology meets eastern philosophy” (34). This may explain why CBR focusing on the mind and Qigong on the body can result in similar perceptions. Qigong as a method has ancient eastern roots and can be considered as movement meditation. Through calm movements and breathing a person can learn how to stay in contact with the body’s signals, to be in the present and to steer thoughts towards a calm mind.

Being met initially in a positive and affirming way was experienced as a necessary starting point for recovery in our study. This was expressed by patients in both rehabilitation groups. For many of the patients it was the first time they perceived that they had encountered expert knowledge conveyed in a respectful and trustful way by professionals, and this created confidence and faith in the future. Affirmation is considered as a base for building trust between people and a help when trying to solve problems. It creates closeness and optimism. When we affirm others and ourselves we create “good circles” with the environment (34). Our findings are supported by a study showing that patients need to be treated with respect and empathy and a tolerant attitude in order to achieve a successful rehabilitation (31). Support from health professionals for providing information and generating knowledge are important as well as learning new tools from different professionals (32). In our study affirmation and perceived support from other patients was expressed as a further base for recovery by patients in both groups. Programme-specific tools learned during the rehabilitation were emphasized as important in order to counteract experiences in stress in all day life. This implies that affirmation and support alone would not have had the same effect, at least not as secondary prevention. Being part of a group gives the patients possibilities to identify themselves with others in the same situation, to share experiences, to learn from others in a similar situation, and may also help patients to understand their situation in a different way (31, 32, 35). For patients with the same specific disorder, only a person in a similar situation can be fully aware of and understand the experience of another patient (35). Thus, to give support to other members of a group seems to be as crucial as receiving support from group members.

Methodological considerations

To increase the credibility of our findings, we used triangulation between researchers (30) with different professional backgrounds. Triangulation between methods was not used in this paper, but was used in the overall project on rehabilitation of burnout patients (24) of which this paper is a part. The prolonged engagement and “insider perspective” is represented in the study by the 2 group leaders (TS and KS) with in-depth knowledge of the rehabilitation programme and the informants. The “outsider perspective” was represented by the 2 interviewers (CA and AFW) who did not know the informants but knew of the rehabilitation programme and the work of the Stress Clinic. A possible limitation is that the informants may have said certain things that they thought the researchers wanted to hear. After 17 interviews, new data did not add more information; thus we considered that we had reached theoretical saturation, based on a subjective decision. In order to reflect experiences from patients who did not complete the rehabilitation programme, a patient who withdrew from the programme A was interviewed. The basic conditions, positive encounters, affirmation and support were also experienced by that informant.

In order to collect complete data all interviews were audio-taped and transcribed. Peer-debriefing was used. All 4 of the investigators took an active part in the coding process. Memo writing was used throughout the whole analysis process for capturing ideas, associations and reflections. Coding and categorization was first made independently, followed by mutual comparison and a final negotiated outcome to reach the core category (27). Semi-structured interviews as a method for collecting data proved suitable for capturing experiences important to the informants. The informants in this study corresponded well to the mixed group of patients in the rehabilitation programme at the Stress Clinic. In this study patients were referred to the Stress Clinic, assessed for study eligibility and voluntarily accepted participation in the interviews. Thus, any generalizations must be made with great care. Our findings might also be valid for other patients with burnout or stress-related ill-health. A study carried out in a context similar to the one described here has shown similar results (31), thus supporting our findings.

In conclusion, rehabilitation programmes consisting of CBR combined with Qigong or Qigong alone in group sessions provide tools that patients can use in their recovery and to regain control of their lives. An experience of affirmation and support from healthcare professionals and group participants is of importance at the start of behavioural change.

REFERENCES