OBJECTIVE: To determine bias due to loss of participants (attrition bias) in a prospective cohort study.

DESIGN: A multi-centre prospective cohort study.

SUBJECTS: A total of 225 individuals with a spinal cord injury from 8 Dutch rehabilitation centres.

METHODS: Participants were considered non-participants when no information was collected at the measurement one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Using bivariate tests participants and non-participants were compared regarding personal, lesion, function and functional characteristics determined at the beginning of inpatient rehabilitation and at discharge. A logistic regression was performed to determine which characteristics predict participation at one year after discharge.

RESULTS: Of the participants at the start of the study, 31% (n = 69) did not perform the tests one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Variables associated with study participation one year after discharge were: higher level of education, higher well-being score at the start of rehabilitation, and a shorter length of stay in hospital and rehabilitation centre at discharge of inpatient rehabilitation.

CONCLUSION: Selective attrition in the longitudinal study might have led to an over-estimation of some of the results of the measurement one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation.

Key words: spinal cord injuries, rehabilitation, prospective studies, follow-up studies, patient dropouts.

J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 382–389

Correspondence address: Sonja de Groot, DNO, Revalidatiecentrum Amsterdam, Overtoom 283, NL-1054 HW Amsterdam, The Netherlands. E-mail: s.de.groot@fbw.vu.nl

Submitted April 24, 2008; accepted November 26, 2008

INTRODUCTION

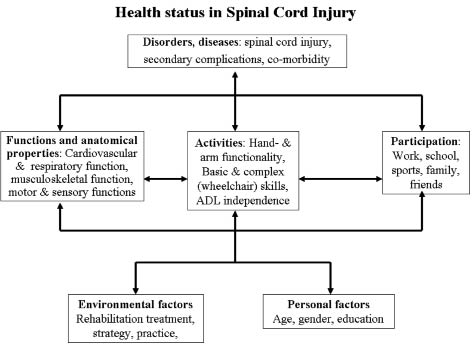

The Dutch prospective cohort project “Restoration of mobility in spinal cord injury rehabilitation” is a multi-centre longitudinal cohort study conducted in 8 rehabilitation centres with specialized spinal cord injury (SCI) units (1). The theoretical relevance of this cohort study is to improve our understanding of recovery of mobility at the levels of function and structure, activity and societal participation, and the relationships between these levels. Each domain of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model (2) is represented by several (sets of) outcome measures (Fig. 1). To study restoration of mobility, a wide variety of physical tests and questionnaires were administered to recently injured patients with SCI at the start and discharge of inpatient rehabilitation and one year after discharge.

A problem in all longitudinal studies is loss of participants to follow-up, i.e. the response rate decreases between the first measurement and the follow-up assessments (3, 4). In our prospective cohort project 225 persons were included at the start of rehabilitation; however, at the last measurement (one year after discharge), only 156 persons performed the tests. This might lead to attrition bias, when the participants who participated in the last measurement are systematically different from those who did not (4). This potential attrition bias has not yet been evaluated in our prospective cohort study, but might be very important for 2 reasons. Firstly, since attrition will most likely occur in future longitudinal rehabilitation studies, it is important to gain more insight into the factors that determine whether participants attend on recurring test occasions. Knowing which factors play a role might enable researchers to minimize loss of follow-up. Secondly, it is important to investigate differences between participants and non-participants at the measurement one year after rehabilitation, because it might influence the results and generalizability of the conclusions of this cohort study.

Since the outcome variables of the Dutch cohort study concerned all domains of the ICF model, possible differences between participants and non-participants one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation also need to be investigated for all ICF domains. For example, participants with a higher level of education might return to work (domain societal participation) earlier (5) and, therefore, might not be able or motivated to return to the rehabilitation centre for a research project. This could lead to an under-representation of persons returning to work at the measurement one year after discharge. Another possibility is that persons with a more severe SCI (domain health disorder), leading to more physical strain during daily activities, might not be able to travel to the rehabilitation centre to perform all the tests one year after discharge. Based on the population actually measured, the results of the domain function and activities may then be too positive at one year after discharge.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to investigate: (i) possible differences in characteristics related to personal (age, gender), health disorder (lesion level, completeness, cause, secondary complications, length of stay), function (forced expiratory flow, muscle strength), activity (Functional Independence Measure (FIMTM), wheelchair skills) and societal participation (education, work, living situation, well-being) at the start and discharge of inpatient rehabilitation between participants and non-participants at the measurement one year after inpatient rehabilitation, and (ii) which of these determinants predict participation at one year after discharge.

METHODS

The current prospective cohort study was part of the Dutch research programme “Physical strain, work capacity and mechanisms of restoration of mobility in the rehabilitation of persons with SCI” (1). The main purpose of the prospective cohort study was to investigate the course of restoration of mobility during and one year after SCI rehabilitation and to study possible determinants of this course. Persons were included in 8 rehabilitation centres that are specialized in SCI rehabilitation in The Netherlands. Participants were eligible to enter the project if they had an acute SCI, were between 18 and 65 years of age, were classified as A, B, C or D on the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment scale (6), did not have a progressive disease or psychiatric problem, and had sufficient understanding of the Dutch language to understand the purpose of the study and the testing methods. Since restoration of mobility in most people with SCI means using a wheelchair, only subjects who were, at least in part, wheelchair-dependent were included.

All tests and protocols were approved by the medical ethics committee. After they had been given information about the testing procedure, all participants completed an informed consent form.

Design

Data for the current study were collected at the start of active rehabilitation when the participant could sit in a wheelchair for at least 3 h, at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, and one year after discharge. Data were collected by trained research assistants with a paramedic background using standard procedures and equipment.

Outcome measure and determinants

The outcome of interest was the actual study participation at the measurement one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Discriminative analyses and a prognostic model were used to examine whether there were determinants for participation at the measurement one year after discharge. There were 2 reasons to use the determinants described below: (i) the whole of the determinants should cover each level of the ICF model (2) as do the measured variables of the prospective cohort study (Fig. 1); (ii) data from tests and questionnaires had to be available for most participants (i.e. preferably questionnaire data or tests that were performed by all participants) at the start and discharge of inpatient rehabilitation. The definition of the determinants was similar to that used in previous studies from the prospective cohort study (1, 5, 7, 10, 11, 20).

Fig. 1. (Sets of) outcome measures in the Dutch cohort study for the different domains and contexts of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model as were among others evaluated in the Dutch cohort study. ADL: activities of daily living.

Domain personal factors. Participant information regarding age, gender and level of education was collected at the start of rehabilitation. Education level was classified as low (no or only lower (vocational) education), middle (high school) or high (bachelor/master) (5).

Domain disorders, diseases. Lesion characteristics (level and completeness) were determined at each test occasion using the ASIA standard neurological classification of SCI (6). The cause of the lesion (traumatic vs non-traumatic) was registered at the start of rehabilitation. Time since injury was calculated at the start of inpatient rehabilitation, representing duration of hospitalization. In the Netherlands patients with SCI are transferred from the hospital to the rehabilitation centre and do not stay in a nursing home in between. Time since injury was also calculated at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, reflecting the total duration of hospitalization and inpatient rehabilitation.

Based on the participant’s history and medical chart, the physicians registered each complication (pressure sores, respiratory infection, urinary tract infection) on a standardized list (7). At the start of active rehabilitation, complications then present or that had occurred since admission to rehabilitation were registered. At discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, complications then present or that had occurred over the last 3 months were registered. The occurrence of a complication was registered as follows: 0 = no complication; 1 = one or more complications are or were present (7).

Domain function. To assess respiratory function, flow-volume curves were prepared with an Oxycon Delta (Jaeger, Hoechberg, Germany). The forced expiratory flow/sec (FEV1) (in l) for each participant was expressed as a percentage of the expected score for that participant in comparison with an age-, sex-, and height-matched able-bodied population (8).

To determine the strength of the upper extremities, the shoulder abductors, internal and external rotators, elbow flexors and extensors, and wrist extensors in both arms were tested with the manual muscle test (MMT). This test was performed in standardized positions, in which participants performed a movement either with gravity eliminated, against gravity, or against resistance (9). Strength was rated on a scale ranging from 0 to 5 (9). Summing the scores of the 12 muscle groups gave an MMT sum score (maximum 60).

Domain activities. The level of independence in activities of daily living was assessed with the use of the motor score (13 items) of the FIMTM (10). Each item is scored on a 7-point scale, with 7 indicating complete independence and 1 total dependence. The FIM motor score is the sum of the score on the 13 items (maximum 91).

From an established wheelchair performance test that has 8 tasks (described in detail by Kilkens et al. (11)), 2 tasks were selected for the present study to reflect wheelchair propulsion: figure-of-eight and 15 m sprint. The performance time score, which is the sum of the time needed to perform the figure-of-eight and the 15 m sprint as fast as possible, was calculated.

Domain societal participation. Paid work status before SCI (1 = work; 0 = no work) was determined at the start of rehabilitation as 1 of the elements of societal participation. Furthermore, it was asked at the start of rehabilitation whether participants were living alone or with others (e.g. partner, family, friends). The Utrechtse Activiteiten Lijst (12) was used to assess the time spent on vocational and leisure activities, such as work, study, voluntary work, hobbies and sports activities, in h/week. This questionnaire is a Dutch adaptation of the Craig Handicap Assessment Rating Technique (13).

A question about the person’s overall life satisfaction (“What is at this moment your opinion regarding your quality of life?”) was included at each test occasion. This question was rated on a 6-point scale: very unsatisfying, unsatisfying, rather unsatisfying, rather satisfying, satisfying and very satisfying. This score was dichotomized (unsatisfied: 1–4 vs satisfied: 5–6) according to Fugl-Meyer et al. (14).

Statistics

Scores at the start and discharge of inpatient rehabilitation of participants and non-participants at the measurement one year after inpatient rehabilitation were compared using independent samples t-tests (parametric data) and Mann-Whitney U tests or χ2 tests (non-parametric data). Differences in participation between centres were analysed with a Kruskal-Wallis test (p < 0.05). There were 2 groups of non-participants: those who were not willing or able to participate (drop-outs, Table I); and those who, for several reasons, were not invited any longer (Table I). To investigate differences between these 2 groups and the participants a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test was performed.

Possible predictors of not participating at the measurement one year after discharge were studied using a logistic multi-level random coefficient analysis, which can correct for differences between rehabilitation centres. Separate models were made for independent variables at the start and at discharge of inpatient rehabilitation. The dependent variable was study participation one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation (0 = non-participants; 1 = participants). The independent variables at the start of rehabilitation and/or discharge were added separately to the model to study their individual relationship with study participation one year after discharge. The independent variables were: age (years), gender (male = 0; female = 1), time since injury (months), type of injury (traumatic = 0, non-traumatic = 1), lesion level (tetraplegia = 0; paraplegia = 1) and completeness (complete = 0; incomplete = 1), secondary complications (≥ 1 complications = 0; no complications = 1), %FEV1, MMT sum score, FIM motor score, wheelchair performance time, education (dummy 1: low vs middle; dummy 2: high vs middle), work before the injury (no = 0; yes = 1), vocational and leisure participation pre-injury (h per week), and quality of life (unsatisfied = 0; satisfied = 1). Independent variables with p-values ≤ 0.1 were included in a subsequent multivariate model in which a backward selection procedure was followed, excluding non-significant determinants (p > 0.05), in order to create the final multivariate model.

The regression coefficients for the determinants were converted to odds ratios (ORs). An OR of 1 indicated that there was no association between the independent variable and study participation one year after discharge, a significant OR > 1 indicated an increased chance of study participation one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, whereas a significant OR < 1 indicated that participants with that characteristic were less likely to participate in the study.

RESULTS

Loss to follow-up

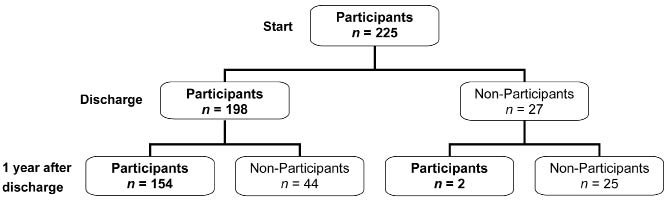

Out of the total of 225 persons who participated at the start of active rehabilitation, 198 (88%) participated at discharge of inpatient rehabilitation and 156 (69%) performed the tests one year after discharge (Fig. 2). Reasons for not participating in the study one year after discharge varied; for example, some persons were deceased, others moved away or refused to collaborate further (Table I). Without counting those persons who were excluded by the researchers, i.e. who were no longer invited (n = 11 at discharge and n = 13 at one year after discharge (Table I)), participation rates would have been 198 / (225–11) = 93% and 156 / (225–11–13) = 78%, respectively.

| Table I. Reasons for not performing the measurement one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation classified in 5 categories: (1) deceased, (2) refusal/did not attend, (3) could not be reached, (4) organizational reasons, (5) excluded during the study |

| | Non-participants at discharge (n) | Non-participants one year after discharge (n) | Participants one year after discharge (n) | Total |

| Participants one year after discharge | 0 | 0 | 1561 | 156 |

| Reasons for non-participation one year after discharge |

| Drop-outs | | | | |

| 1. Deceased | 5 | 6 | 0 | 11 |

| 2. Refusal | 81 | 16 | 0 | 22 |

| Did not attend at appointment | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 3. Transferred/moved | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Could not be reached | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Not invited | | | | |

| 4. Contract research assistant ended | 1 | 8 | 0 | 9 |

| 5. Can walk again | 8 | 4 | 0 | 12 |

| Psychiatric problems after the start of rehabilitation | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 27 | 44 | 156 | 225 |

| 12 of these participants did not participate at discharge but came back one year after discharge. |

Fig. 2. Participants and loss to follow-up in the Dutch prospective cohort study (1).

Participants vs non-participants

Table II shows score distributions of the independent variables at the start and discharge of inpatient rehabilitation for the participants and non-participants one year after discharge. The percentage of non-participants varied from 15% to 50% between centres. A significant difference was found between centres (p = 0.046) for participants and non-participants one year after discharge.

| Table II. Descriptive characteristics at the start and discharge from inpatient rehabilitation of the participants and non-participants one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation (n = 225)1 |

| Variable | Non-participants, n = 69 | Participants, n = 156 | |

| n | % or mean (SD) | n | % or mean (SD) |

| Personal characteristics |

| Age, years | | 67 | 42.2 (14.2) | 155 | 39.8 (14.0) | 0.25 |

| Gender | | | | | | |

| men | | 55 | 81 | 112 | 72 | 0.18 |

| women | | 13 | 19 | 43 | 28 | |

| Disorders, diseases |

| Cause of injury | | | | | | |

| traumatic | | 47 | 69 | 117 | 76 | 0.33 |

| non-traumatic | | 21 | 31 | 38 | 24 | |

| Lesion level at start | | | | | | |

| tetraplegia | | 30 | 44 | 55 | 36 | 0.23 |

| paraplegia | | 38 | 56 | 100 | 64 | |

| Lesion level at discharge | | | | | | |

| tetraplegia | | 25 | 42 | 47 | 35 | 0.42 |

| paraplegia | | 34 | 58 | 86 | 65 | |

| Completeness at start | | | | | | |

| complete | | 40 | 62 | 110 | 71 | 0.21 |

| incomplete | | 25 | 38 | 45 | 29 | |

| Completeness at discharge | | | | | | |

| complete | | 40 | 71 | 79 | 61 | 0.24 |

| incomplete | | 16 | 29 | 50 | 39 | |

| Complications at start | | | | | | |

| 0 complications | | 23 | 34 | 56 | 36 | 0.88 |

| ≥ 1 complications | | 44 | 66 | 98 | 64 | |

| Complications at discharge | | | | | | |

| 0 complications | | 16 | 37 | 68 | 46 | 0.38 |

| ≥ 1 complications | | 27 | 63 | 81 | 54 | |

| Time since injury atstart, days | | 61 | 110.7 (66.2) | 141 | 104.3 (62.9) | 0.51 |

| Time since injury at discharge, days | | 54 | 385.2 (187.6) | 148 | 316.7 (159.7) | 0.01 |

| Function | | | | | | |

| FEV1 at start, % | | 51 | 72.2 (24.2) | 130 | 72.3 (24.3) | 0.98 |

| FEV1 at discharge, % | | 38 | 81.4 (19.9) | 141 | 82.6 (21.5) | 0.77 |

| MMTsum at start | | 52 | 48.4 (16.1) | 129 | 51.5 (12.8) | 0.18 |

| MMTsum at discharge | | 38 | 52.0 (14.3) | 143 | 54.1 (11.0) | 0.33 |

| Activities | | | | | | |

| FIMTM at start | | 65 | 41.8 (18.8) | 150 | 40.7 (19.1) | 0.68 |

| FIMTM at discharge | | 41 | 63.0 (24.0) | 150 | 64.0 (20.6) | 0.79 |

| Performance time at start | | 38 | 30.8 (12.6) | 101 | 30.8 (18.2) | 0.99 |

| Performance time at discharge | | 34 | 21.6 (7.2) | 129 | 23.0 (12.5) | 0.53 |

| Societal participation | | | | | | |

| Education | | | | | | |

| low | | 21 | 33 | 52 | 36 | 0.10 |

| middle | | 29 | 45 | 45 | 31 | |

| high | | 14 | 22 | 48 | 33 | |

| Work pre-injury | | | | | | |

| work | | 59 | 87 | 128 | 83 | 0.55 |

| no work | | 9 | 13 | 27 | 17 | |

| Living situation pre-injury | | | | | | |

| alone | | 14 | 21 | 41 | 27 | 0.40 |

| with others | | 53 | 79 | 112 | 73 | |

| Utrecht Activity List, h | | 66 | 67.3 (20.0) | 152 | 67.5 (18.3) | 0.93 |

| Well-being at start | | | | | | |

| unsatisfied | | 52 | 81 | 104 | 70 | 0.09 |

| satisfied | | 12 | 19 | 45 | 30 | |

| Well-being at discharge | | | | | | |

| unsatisfied | | 24 | 60 | 76 | 52 | 0.37 |

| satisfied | | 16 | 40 | 71 | 48 | |

| 1 Data were not possible to obtain from all patients. SD: standard deviation; FEV1: forced expiratory flow per second; FIMTM: Functional Independence MeasureTM; MMTsum: manual muscle test sum score. |

Independent t-tests showed (p = 0.01) only one difference between participants and non-participants, i.e. non-participants had a longer length of stay in hospital and rehabilitation centre at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation compared with participants (Table II).

The final logistic random coefficient models showed that the loss to follow-up was related only to level of education, life satisfaction at the start of rehabilitation and length of hospitalization and inpatient rehabilitation (Tables III and IV). Participants with a higher level of education were 2.2–2.8 times more likely to attend at the measurement one year after inpatient discharge than participants with a middle level of education. Those persons who were satisfied with their life at the start of active rehabilitation were 2.3 times more likely to attend one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, while those who had a one month longer length of stay for inpatient rehabilitation were 0.93 times less likely to attend one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation.

| Table III. Results of the final multi-level logistic random coefficient model with the outcome variable participants (= 1) vs non-participants (= 0) and the association with significant independent variables measured at the start of active rehabilitation |

| | Beta (SE) | Odds | 95% CI | p |

| Constant | 0.249 (0.254) | | | |

| | | | | |

| Education dummy 1 | 0.586 (0.368) | 1.79 | 0.87–3.70 | 0.11 |

| Education dummy 2 | 0.800 (0.391) | 2.23 | 1.03–4.79 | 0.04 |

| | | | | |

| Well-being at start | 0.785 (0.394) | 2.30 | 1.01–4.75 | 0.04 |

| Education dummy 1: low (1) vs mid (0) level of education; Education dummy 2: mid (0) vs high (1) level of education. Well-being: unsatisfied (0) and satisfied (1); SE: standard error; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. |

| Table IV. Results of the final multi-level logistic regression model with the outcome variable participants (= 1) vs non-participants (= 0) and the association with significant independent variables measured at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation |

| | Beta (SE) | Odds | 95% CI | p |

| Constant | 1.350 (0.410) | | | |

| Education dummy 1 | 0.578 (0.392) | 1.78 | 0.83–3.84 | 0.14 |

| Education dummy 2 | 1.010 (0.445) | 2.75 | 1.15–6.57 | 0.02 |

| Time since injury at discharge (months) | –0.070 (0.029) | 0.93 | 0.88–0.99 | 0.02 |

| Education dummy 1: low (1) vs mid (0) level of education; Education dummy 2: mid (0) vs high (1) level of education; SE: standard error; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. |

When the non-participants were divided into drop-outs and persons who were not invited, and compared with the participants on all 25 variables, a few differences were found (Table V). The group drop-outs consisted of more men and more persons with a non-traumatic injury compared with the other groups. The drop-outs showed the lowest %FEV1 at the start of rehabilitation in contrast to the not invited persons who showed the highest %FEV1. The group of persons who were not invited had the highest percentage of “unsatisfied” scores on the life satisfaction question at the start of active rehabilitation. Both the drop-out and not-invited groups had a longer time since injury at discharge of inpatient rehabilitation compared with the participants.

| Table V. Descriptive statistics and statistical differences between the non-participants (divided into drop-outs and those who were not invited to participate) and the participants at the measurement one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation1 |

| Variable | Non-participants | Participants | p |

| Drop-outs | Not invited |

| n (%) | Mean (SD) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | n (%) | Mean (SD) |

| Gender | | | | | | | | |

| men | | 40 (89) | | 15 (65) | | 112 (72) | | 0.04 |

| women | | 5 (11) | | 8 (35) | | 43 (28) | | |

| Cause of injury | | | | | | | | |

| traumatic | | 27 (60) | | 20 (87) | | 117 (76) | | 0.04 |

| non-traumatic | | 18 (40) | | 3 (13) | | 38 (25) | | |

| Well-being at start | | | | | | | | |

| unsatisfied | | 31 (74) | | 21 (96) | | 104 (70) | | 0.04 |

| satisfied | | 11 (26) | | 1 (4) | | 45 (30) | | |

| Time since injury discharge, days | | 37 | 388.8 (170.5) | 17 | 377.4 (225.8) | 148 | 317.7 (159.7) | 0.04 |

| FEV1 start, % | | 31 | 65.4 (21.1) | 20 | 82.7 (25.4) | 130 | 72.3 (24.3) | 0.04 |

| 1 Data were not possible to obtain from all patients. SD: standard deviation; FEV1: forced expiratory flow per sec. |

DISCUSSION

Loss to follow-up

The percentage of participants who were lost between the start of active rehabilitation and discharge from inpatient rehabilitation or one year after discharge was 12% and 31%, respectively. In several longitudinal studies among people with SCI the loss to follow-up differed from 13% when measuring health-related outcome one year after discharge (15), to 21% in a study assessing functional skills one year after discharge (16), and even to 43% (35% could not be reached and 8% were no longer willing to participate) in a survey study with a 1.5-year follow-up (17). Loss to follow-up in the SCI model systems database was 15%, 36% and 51% for 1, 5 and 10 post-injury years, respectively, but this is loss to follow-up of medical care, which is expected to be lower than loss to follow-up in research (18). Compared with the results of these studies, our loss to follow-up seems to be not unusual for research in the SCI rehabilitation field. From a theoretical viewpoint, assuming that the non-participants are not missing at random, but would be more likely to drop out, a loss to follow-up of as little as 20% is suggested to lead to serious problems (4). Therefore, it is very important to achieve the maximum possible follow-up rate.

When we summarized the actual reasons for not participating (Table I), the non-participants could be divided into 2 groups: those who were no longer willing to participate (drop-outs) and those who were not invited to participate due to several reasons (not invited). The group drop-outs consisted of more men, more persons with a non-traumatic lesion and with a worse lung function (i.e. lower %FEV1). The latter factor might indicate a lower physical capacity and, therefore, might lead to refusal to participate because it costs too much effort or due to participants being deceased.

Participants who became walkers were more frequently excluded during inpatient rehabilitation, while after rehabilitation more participants were not measured because they refused to participate, could not be reached, or the research assistant was not able to test the participant again. The difference between centres regarding loss to follow-up is partly due to unavailability of a research assistant in one centre during part of the study. Of course, the ability to motivate or persuade the participants to participate in the follow-up measurements, which is a very important factor for continued inclusion, might also be an explanation for the difference between the centres, as well as the distance of the centre from the participant’s home environment. The assessment for research did not coincide with regular clinical follow-up. In the Netherlands there is no standardized aftercare follow-up programme. Assessment in all centres was the same, i.e. around one year after discharge of inpatient rehabilitation.

Participants vs non-participants

It is important not only to know how many persons are lost to follow-up (drop-outs as well as those not invited) but also whether this group is systematically different on key characteristics from the group that participated in the measurement one year after inpatient discharge. This might lead to attrition bias in the study results.

Of all outcome measures used in the current study, only duration of hospitalization and inpatient rehabilitation, level of education, and life satisfaction at the start of active rehabilitation were related to study participation at the measurement one year after discharge. Those people who had a longer stay in hospital and rehabilitation centre were less likely to participate in the measurement one year after rehabilitation. Length of stay is associated with the severity of the lesion and the occurrence of complications (10). However, lesion level and complications were not associated with participation at the measurement one year after discharge. After a long stay in the hospital and rehabilitation centre it is likely that individuals are glad to be living at home again and, due to possible negative associations, may be less motivated to return to the rehabilitation centre (for a research project).

Those people who had a lower life satisfaction score at the start of active rehabilitation were less likely to participate one year after discharge. A higher percentage of people who were not invited to participate (e.g. walkers, persons with psychiatric problems) had low life satisfaction scores compared with the drop-outs and participants. All those people who were able to walk had an incomplete SCI. Worse mood scores in people with incomplete SCI compared with those with complete SCI have been reported previously (19). Most of the walkers and those with a psychiatric problem were already excluded during rehabilitation, which might explain why life satisfaction at discharge was not related to study participation one year after discharge.

Since life satisfaction at the start of active rehabilitation (20) and length of stay (10) are related to the level of the lesion, it was surprising that lesion level was not related to study participation in the measurement one year after discharge. The outcome measures in the domains function and activity were also not related to study participation one year after discharge. Furthermore, a selected population, only those who were wheelchair bound, were included, and this may also influence the absence of an association with the level of the lesion.

Level of education was related to study participation in the measurements one year after discharge when analysed with the multi-level random coefficient analysis (Tables III and IV) in contrast to the less powerful bivariate analysis (Table II). Persons with a higher level of education were 2.7 more likely to return to the rehabilitation centre for the measurement. This result was in agreement with previous studies (21, 22), which found that responders reported a higher frequency of education beyond high school (84%) when first surveyed than non-responders (73%) (21), and that responders reported more years of education (22). However, this is in contrast to the lack of significant association between loss to follow-up and education found in the Model Systems spinal cord injury database (18). These different findings might be explained by the fact that the Models System Database consists of data recorded during regular medical care compared with data that were collected in research projects. A lower level of education is associated with the risk of re-admission (23), because those unaware of the importance of leading a healthy lifestyle and maintenance of health may be more at risk of complications requiring readmission. People with a higher education might be more aware of the importance of research and health maintenance and, therefore, might be more motivated to participate.

Implications for the Dutch cohort study

The question that needs to be answered is what are the implications of the above-mentioned results for future analyses of the Dutch prospective cohort study and for the interpretation of current reports? Krause & Coker (22) found that, compared with the non-responders, their responders were younger, were more likely to have cervical injuries, reported more years of education, greater satisfaction with health, greater sitting tolerance, and more frequent social outings. Lin et al. (18) showed that patients who were retired or unemployed, or had less severe neurological deficit were more likely to be lost to follow-up, while no significant association was found between loss to follow-up and age, race, sex, education and marital status. No attrition bias was found in the present study for important personal and lesion characteristics, such as age, gender, level and completeness of the lesion. From the 16 possible characteristics or outcome measures that might lead to attrition bias in the current study only life satisfaction, length of stay and education were different between the participants and non-participants. As we found only one significant difference in 25 bivariate analyses and 3 significant predictors in 25 multi-level analyses, these significances might also be chance findings due to multiple testing.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is missing data due to forms not being completed fully or because not all participants were able to perform the tests, e.g. the wheelchair skill circuit.

Furthermore, the difference between participants and non-participants was only tested with outcome measures that were available for most participants. Some of these test scores have a ceiling effect (e.g. the sum score of the manual muscle strength test), which might have made it more difficult to find a difference between the participants and non-participants.

Persons who have only completed the questionnaires at home or via an interview by telephone at the measurement one year after discharge were also assigned to the participant groups, although they were not willing to return to the rehabilitation centre for performing the physical tests. These persons might differ from those who actually returned to the centre for the measurement one year after discharge. A subdivision was made of the non-participators, into those who were missing at random (drop-outs), a factor that we cannot influence, and those who were excluded by the researchers, a factor that we can influence. Subdividing the non-participants into more groups would have been interesting; however, the groups would be very small (e.g. n = 5 who could not be reached). For that type of investigation, larger subject groups are necessary.

At present, participants in the Dutch cohort study are invited to return to the rehabilitation centres for a measurement 5 years after discharge. When the data from this follow-up measurement have been collected, possible attrition bias should be investigated again.

In conclusion, the Dutch longitudinal SCI cohort study experienced attrition bias due to loss to follow-up of participants who had a lower life satisfaction score at the start of rehabilitation, a lower level of education, and a longer length of stay in hospital and rehabilitation centre compared with persons who participated one year after discharge. These results may lead to an over-estimation of the results on the ICF domains personal factors (education), disorders and diseases (longer length of stay) and societal participation (life satisfaction) at the measurement one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Future longitudinal studies should attempt to achieve the maximum possible follow-up rate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the 8 participating rehabilitation centres and especially the research assistants for collecting all the data: Sacha van Langeveld (De Hoogstraat, Utrecht), Annelieke Niezen/ Peter Luthart (Rehabilitation Center Amsterdam), Marijke Schuitemaker (Het Roessingh, Enschede), Karin Postma (Rijndam Revalidatiecentrum, Rotterdam), Jos Bloemen (Hoensbroeck Revalidatiecentrum, Hoensbroek), Hennie Rijken (Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen), Ferry Woldring (Beatrixoord, Haren) and Linda Valent (Heliomare, Wijk aan Zee).

Funding: this study was supported by the Dutch Health Research and Development Council, ZON-MW Rehabilitation programme, grant numbers 1435.0003 and 1435.0025.

REFERENCES