Won Hyuk Chang, MD, PhD1, Min Kyun Sohn, MD, PhD2, Jongmin Lee, MD, PhD3, Deog Young Kim, MD, PhD4, Sam-Gyu Lee, MD, PhD5, Yong-Il Shin, MD, PhD6, Gyung-Jae Oh, MD, PhD7, Yang-Soo Lee, MD, PhD8, Min Cheol Joo, MD, PhD9, Eun Young Han, MD, PhD10, Jeong Hyun Kim, OT1 and Yun-Hee Kim, MD, PhD1

From the 1Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Center for Prevention and Rehabilitation, Heart Vascular and Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, 2Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, School of Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, 3Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Konkuk University School of Medicine, 4Department and Research Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, 5Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, 6Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Pusan National University School of Medicine, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Busan, 7Department of Preventive Medicine, Wonkwang University School of Medicine, Iksan, 8Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, 9Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Wonkwang University School of Medicine, Iksan and 10Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Jeju National University Hospital, University of Jeju School of Medicine, Jeju, Korea

OBJECTIVE: To investigate the return to work status of patients with first-ever stroke with functional independence 6 months post-stroke.

DESIGN: Prospective cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS: Nine hundred and thirty-three patients with functional independence at 6 months after stroke onset.

METHODS: A complete post-enumeration survey was performed through a review of the medical records for first admission. In addition, structured self-administered questionnaires and a face-to-face interview were performed assessing occupational status, quality of life, and emotional status at 6 months after stroke.

RESULTS: Of the patients in this study, 60.0% returned to work at 6 months after stroke. Sex, age, educational level, and comorbidity level were independent factors related to return to work. The rate of return to work in female patients under 65 years of age was similar to that of male patients 65 years of age or older. Stroke patients who returned to work showed better emotional statuses than those who did not return to work.

CONCLUSION: Many stroke patients did not return to work despite functional independence at 6 months after stroke. Based on the results of this study, we suggest providing appropriate vocational rehabilitation for stroke patients and proper education for employers to increase the rate of early return to work in stroke patients.

Key words: stroke; return to work; occupation; vocational rehabilitation; functional independence; quality of life.

J Rehabil Med 2016; 48: 273–279

Correspondence address: Yun-Hee Kim, Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Center for Prevention and Rehabilitation, Heart Vascular and Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, 50 Ilwon-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul 135-710, Republic of Korea. E-mail: yunkim@skku.edu, yun1225.kim@samsung.com

Accepted Nov 10, 2015; Epub ahead of print Feb 4, 2016

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is one of the most common causes of adult disability in Korea and worldwide (1, 2). Although the management of stroke in the acute stage has improved greatly, most post-stroke care will continue to rely on rehabilitation (3). In many stroke rehabilitation strategies, a common goal is to reduce stroke-related impairment and disability (3). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Under this definition, the ultimate goal of stroke rehabilitation should be to improve a patient’s quality of life. In patients with traumatic brain injury, employment is an essential part of daily living, affecting social integration, health status, and quality of life (4). Considering the importance of employment, return to work (RTW) can be considered one of the main outcome goals of rehabilitation and treatment in stroke patients with functional independence (5).

Vocational rehabilitation (VR) has been recommended to improve the rate of RTW in patients with stroke (6, 7). Although VR is beneficial for increasing social well-being, many chronic patients show a tendency to receiving a disability pension rather than RTW (8). The first step for successful VR is the establishment of proper inclusion criteria. To select candidates for VR, the RTW status should be investigated in patients with stroke. There have been a few studies on the influence of RTW on the quality of life of patients with stroke (8, 9). The level of activities of daily living, cognitive function, and ambulatory function are known to be factors affecting RTW in patients with stroke (8). From a practical point of view, RTW cannot be considered in all stroke patients. Therefore, stroke patients with functional independence could be good candidates for VR. However, no study has reported the status of RTW in stroke patients with functional independence.

This study investigated the status of RTW in patients with first-time stroke and functional independence at 6 months after the stroke. In addition, the influence of RTW on psychosocial outcomes, including quality of life, is reported at 6 months post-stroke. This paper aims to provide suggestions for establishing effective VR for patients with stroke.

METHODS

Korean Stroke Cohort for Functioning and Rehabilitation

The Korean Stroke Cohort for Functioning and Rehabilitation (KOSCO) is a cohort of first-time acute stroke patients who were admitted to participating hospitals in 9 distinct areas of Korea (10). The KOSCO, designed as a 10-year long-term follow-up study of stroke patients, is a prospective multi-centre project investigating the factors that influence residual disabilities, activity limitations, and long-term quality of life in patients who have had a first-time stroke. The recruitment of first-time stroke patients began in August 2012 and is still ongoing. Data were collected during acute inpatient treatment in all patients aged 19 years or older who were admitted to 1 of the participating hospitals within 7 days after their first stroke. Both ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes were included, but transient ischaemic attacks were excluded.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to inclusion in the study, and the study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee in each hospital.

Selection of participants

This study presents the interim results of the KOSCO for evaluating the functional levels of first-time stroke patients at 6 months after onset. The data at 6 months after stroke onset in patients (n = 3,007) who were recruited to the KOSCO from August 2012 to October 2014 were analysed. Inclusion criteria were: (i) functional independence at 6 months with a Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (11) score of more than 120; (ii) normal cognitive function at 6 months with a Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) (12) score of more than 25; and (iii) complete independent ambulatory function with a Functional Ambulatory Category (FAC) (13) score of 5. These inclusion criteria were based on the related functional factors contributing to RTW reported by a previous study (14). Among the included patients, we analysed the data in patients who were working before their strokes.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

A complete enumeration survey of all patients was performed at first admission. Survey items included demographic data, such as age, sex, education, marital status and employment. Comorbidity level was assessed using combined condition and age-related score in the Charlson comorbidity index (CCAS, lower score is better), which is commonly used to measure patients’ comorbid conditions (15). Initial stroke severity was recorded at the time of hospital arrival, using the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (range: 0–42, lower score is better) (16) and the Glasgow Coma Scale (range: 3–15, higher score is better) (17) for ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes, respectively. Functional performance prior to the index event was assessed with the modified Rankin scale (range: 0–6, lower score is better) (18). In addition, details of the first admission course of all patients, including presentation to the rehabilitation department, inpatient rehabilitation treatment, transfer to the rehabilitation department, and discharge destination, were recorded.

Assessment of occupation at 6 months after stroke

Patients completed self-administered questionnaires about occupation history, such as status and classification of occupation before stroke, and status and classification of occupation at 6 months after stroke. Additional questionnaires about the details of the occupation change were carried out in patients with RTW.

The occupational classification followed the major groups of the Korean Standard Classification of Occupations (KSCO) (19). The KSCO was based on the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-88). The major groups are: senior officials and managers, professionals and associated workers; clerical workers; service workers; sales workers; skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers; craft and related trades workers; plant or machinery operators and assemblers; elementary occupations; and armed forces occupations. Homemaker was not included as an occupation.

Functional assessment at 6 months after stroke

Functional evaluations were performed using face-to-face functional assessment, including FIM for independence of activities of daily living, K-MMSE for cognitive function, and FAC for mobility and gait.

Structured self-administered questionnaires at 6 months after stroke

Patients completed structured self-administered questionnaires and underwent a face-to-face interview. All patients were invited to visit our research centre for functional assessment batteries, structured self-administered questionnaires, and face-to-face interviews. If patients were not able to visit our research centre, these same investigations were performed at their homes. Structured self-administered questionnaires and a face-to-face interview consisted of the Geriatric Depression Scale – Short Form (GDS-SF) (20) for depressive mood, Euro Quality of Life (EQ)-5D (21) for quality of life, Psychosocial Well-being Index – Short Form (PWI-SF) (22) for subjective health conditions, Reintegration to Normal Living Index (RNLI) (23) for the degree of return to a normal life, and Family Support Index (FSI) (24) for the patients’ subjective feelings of familial support. The GDS-SF and PWI-SF are worse with higher scores, while the EQ-5D, RNLI, and FSI are better with higher scores.

Statistical analysis

All participants were divided into a RTW group and a no-RTW group according to their RTW status at 6 months post-stroke. In addition, the prevalence of RTW by sex and age less than 65 years were calculated separately. An independent t-test was undertaken for normally distributed continuous variables to compare between the RTW and no-RTW groups. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. To assess the related factors for RTW, we used a multiple logistic regression model to estimate the association (odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI)) between the RTW status and sex, current age, educational level, marital status, comorbidity level, and premorbid functional level. p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0.

RESULTS

Study population and demographic and clinical characteristics

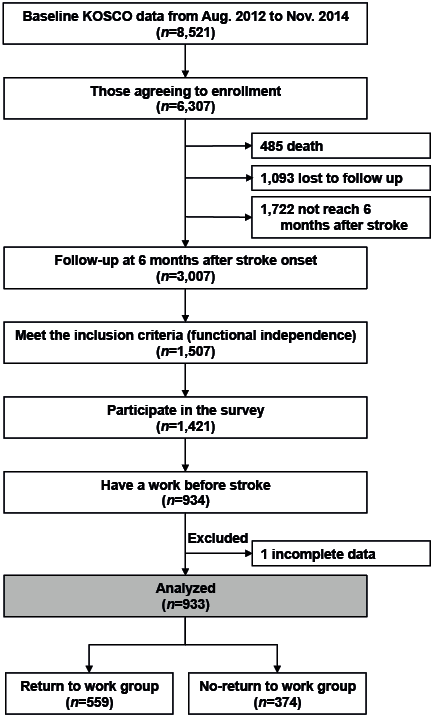

Between August 2012 and October 2014, 8,521 patients provided informed consent to participate in the follow-up study, with a participation rate of 78.3% of the patients assessed for eligibility in the 9 participating hospitals in Korea. The number of patients who met the inclusion criteria was 1,507, from among 3,007 patients who were followed up at 6 months. Thus, 50.1% of stroke patients showed functional independency at 6 months after onset. Of the patients who completed the 6-month follow-up, 1,421 participated in the survey and 934 were working before their strokes. Of these 934 patients, 1 was excluded because of missing information. Therefore, a total of 933 first-time stroke patients were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

The basic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table I. Their mean age was 56.99 years, and 77.1% were male. There were 721 (77.3%) patients with an ischaemic stroke, and 212 (22.7%) patients with a haemorrhagic stroke.

Return to work status

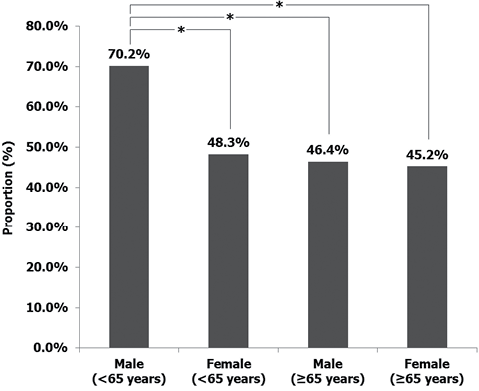

At 6 months post-stroke, 560 patients (60.0%) who had an occupation before their strokes showed RTW. Stratified by age and sex, male patients less than 65 years of age showed a significantly higher rate of RTW than the other 3 groups (p < 0.05, Fig. 2). Among these 560 patients, 16 (2.9%) reported a change in occupation at 6 months post-stroke, while 544 (97.1%) reported a return to the same workplace.

Fig. 2. Rates of return to work, stratified by age and sex.*p < 0.05 comparison between groups.

According to the KSCO, skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers and professionals and associated workers were the occupations that showed the highest rate of RTW. On the other hand, RTW to armed forces occupations and elementary occupations had the lowest rates among stroke patients at 6 months post-stroke. Stratified by age and sex, professionals and associated workers had the highest rate of RTW in both male and female patients less than 65 years of age. Skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers had the highest rate of RTW in male and female patie-nts who were 65 years of age or older (Table II).

Relating factors for return to work

In comparison with the no-RTW group, the proportion of patients who were male and had haemorrhagic strokes were significantly higher in the RTW group (p < 0.05). Age and comorbidity levels as measured by the CCAS in the RTW group were significantly lower than in the no-RTW group (p < 0.05). In addition, education level in the RTW group was significantly higher than in the no-RTW group (p < 0.05, Table I).

|

Table I. Comparison of baseline characteristics between return to work (RTW) and no-RTW groups |

||||

|

Characteristics |

Total |

RTW group |

No-RTW group |

p-value |

|

Participants, n |

933 |

560 |

373 |

|

|

Demographics, % |

|

|

|

|

|

Male |

77.1 |

81.8 |

70.0 |

< 0.001* |

|

Age |

|

|

|

< 0.001* |

|

18–34 years |

3.1 |

3.2 |

2.9 |

|

|

35–44 years |

12.4 |

14.6 |

9.1 |

|

|

45–54 years |

26.7 |

29.6 |

22.3 |

|

|

55–64 years |

32.3 |

32.9 |

31.4 |

|

|

≥ 65 years |

25.5 |

19.7 |

34.3 |

|

|

Educational level, % |

|

|

|

< 0.001* |

|

None |

5.5 |

4.8 |

6.4 |

|

|

Primary education |

9.3 |

9.1 |

9.7 |

|

|

Middle school education |

16.4 |

14.5 |

19.3 |

|

|

High school education |

37.3 |

33.2 |

43.4 |

|

|

University education |

31.5 |

38.4 |

21.3 |

|

|

Marital status (Married) |

88.5 |

88.2 |

88.8 |

0.831 |

|

Comorbidity level (CCAS), % |

|

|

|

0.006* |

|

No comorbidity (0–1) |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

Mild comorbidity (2–3) |

17.4 |

19.1 |

14.7 |

|

|

Moderate comorbidity (4) |

24.6 |

27.1 |

20.9 |

|

|

Severe comorbidity (5–) |

58.0 |

53.8 |

64.4 |

|

|

Premorbid functional level (mRS), % |

|

|

|

0.083 |

|

0 |

68.1 |

70.2 |

64.9 |

|

|

1 |

14.5 |

15.0 |

13.7 |

|

|

2 |

7.6 |

7.3 |

8.0 |

|

|

3 |

1.9 |

1.3 |

2.9 |

|

|

4 |

5.6 |

4.5 |

7.2 |

|

|

5 |

2.3 |

1.7 |

3.3 |

|

|

Stroke subtype, % |

|

|

|

0.017* |

|

Ischaemic stroke |

77.3 |

80.0 |

73.2 |

|

|

Haemorrhagic stroke |

22.7 |

20.0 |

26.8 |

|

|

Initial severity, % |

|

|

|

|

|

Ischaemic stroke (NIHSS) |

|

|

|

0.361 |

|

Very mild (0–2) |

42.4 |

37.9 |

45.0 |

|

|

Mild (3–4) |

22.3 |

21.7 |

22.7 |

|

|

Moderate (5–15) |

28.1 |

32.5 |

25.5 |

|

|

Severe (16–42) |

7.2 |

7.9 |

6.8 |

|

|

Haemorrhagic stroke (GCS) |

|

|

|

0.007* |

|

Mild (14–15) |

75.6 |

81.5 |

68.8 |

|

|

Moderate (9–13) |

17.4 |

16.7 |

18.3 |

|

|

Severe (3–8) |

7.0 |

1.8 |

12.9 |

|

|

Initial stroke management |

|

|

|

|

|

REH consult, Yes, % |

71.4 |

70.7 |

72.4 |

0.580 |

|

REH transfer, Yes, % |

10.7 |

7.0 |

16.4 |

< 0.001* |

|

Hospitalization, days, mean (SD) |

12.8 (13.2) |

10.4 (9.6) |

16.4 (16.6) |

< 0.001* |

|

Discharge destination, % |

|

|

|

0.118 |

|

Home |

88.8 |

90.5 |

86.3 |

|

|

REH specialized clinic or hospital |

6.4 |

5.2 |

8.1 |

|

|

Other clinic or hospital |

4.8 |

4.3 |

5.6 |

|

|

*p < 0.05 between the RTW and no-RTW groups. CCAS: combined condition and age-related score in the Charlson comorbidity index; mRS: modified Rankin scale; NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; REH: rehabilitation department. |

||||

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that sex, age, educational level, and comorbidity level were independent relating factors for RTW in stroke patients at 6 months (Table III). In particular, male sex, an age of 35–54 years, university educational level, and a mild-to-moderate comorbidity level were strong relating factors for RTW (Table II).

|

Table II. Proportion of return to work stratified by sex and age according to the Korean Standard Classification of Occupations (KSCO) |

||||||

|

Occupational classification |

Total % (n/n) |

Age (< 65 years) |

|

Age (≥ 65 years) |

||

|

Male (n = 523) % (n/n) |

Female (n = 172) % (n/n) |

|

Male (n = 196) % (n/n) |

Female (n = 42) % (n/n) |

||

|

Senior officials and managers |

60.0 (33/55) |

62.2 (23/37) |

50.0 (2/4) |

|

58.3 (7/12) |

50.0 (1/2) |

|

Professionals and associated workers |

62.4 (58/93) |

80.0 (36/45) |

53.6 (15/28) |

|

36.8 (7/19) |

0.0 (0/1) |

|

Clerical workers |

57.3 (106/185) |

71.1 (86/121) |

43.3 (13/30) |

|

21.2 (7/33) |

0.0 (0/1) |

|

Service workers |

57.6 (80/139) |

65.4 (53/81) |

44.4 (16/36) |

|

60.0 (9/15) |

28.6 (2/7) |

|

Sales workers |

58.0 (51/88) |

75.9 (22/29) |

53.8 (21/39) |

|

50.0 (7/14) |

16.7 (1/6) |

|

Skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers |

66.4 (85/128) |

77.8 (28/36) |

35.7 (5/14) |

|

65.5 (38/58) |

70.0 (14/20) |

|

Craft and related trades workers |

57.4 (62/108) |

65.0 (52/80) |

37.5 (3/8) |

|

33.3 (6/18) |

50.0 (1/2) |

|

Plant or machinery operators and assemblers |

52.7 (29/55) |

62.2 (28/45) |

0.0 (0/4) |

|

20.0 (1/5) |

0.0 (0/1) |

|

Elementary occupations |

51.8 (29/56) |

63.6 (21/33) |

50.0 (4/8) |

|

28.6 (4/14) |

0.0 (0/1) |

|

Armed forces occupations |

36.4 (4/11) |

57.1 (4/7) |

– (0/0) |

|

0.0 (0/4) |

– (0/0) |

|

No response |

46.7 (7/15) |

55.6 (5/9) |

0.0 (0/1) |

|

50 (2/4) |

0.0 (0/1) |

|

Change of occupation, n |

16 |

9 |

4 |

|

3 |

0 |

|

n/n: number of patients before stroke/number of patients at 6 months post-stroke; KSCO: Korean Standard Classification of Occupations. |

||||||

|

Table III. Odds ratios (OR) for factors associated with return to work |

||

|

Factors |

OR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

Male sex |

0.519 (0.381–0.706) |

< 0.001 |

|

Age |

|

< 0.001 |

|

18–34 years |

1.904 (0.862–4.205) |

0.111 |

|

35–44 years |

2.806 (1.747–4.509) |

< 0.001 |

|

45–54 years |

2.327 (1.613–3.358) |

< 0.001 |

|

55–64 years |

1.830 (1.297–2.583) |

0.001 |

|

≥ 65 years |

1 |

|

|

Educational level |

|

< 0.001 |

|

None |

0.413 (0.225–0.759) |

< 0.001 |

|

Primary education |

0.521 (0.316–0.857) |

0.004 |

|

Middle school education |

0.413 (0.275–0.622) |

0.010 |

|

High school education |

0.422 (0.302–0.589) |

< 0.001 |

|

University education |

1 |

|

|

Marital status, married |

1.399 (0.697–1.617) |

0.177 |

|

Comorbidity level (CCAS) |

|

0.006 |

|

Mild comorbidity (2–3) |

1.551 (1.075–2.238) |

0.019 |

|

Moderate comorbidity (4) |

1.554 (1.127–2.143) |

0.007 |

|

Severe comorbidity (5–) |

1 |

|

|

Premorbid functional level (mRS) |

|

0.093 |

|

0 |

1.949 (0.829–4.579) |

0.126 |

|

1 |

1.976 (0.797–4.903) |

0.142 |

|

2 |

1.640 (0.627–4.293) |

0.314 |

|

3 |

0.764 (0.215–2.708) |

0.676 |

|

4 |

1.111 (0.409–3.021) |

0.836 |

|

5 |

1 |

|

|

CCAS: combined condition and age-related score in the Charlson comorbidity index; mRS: modified Rankin scale; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. |

||

Influence of return to work

The EQ-5D and RNLI were significantly higher in the RTW group than in the no-RTW group (p < 0.05). In addition, the GDS-SF and PWI-SF were significantly lower in the RTW group than in the no-RTW group (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in FSI.

Stratified by age and sex, the male stroke patients under 65 years of age in the RTW group showed significantly higher EQ-5D, RNLI, FSI scores and lower GDS-SF and PWI-SF scores (p < 0.05). In addition, the male stroke patients over 65 years of age in the RTW group showed significantly higher EQ-5D and RNLI scores and lower GDS-SF scores (p < 0.05). However, the EQ-5D, GDS-SF, PWI-SF, RNLI, and FSI showed no significant differences between the RTW and no-RTW groups in female stroke patients (Table IV).

|

Table IV. Comparison of quality of life and emotional characteristics between the return to work (RTW) and no-RTW groups |

||||||

|

Variables |

RTW group |

|

No-RTW group |

p-value |

||

|

Median (IQR) |

Mean (SD) |

|

Median (IQR) |

Mean (SD) |

||

|

Total (n = 933) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EQ-5D |

0.9500 (0.0370)* |

0.9171 (0.0577)* |

|

0.9130 (0.0800) |

0.8922 (0.0770) |

< 0.001 |

|

GDS-SF |

2.0 (4.0) * |

3.6 (3.5)* |

|

4.0 (6.0) |

5.1 (3.7) |

< 0.001 |

|

PWI-SF |

11.0 (14.0) * |

12.3 (9.4)* |

|

15.0 (14.0) |

15.6 (10.0) |

< 0.001 |

|

RNLI |

100.0 (2.7) * |

96.4 (9.1)* |

|

100.0 (11.8) |

91.6 (13.7) |

< 0.001 |

|

FSI |

48.0 (11.0) |

47.2 (7.1) |

|

47.0 (11.0) |

46.4 (7.9) |

0.149 |

|

Male age < 65 (n = 523) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EQ-5D |

0.9500 (0.0370)* |

0.9214 (0.0516)* |

|

0.9130 (0.0800) |

0.8867 (0.0826) |

< 0.001 |

|

GDS-SF |

2.0 (3.0)* |

3.2 (3.4)* |

|

4.0 (5.0) |

5.1 (3.8) |

< 0.001 |

|

PWI-SF |

11.0 (14.0)* |

11.4 (9.1)* |

|

15.0 (11.0) |

16.7 (10.2) |

< 0.001 |

|

RNLI |

100.0 (0.0)* |

96.9 (9.0)* |

|

100.0 (11.8) |

91.7 (13.8) |

< 0.001 |

|

FSI |

48.0 (10.0)* |

47.4 (7.1)* |

|

47.0 (12.3) |

45.7 (9.4) |

0.042 |

|

Female age < 65 (n = 172) |

||||||

|

EQ-5D |

0.9130 (0.0430) |

0.9088 (0.0715) |

|

0.9130 (0.0430) |

0.9070 (0.0574) |

0.854 |

|

GDS-SF |

4.0 (6.0) |

4.3 (4.0) |

|

4.0 (6.0) |

5.2 (3.8) |

0.113 |

|

PWI-SF |

15.0 (16.0) |

14.2 (9.9) |

|

15.0 (16.0) |

14.9 (9.4) |

0.660 |

|

RNLI |

98.2 (10.9) |

94.9 (10.6) |

|

98.2 (10.9) |

92.6 (11.1) |

0.152 |

|

FSI |

47.0 (10.0) |

44.6 (7.8) |

|

47.0 (10.0) |

46.3 (6.9) |

0.060 |

|

Male age ≥ 65 (n = 196) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EQ-5D |

0.9500 (0.0430)* |

0.9153 (0.0615)* |

|

0.9130 (0.0800) |

0.8959 (0.0712) |

0.042 |

|

GDS-SF |

3.0 (3.0)* |

3.8 (3.1)* |

|

4.0 (5.0) |

4.8 (3.5) |

0.035 |

|

PWI-SF |

13.0 (15.5) |

12.9 (8.9) |

|

13.0 (16.0) |

14.0 (10.1) |

0.434 |

|

RNLI |

100.0 (5.5)* |

96.0 (7.5)* |

|

100.0 (12.7) |

91.4 (14.5) |

0.005 |

|

FSI |

50.0 (10.0) |

48.1 (6.1) |

|

46.0 (11.0) |

46.6 (6.4) |

0.112 |

|

Female age ≥ 65 (n = 42) |

||||||

|

EQ-5D |

0.8700 (0.1330) |

0.8792 (0.0710) |

|

0.8700 (0.1330) |

0.8564 (0.1126) |

0.449 |

|

GDS-SF |

6.0 (7.0) |

6.6 (4.2) |

|

4.0 (7.0) |

5.4 (4.0) |

0.352 |

|

PWI-SF |

19.0 (13.0) |

18.5 (11.1) |

|

17.0 (12.0) |

17.0 (9.9) |

0.652 |

|

RNLI |

96.4 (9.1) |

93.4 (8.9) |

|

96.4 (25.5) |

87.8 (18.3) |

0.207 |

|

FSI |

52.0 (8.0) |

49.5 (7.0) |

|

48.0 (9.0) |

47.6 (5.3) |

0.335 |

|

*p < 0.05 compared with the no-RTW group. EQ-5D: Euro Quality of Life-5D; GDS-SF: Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form; PWI-SF: Psychosocial Well-being Index-Short Form; RNLI: Reintegration to Normal Living Index; FSI: Family Support Index; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation. |

||||||

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the rate of RTW was 60.0% in patients with functional independence 6 months post-stroke. The factors related to RTW at 6 months in stroke patients with functional independence were sex, age, educational level, and comorbidity level. Patients under 65 years of age with an occupation in the professionals and associated worker category prior to their strokes were more likely to return to work more easily than patients in other occupations. Patients over the age of 65 years with an occupation in the skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery worker category prior to their strokes showed the highest rate of RTW. Male stroke patients with RTW showed a better quality of life and emotional status than those without RTW. In female stroke patients, there appeared to be no definite difference in quality of life and emotional status according to RTW. These results revealed the prevalence, relating factors, and influence of early RTW in stroke patients in Korea, which could be used to establish more effective VR for stroke patients.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of RTW among stroke patients in Korea. The rate of RTW can differ by country, culture, and compensation policy (25). Compared with a previous study with similar methodology, the rate of RTW in this study paralleled the outcomes of survivors of mild-to-moderate strokes in the USA (26). Occupations with higher RTW rates were senior officials and managers, professionals and associated workers, and skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers. These may be occupations that are more similar to self-employment. One inclusion criterion of this study was working prior to the stroke, resulting in a population that had the ability to work before stroke. In addition, we included stroke patients with functional independence and normal cognitive and mobility function. Even with these inclusion criteria, the difference in the rate of RTW between patients in self-employed and hired occupations could be due to negative opinions of stroke patients by employers. Therefore, proper education for employers is needed to improve RTW in stroke patients.

Factors relating to RTW in this study were consistent with those identified in patients with acquired brain injury (14). This suggests that the factors relating to RTW in patients with strokes and in patients with traumatic brain injury could be pooled. We analysed the RTW status according to sex and age, which are non-modifiable factors. The RTW status showed a significant difference according to sex and age group. A low rate of RTW in working-age individuals could increase the indirect costs of stroke (26). The rate of RTW was highest in male patients under 65 years old, while the rate of RTW in female patients under 65 years old was similar to that of male and female patients 65 years of age or older. Addressing the lower rate of RTW in female patients under 65 years old could be important for reducing the costs of stroke. In particular, there were lower rates of RTW in all occupation classifications of female patients compared with their male counterparts under 65 years of age. Based on these results, female patients under 65 years of age should be especially considered for RTW.

This study found that stroke patients with RTW had better emotional status than those without RTW. This suggests that RTW could influence quality of life and emotional status in stroke patients with functional independence. In addition, this is consistent with previous studies on patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage (9) and traumatic brain injury (4). Therefore, employment may be an essential part of quality of life in patients with stroke. However, these quality of life and emotional statuses according to RTW were different according to analyses stratified by age and sex. In male stroke patients, RTW could influence quality of life and depressive mood, as well as the degree of return to a normal life. In particular, male stroke patients under 65 years of age showed better subjective health conditions and feelings for family in the RTW group. These results might be due to cultural expectations in Korea, that males of working age generally have responsibilities for generating an income and supporting family members (27). RTW in male stroke patients can be considered an important goal in stroke rehabilitation. Therefore, this population are proper candidates for VR. There was no significant difference in the quality of life and emotional status in female stroke patients with RTW. These differences between sexes might be due to the exclusion of homemaker as an occupation in this study, as well as cultural differences.

With increasing life expectancy, retirement age has been increasing, and extending working lives has become an important policy focus for many governments (28). Therefore, we analysed the data for stroke patients who were working prior to the stroke regardless of age. In addition, the male stroke patients over 65 years of age in the RTW group showed significantly higher EQ-5D and RNLI scores and lower GDS-SF scores. These results mean that RTW might influence psychosocial outcomes even in elderly male patients with stroke. However, there is a lack of previous research about the work status and its influence on psychosocial levels in elderly persons. Further study is required into this topic.

In this study, the RTW group had significantly shorter durations of hospitalization than the no-RTW group. In general, duration of hospitalization may be an indicator of stroke severity or severity of medical complications after stroke onset (4). Thus, medical complications during the first hospitalization might be more severe in the non-RTW group. However, this did not influence the results of this study, as there was no significant difference in functional level between the 2 groups at 6 months. Some patients without RTW could return to work after this evaluation at 6 months after stroke onset. In addition, some patients with RTW could retire from their job at 6 months after stroke onset. Further study will be needed to investigate long-term work status in stroke patients.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the inclusion criteria were relatively narrow. Because the inclusion criteria included functional independence and normal cognitive and mobility function, this study could not demonstrate the status of all stroke patients. Another limitation is that we could not distinguish between full-time and part-time work, or between the patient being an employer or an employee. In addition, mental fatigue and social support are known to be factors influencing RTW in stroke patients with functional independence (29). Unfortunately, we could not assess these potential influencing factors on RTW in this study, which is a limitation. A more detailed survey of work status could yield a better analysis of RTW in stroke patients. Despite these limitations, we were able to perform functional evaluations and interviews face-to-face rather than by telephone. This approach is one of the study’s strengths, increasing the likelihood that the findings are valid.

In conclusion, this study revealed that many stroke patients could not return to work despite functional independence and normal cognitive and mobility function at 6 months after stroke onset. Based on the results of this study, we suggest that appropriate VR and the proper education of employers could increase the rate of early RTW in stroke patients. Male stroke patients under 65 years of age could be the most suitable candidates for VR. In addition, social support may be needed to improve RTW in female stroke patients under 65 years of age.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013E3301702) and the NRF grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (NRF-2014R1A2A1A01005128).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES