Karin C. M. van Weert, MD1,2, Evert J. Schouten, MD1, José Hofstede, MD2, Henk van de Meent, MD, PhD3, Herman R. Holtslag, MD, PhD4 and Rita J. G. van den Berg-Emons, PhD1,2,5

From the 1Libra Rehabilitation & Audiology Rehabilitation Centre Leijpark, Tilburg, 2Libra Rehabilitation & Audiology Rehabilitation Centre Blixembosch, Eindhoven, 3Department of Rehabilitation, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, 4Department of Rehabilitation, University Medical Centre Utrecht and 5Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

OBJECTIVE: To assess the number and nature of complications during the acute phase following traumatic spinal cord injury and to explore the relationship between number of complications and length of hospital stay.

DESIGN: Multi-centre prospective cohort study.

Patients: A total of 54 patients with traumatic spinal cord injury, referred to 3 level 1 trauma centres in The Netherlands.

METHODS: The number and nature of complications were registered weekly from September 2009 to December 2011.

RESULTS: A total of 32 patients (59%) had 1 or more medical complications. The most common complications were pressure ulcers (17 patients, 31%) and pulmonary complications (15 patients, 28%). Patients with 3 or 4 complications had significantly (p < 0.01) longer hospital stays (58.5 [32.5] days) compared with those with 1 or 2 complications (33.1 [14.8] days) or no complications (21.5 [15.6] days).

CONCLUSION: Complications, particularly pressure ulcers and pulmonary complications, occurred frequently during the acute phase following traumatic spinal cord injury. More complications were associated with longer hospital stays. Despite the existence of protocols, more attention is needed to prevent pressure ulcers during the acute phase following traumatic spinal cord injury for patients in The Netherlands.

Key words: complication; acute-phase; traumatic spinal cord injuries.

J Rehabil Med 2014; 46: 00–00

Correspondence address: RJG van den Berg-Emons, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre Rotterdam, PO Box 2040, NL-3000 CA Rotterdam, The Netherlands. E-mail: h.j.g.vandenberg@erasmusmc.nl

Accepted Apr 15, 2014; Epub ahead of print Aug 22, 2014

Introduction

Life expectancy for patients with traumatic spinal cord injury (tSCI) has improved over the last few decades, with the mean survival rate now exceeding 30 years (1–4). Early death following tSCI, due to complications such as respiratory insufficiency or renal failure, occurs less often (2–3). During the early twentieth century, 90% of those with tSCI died within a few weeks of injury; in contrast, a 1996 study showed that only 3% of patients with tSCI died during the acute phase (4).

Despite improved acute care and greater awareness and recognition of complications, many complications still occur during this acute phase. These complications may prolong hospital stays and adversely affect the rehabilitation process (5). Only a few studies have addressed acute phase complications in tSCI. To improve acute phase care and prevent complications, more information about the number and nature of complications is needed. Recently, 2 studies have described multiple acute phase complications following tSCI in North America. These studies indicate that the most severely injured patients had the highest incidence of complications (6, 7) and that older age, absence of steroid administration, and presence of co-morbidities increased the likelihood of complications (6). Furthermore, longer hospital stays were associated with complications (6). Other previous studies of acute phase complications are outdated and most describe single complications or use retrospective designs (8–14).

The aim of this study was to assess the number and nature of complications in the acute phase following tSCI in The Netherlands. In addition, we explored the relationship between number of complications and length of hospital stay.

Methods

Participants were recruited from September 2009 to December 2011 at 3 level 1 trauma centres in The Netherlands (University Medical Centre Utrecht (UMCU), Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre (RUN MC) and St Elisabeth Hospital Tilburg (SEZ)).These 3 level 1 trauma centres provide service coverage to one-third of the Dutch population (6 million inhabitants). Patients with previous spinal cord lesions and those under 18 years of age were excluded. Because traumatic brain injury may affect respiratory and motor function, patients with severe brain injury (Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) less than 8) were excluded. Patients were classified according to the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI; formerly referred to as American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA)) for neurological level and degree of impairment (15).

In The Netherlands, patients with tSCI receive acute care management at level 1 trauma centres. In these centres, patients are treated by a neurosurgeon, orthopaedic surgeon, intensivist, neurologist, and rehabilitation physician. If necessary, other medical specialists are involved. Once medically stable, these patients are discharged to specialized SCI rehabilitation centres. Prior to transfer, patients wait at the trauma centre and begin rehabilitation. Physiotherapists and occupational therapists are involved in the treatment regarding mobilization, training of arm/hand function, and comfort in bed and/or (wheel)chair.

The 3 trauma centres participating in this study have unique protocols for acute phase tSCI management, but those protocols are largely similar. Protocols are used to optimize breathing and to prevent pressure ulcers, peptic ulcers, thrombosis and orthostatic syncope. Corticosteroids are not prescribed. Management may differ slightly for timing of surgical stabilization and decompression (“within 24 h” vs “as soon as possible”), neurogenic shock management and mobilization.

The acute phase was defined as the time from admission at a level 1 trauma centre until transfer to another facility. In addition, we distinguished complications developed whilst awaiting transfer from those developed during the period of acute treatment and stabilization. Complications were prospectively recorded by a rehabilitation physician. The focus was on complications, secondary conditions and associated conditions (for definitions see (16)); however, we refer to all of these as tSCI complications in this manuscript.

Complications were registered weekly using a fixed format: pulmonary complications (atelectasis and pneumonia), pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, gastro-duodenal ulcers, thrombotic complications (deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism), contractures, cardiovascular disorders (postural hypotension, autonomic dysreflexia and dysrhythmia), and temperature dysregulation (hypothermia and unexplained fever). Ulcers were staged according to the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel – European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP-EPUAP) Pressure Ulcer Classification System (17). Length of hospital stay was also recorded.

This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of SEZ. All patients with tSCI provided informed consent to use their medical data for evaluation in a central database.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the number and nature of complications and length of hospital stay. We tested differences in length of hospital stay between subgroups with respect to number of complications using analysis of variance with a Bonferroni post-hoc test. Because of small sample sizes, patients with 1 or 2 complications were combined into 1 category (1–2 complications); the same was done for patients with 3 or 4 complications (3–4 complications). Data analysis was performed using PASW statistics (version 21). A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patients

In total, 59 patients with acute tSCI were referred to 1 of the 3 trauma centres during the study period. Fifty-four of these patients (92%) were included in this study (UMCU, n = 19, RUN MC, n = 16 and SEZ, n = 19). One patient had severe brain injury and was excluded, and 4 were excluded for unknown reasons. Mean age at time of injury was 49 years (standard deviation (SD) 19). For 34 patients (63%), tSCI was caused by traffic accidents or leisure accidents (Table I).

|

Table I. Patient characteristics (n = 54) |

|

|

Patient characteristics |

|

|

Age, years, mean (SD) |

49 (19) |

|

Men, n (%) |

43 (80) |

|

Cause of injury, n (%) |

|

|

Leisure accident |

20 (37) |

|

Traffic accident |

14 (26) |

|

Workplace accident |

8 (15) |

|

Fall |

8 (15) |

|

Shotgun or stab wound |

2 (4) |

|

Suicide attempt |

2 (4) |

|

Neurological level, n (%) |

|

|

Cervical |

29 (54) |

|

Thoracic |

15 (28) |

|

Lumbar |

10 (19) |

|

ASIA Impairment Scale (16), n (%) |

|

|

A |

24 (44) |

|

B |

5 (9) |

|

C |

6 (11) |

|

D |

19 (35) |

|

ASIA: American Spinal Injury Association. |

|

Four of the included patients (7%) died. Two patients during the second week after trauma following pulmonary embolism (1 patient thoracic 3 ASIA D and 1 patient thoracic 4 ASIA A). Two patients died by euthanasia (1 patient cervical 4 ASIA A in week 3 and 1 patient cervical 5 ASIA A in week 4; because of the patient’s perceived low future quality of life after injury).

Complications

A total of 32 patients (59%) experienced 1 or more complications (Table II). The most frequent complication was pressure ulcer (in 31% of patients), with the sacral region being the most frequently affected. Four patients developed stage 1 ulcers, 8 developed stage 2 ulcers, 4 developed stage 3 ulcers, and 1 developed a stage 4 ulcer. The second most frequent complications were pulmonary complications (in 28% of patients). Eleven patients (20%) developed pneumonia. The mean number of complications per patient, by neurological level, were 1.7 (cervical), 1.4 (thoracic) and 0.5 (lumbar) (Table III). When grouped by severity grade according to the ISNCSCI (ASIA) Impairment Scale, the mean number of complications was 2.1 for ASIA A, 1.4 for ASIA B, 1.0 for ASIA C and 0.63 for ASIA D (Table IV).

|

Table II. Patients with complications from admission till discharge (n = 54) |

|

|

Complications |

n (%) |

|

Pulmonary complications |

15 (28) |

|

Atelectasis |

9 (17) |

|

Pneumonia |

11 (20) |

|

Pressure ulcers |

17 (32) |

|

Sacral |

13 (24) |

|

Calcaneus |

6 (11) |

|

Other |

6 (11) |

|

Urinary tract infections |

5 (9) |

|

Gastro-duodenal ulcerations |

2 (4) |

|

Thrombotic complications |

2 (4) |

|

Pulmonary embolism (fatal) |

2 (4) |

|

Elbow contractures |

3 (6) |

|

Cardiovascular disorders |

14 (26) |

|

Postural hypotension |

8 (15) |

|

Autonomic dysreflexia |

5 (9) |

|

Dysrhythmia |

6 (11) |

|

Temperature dysregulation |

8 (15) |

|

Hypothermia |

1 (2) |

|

Unexplained fever |

7 (13) |

|

Total of patients with ≥ 1 complications |

32 (59) |

|

Patients with 1 complication |

13 (24) |

|

Patients with 2 complications |

9 (17) |

|

Patients with 3 complications |

5 (9) |

|

Patients with 4 complications |

5 (9) |

|

Table III. Complications and neurological level |

|||

|

Complications |

Cervical (n = 29) n (%) |

Thoracic (n = 15) n (%) |

Lumbar (n = 10) n (%) |

|

Atelectasis |

6 (21) |

3 (20) |

|

|

Pneumonia |

6 (21) |

3 (20) |

2 (20) |

|

Pressure ulcers |

12 (41) |

4 (27) |

1 (10) |

|

Urinary tract infections |

3 (10) |

2 (20) |

|

|

Gastro-duodenal ulcerations |

1 (3) |

1 (7) |

|

|

Pulmonary embolism |

2 (13) |

||

|

Contractures |

3 (10) |

||

|

Postural hypotension |

6 (21) |

2 (13) |

|

|

Autonomic dysreflexia |

3 (10) |

2 (13) |

|

|

Dysrhythmia |

5 (17) |

1 (7) |

|

|

Hypothermia |

1 (3) |

||

|

Unexplained fever |

4 (14) |

3 (20) |

|

|

Total complications |

50 |

21 |

5 |

|

Mean per patient |

1.7 |

1.4 |

0.5 |

|

Table IV. Complications and American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale |

||||

|

Complications |

A (n = 24) n (%) |

B (n = 5) n (%) |

C (n = 6) n (%) |

D (n = 19) n (%) |

|

Atelectasis |

8 (33) |

1 (5) |

||

|

Pneumonia |

8 (33) |

1 (20) |

2 (11) |

|

|

Pressure ulcers |

7 (29) |

2 (40) |

4 (67) |

4 (21) |

|

Urinary tract infections |

2 (8) |

1 (20) |

1 (17) |

1 (5) |

|

Gastro-duodenal ulcerations |

2 (8) |

|||

|

Pulmonary embolism |

1 (4) |

1 (5) |

||

|

Contractures |

3 (13) |

|||

|

Postural hypotension |

4 (17) |

1 (20) |

1 (17) |

2 (11) |

|

Autonomic dysreflexia |

3 (13) |

1 (20) |

1 (5) |

|

|

Dysrhythmia |

6 (25) |

|||

|

Hypothermia |

1 (4) |

|||

|

Unexplained fever |

6 (25) |

1 (20) |

||

|

Total complications |

51 |

7 |

6 |

12 |

|

Mean number of complications per patient |

2.1 |

1.4 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

Length of hospital stay

Data for 8 patients were excluded from this analysis because 4 died, 1 had a missing length of hospital stay, and 3 were moved to another hospital to await rehabilitation centre transfer. Length of hospital stay at these outside hospitals was not registered.

The mean length of hospital stay was 31.3 (SD 22.2) days (range 4–125 days, n = 46). After a mean of 19.1 (SD 19.0) days (range 1–111 days), patients were medically stable for transfer. The mean waiting time between medical stability and transfer was 12.1 (SD 12.5) days (range 0–62). Sixteen patients developed complications whilst awaiting transfer; 12 of these patients developed pressure ulcers.

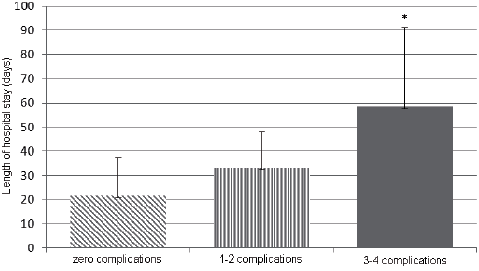

Patients with 3 or 4 complications had significantly (p < 0.01) longer mean hospital stays (58.5 (SD 32.5) days) compared with patients with 1 or 2 complications (33.1 (14.8) days) or no complications (21.5 (SD 15.6) days) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Number of complications and length of hospital stay in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injury (tSCI). *Significantly different (p < 0.01) from patients with 1 or 2 complications and from patients with 0 complications.

Discussion

These study results indicate that complications are common amongst tSCI patients during the acute phase. Nearly 60% of participants experienced 1 or more complications, with pressure ulcers and pulmonary complications being most frequent. Because complications such as postural hypotension, autonomic dysreflexia, dysrhythmia, and temperature dysregulation are associated with tSCI lesion level, we expected them to occur in our patients. However, we expected that the 3 hospitals’ use of pressure ulcer prevention protocols would have made this complication less frequent in our study. Pressure ulcers also developed during the period that patients awaited transfer.

Comparison with the 2 previous USA studies (6, 7) of multiple acute phase complications in tSCI is difficult because those studies used different complication classifications, and the study by Wilson et al. (6) only addressed cervical lesions. Grossmann et al. (7), who studied patients with similar lesion levels, reported that 58% of their participants experienced 1 or more complications (7), a rate similar to our own.

Concerning the nature of complications, Wilson et al. (6) and Grossmann et al. (7) reported, similarly to our study, frequent pulmonary complications. However, Wilson et al. (6) reported only 11 pressure ulcers in 411 patients (3%) and Grossmann et al. (7) reported a pressure ulcer rate of only 16%, compared with our rate of 31%. This discrepancy may be explained by earlier or more frequent surgical stabilization in the USA compared with The Netherlands. However, prolonged time in the operation room may also induce pressure ulcers.

Studies that have focused on single complications show wide variation in occurrence, but are generally consistent with our findings. The occurrence of atelectasis ranges from 20% to 36%, and the occurrence of pneumonia ranges from 11% to 31% (9, 12). Waring et al. reported a pulmonary embolism incidence of 5% (11). The 43% incidence of pressure ulcers reported by Nogueira et al. (14) was higher compared with our findings.

Wilson et al. (6) found that longer hospital stays were associated with complications. In our study, a larger number of complications occurred for patients with longer hospital stays. However, nearly 30% of our patients developed complications whilst awaiting transfer. Therefore, it cannot be concluded from our data that complications lead to longer hospital stays (or the converse). The mean hospital stay of 34.3 days reported by Wilson et al. (6) in their study of cervical lesions is consistent with our study.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of acute phase complications following tSCI in The Netherlands. The strengths of this study include its multi-centre design and recruitment from level 1 trauma centres covering approximately 6 million Dutch inhabitants (one-third of the Dutch population). Furthermore, 92% of eligible patients participated. In contrast with previous studies, complications were recorded prospectively. Therefore, we consider the results generalizable to the Dutch tSCI population. However, some limitations should be noted. First, because of the relatively small sample, the study is descriptive rather than hypothesis testing. Future research in a larger sample should focus on determinants of complications, among which examining both patient and treatment characteristics would be important, and risk analysis. Secondly, comparison of our results with previous studies is hampered by equivocal definitions and complication classifications. Furthermore, discrepancies may exist in the published literature regarding the definition of the “acute” phase following tSCI. We defined the acute phase as the period starting from admission in a level-1 trauma centre until transfer. In addition, we distinguished complications developed whilst awaiting transfer from complications developed before that waiting period.

In conclusion, complications, particularly pressure ulcers and pulmonary complications, occur frequently during the acute phase following tSCI. A higher number of complications are associated with longer hospital stays. Although pressure ulcer prevention protocols exist, more attention is needed to address this complication during the acute phase after tSCI in The Netherlands.

References