Makoto Nakajima, MD1, Yuichiro Inatomi, MD1, Toshiro Yonehara, MD1, Yoichiro Hashimoto, MD2, Teruyuki Hirano, MD3 and Yukio Ando, MD4

From the 1Department of Neurology, Stroke Center, Saiseikai Kumamoto Hospital, 2Department of Neurology, Kumamoto City Hospital, Kumamoto, 3Department of Neurology and Neuromuscular Disorder, Oita University Faculty of Medicine, Yufu and 4Department of Neurology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan

OBJECTIVE: To analyse the 9-year trend in oral intake ability 3 months after onset in acute stroke patients, with a view to indirect clarification of advances in acute stroke treatment and swallowing rehabilitation.

METHODS: A database of patients admitted to our hospital (Saiseikai Kumamoto Hospital, Kumamoto) with acute ischaemic stroke between 2003 and 2011 was analysed. Exclusion criteria were: patients with premorbid modified Rankin Scale score ≥ 1; those who died during hospital stay; and those whose outcomes after 3 months were not recorded. Mode of nutritional intake was investigated with a questionnaire posted to the patient 3 months after stroke onset. Patients were divided into 2 groups according to mode of nutritional intake: an oral intake group and a non-oral intake group. Whether the date or year of admission were related to the proportion of patients with oral intake, independent of other factors, was investigated using a logistic regression model.

RESULTS: Of a total of 2,913 patients, 2,677 (91.9%) were included in the oral intake group. The proportion of patients with oral intake 3 months after stroke increased significantly over the period of analysis (p = 0.034 by Cochran-Armitage test). On logistic regression analysis, the trend was significant after adjustment for age, sex, vascular risk factors, stroke subtype, and stroke severity on admission (odds ratio 1.098, 95% confidence interval 1.029–1.173; per 1 year).

CONCLUSION: The proportion of ischaemic stroke patients in the institution studied who were capable of oral intake at 3 months post-stroke increased significantly over the past decade, independent of other patient characteristics.

Key words: dysphagia; outcome; annual trends.

J Rehabil Med 2014; 46: 00–00

Correspondence address: Makoto Nakajima, Department of Neurology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kumamoto University, 1-1-1, Honjo, Chuo-ku, Kumamoto, 860-8556, Japan. E-mail: nakazima@fc.kuh.kumamoto-u.ac.jp

Accepted Sep 10, 2013; Epub ahead of print Nov 13, 2013

Introduction

Swallowing difficulty is one of the most common complications in acute stroke patients. It can cause pneumonia and malnutrition, and may result in poor functional outcome (1–3). Three-quarters of severely dysphagic stroke patients are not capable of oral intake 3 months after stroke (4), and in total, approximately 10% of stroke patients cannot eat orally after 6 months (5–7). Alternative measures for nutritional intake must be considered for these dysphagic patients. How post-stroke patients obtain nutrition in the chronic phase remains one of the important determinants of quality of life for patients and their families (2).

With marked advances in acute stroke treatment, including thrombolytic therapy, hyperacute interventional procedures, and various medical approaches, outcomes of stroke patients have improved gradually (8, 9). In addition, various attempts with regard to rehabilitation for dysphagic patients, such as bedside exercises (10), effortful swallowing training (11), electrical stimulation (11, 12), and thermal or chemical stimulation (13), also contribute, although their impact on stroke outcomes remains unclear.

We hypothesized that investigation of temporal trends of the mode of nutritional intake might indirectly demonstrate the efficacy of these various treatments and rehabilitation approaches for post-stroke patients. As far as we know, there have been no reports that have elucidated trends in the mode of nutritional intake after stroke.

The aim of this study was to investigate the 9-year trend in the proportion of patients with oral intake 3 months after onset in acute ischaemic stroke patients.

Methods

Subjects

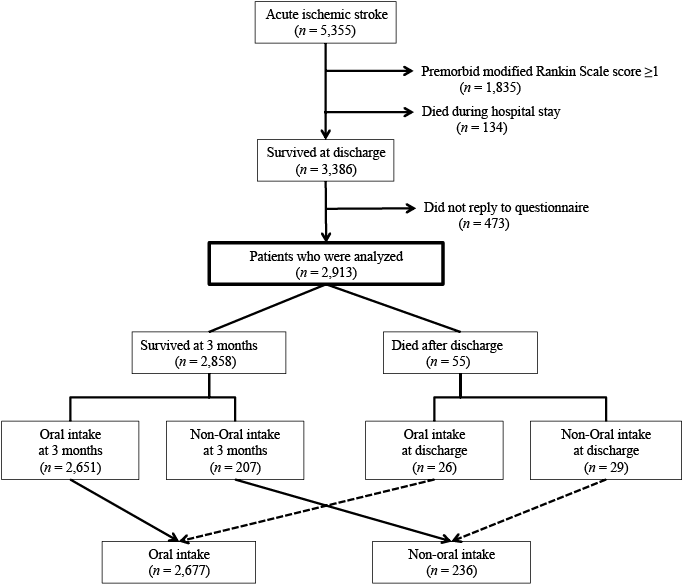

Data obtained from a prospectively registered database of consecutive acute ischaemic stroke patients admitted to our stroke centre within 7 days of onset were used (Saiseikai Kumamoto Hospital, which is located in the Kumamoto city in the south-west region of Japan. Patients are referred from the medical district with a population of over 400,000). Between April 2003 and March 2012, a total of 5,355 patients were admitted. Previous studies demonstrated that premorbid disability might strongly affect patients’ swallowing outcomes (4, 7). To validate the efficacies of stroke treatment or rehabilitation after admission more accurately, patients with a premorbid modified Rankin Scale score (14) ≥ 1 (n =1,835) were excluded. Of the remaining 3,520 patients, 134 died during the hospital stay. Three months after onset, a questionnaire was sent to the 3,386 patients who survived to be discharged. The questionnaire included the mode of nutritional intake (oral intake, nasogastric tube feeding, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), peripheral parenteral nutrition, or total parenteral nutrition). Replies were obtained from 2,913 (86.0%) patients or their family members. Therefore, the 2,913 patients were analysed in this study (Fig. 1). This article did not receive formal assessment by the institutional review board, since the study design maintained patient anonymity and did not involve any interventions.

Settings

Our hospital (Saiseikai Kumamoto Hospital) is specialized in acute care, and acute stroke patients were treated in the comprehensive stroke unit. These patients are transferred to rehabilitation hospital, other general hospital, or nursing home, unless they cannot be discharged home within 1–2 weeks. Swallowing ability is screened by trained physicians or nurses within 2 days of admission in all patients, using a standardized method in our institution (7). During the study period, 3 major changes occurred with regard to dysphagia care. First, speech/swallowing therapists started comprehensive evaluation and intervention in the acute phase in 2004. Secondly, comprehensive rehabilitation hospitals have rapidly increased in number since operations of the “liaison clinical path” was initiated in our region (Kumamoto Prefecture) in 2007. “Liaison clinical path” is a clinical schedule for patient care according to their particular diagnosis, which is intended to facilitate an integrated patient care among regional institutions including acute hospitals, rehabilitation hospitals, nursing homes, and practitioner’s offices. Thirdly, intravenous thrombolysis using alteplase was approved for use in Japan in 2005.

Clinical data recruitment

Days of admission were defined as the serial number after the beginning of the study period (1 April 2003). Each year of admission was defined as occurring from April to March. The following clinical data were collected from all patients: (i) age and sex; (ii) vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipideamia, current smoking habit); (iii) atrial fibrillation; (iv) ischaemic heart disease; (v) previous history of ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack; (vi) thrombolytic therapy in the hyperacute phase; (vii) stroke subtype based on the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification (15); (viii) National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score (16) on admission; (ix) NIHSS score on day 10 (or on discharge in patients discharged earlier); and (x) ΔNIHSS score (NIHSS score on day 10 – NIHSS score on admission).

Statistical analysis

The patients were divided into 2 groups according to the mode of nutritional intake 3 months after onset: those who could eat orally (oral intake group) and those who could not (non-oral intake group). Patients who died after discharge were divided into the each group for descriptive purposes according to their oral intake capability at discharge (see Fig. 1).

First, the relationship between the year of admission and the annual number of patients in the oral intake group was examined, as well as the relationship between the year of admission and other clinical factors. Secondly, clinical factors were compared between the oral intake group and the non-oral intake group. To investigate linear trends, the Cochran-Armitage test was used for nominal variables, and Spearman’s rank correlation test was used for continuous variables. On univariate analysis, the Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables, and the χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Finally, logistic regression analysis was performed to clarify whether there was an independent relationship between date of admission and proportion of patients achieving oral intake 3 months after stroke. The relationship between year of admission and oral intake at 3 months was also investigated. For each factor, we made a crude model and adjusted models for background characteristics that might have affected outcome.

The level of significance was p < 0.05, and Spearman’s ρ values > 0.6 were considered to indicate a clinical relevant correlation. All statistical analyses were performed using a commercially available software package (JMP 9, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Out of a total of 2,913 patients, 2,651 could take food orally 3 months after onset. Fifty-five patients died after discharge; 26 patients who were capable of oral intake at discharge were included in the oral intake group and the other 29 were included in the non-oral intake group. Therefore, the oral intake group included a total of 2,677 (91.9%) patients (Fig. 1). Increasing linear trends were observed between year of admission and hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and thrombolysis, while decreasing linear trends were observed in smoking and atrial fibrillation. The NIHSS score on admission (ρ = –0.081), the NIHSS score on day 10 (ρ = –0.067), and ΔNIHSS (ρ = 0.045) demonstrated no significant correlations with the year of admission over the study period (Table I). In terms of stroke subtype, cardioembolism showed a decreasing linear trend (p < 0.001), while other determined aetiology showed an increasing linear trend (p < 0.001).

|

Table I. Background characteristics of patients in each year of admission |

|||||||||||

|

Year of admission |

p-value |

Spearman’s ρ |

|||||||||

|

2003 n = 249 |

2004 n = 289 |

2005 n = 310 |

2006 n = 339 |

2007 n = 372 |

2008 n = 346 |

2009 n = 344 |

2010 n = 353 |

2011 n = 311 |

|||

|

Age, years, median (range) |

71 (65–77) |

72 (65–79) |

74 (67–79) |

74 (65–80) |

74 (64–80) |

73 (64–81) |

72 (63–80) |

71 (62–79) |

72 (63–79) |

0.723 |

–0.007 |

|

Sex, male, n (%) |

166 (66.7) |

192 (66.4) |

178 (57.4) |

199 (58.7) |

245 (65.9) |

227 (65.6) |

218 (63.4) |

219 (62.0) |

189 (60.8) |

0.506 |

|

|

Hypertension, n (%) |

161 (64.7) |

190 (65.7) |

209 (67.4) |

243 (71.) |

266 (71.) |

270 (78.0) |

271 (78.8) |

269 (76.2) |

229 (73.6) |

< 0.001 |

|

|

Diabetes, n (%) |

49 (19.7) |

66 (22.8) |

75 (24.2) |

99 (29.2) |

117 (31.5) |

95 (27.5) |

96 (27.9) |

103 (29.2) |

69 (22.2) |

0.115 |

|

|

Hyperlipidaemia, n (%) |

51 (20.5) |

73 (25.3) |

65 (21.0) |

85 (25.) |

91 (24.5) |

85 (24.6) |

114 (33.1) |

129 (36.5) |

118 (37.9) |

< 0.001 |

|

|

Smoking, n (%) |

69 (27.7) |

81 (28.0) |

61 (19.7) |

85 (25.1) |

90 (24.2) |

56 (16.2) |

69 (20.1) |

75 (21.3) |

57 (18.3) |

< 0.001 |

|

|

Atrial fibrillation, n (%) |

69 (27.7) |

76 (26.3) |

82 (26.5) |

60 (17.7) |

83 (22.3) |

86 (24.9) |

80 (23.3) |

74 (21.0) |

62 (19.9) |

0.021 |

|

|

Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) |

17 (6.8) |

30 (10.4) |

39 (12.6) |

37 (10.9) |

51 (13.7) |

31 (9.0) |

46 (13.4) |

30 (8.5) |

28 (9.0) |

0.949 |

|

|

Previous history of IS/TIA, n (%) |

23 (9.2) |

31 (12.1) |

29 (9.4) |

39 (11.5) |

57 (15.3) |

44 (12.7) |

43 (12.5) |

47 (13.3) |

23 (7.4) |

0.836 |

|

|

Thrombolysis, n (%) |

0 (0) |

4 (1.4) |

8 (2.6) |

22 (6.5) |

17 (4.6) |

16 (4.6) |

19 (5.5) |

17 (4.8) |

15 (4.8) |

< 0.001 |

|

|

TOAST classification, n (%) |

|||||||||||

|

Small vessel occlusion |

53 (21.3) |

97 (33.6) |

77 (24.8) |

118 (34.8) |

104 (28.0) |

106 (30.6) |

98 (28.5) |

107 (30.3) |

94 (30.2) |

0.231 |

|

|

Large artery atherosclerosis |

43 (17.3) |

40 (13.8) |

49 (15.8) |

60 (17.7) |

80 (21.5) |

62 (17.9) |

67 (19.5) |

72 (20.4) |

47 (15.1) |

0.258 |

|

|

Cardioembolism |

97 (39.0) |

94 (32.5) |

117 (37.7) |

98 (28.9) |

110 (29.6) |

118 (34.1) |

93 (27.0) |

80 (22.7) |

74 (23.8) |

< 0.001 |

|

|

Other determined aetiology |

11 (4.4) |

5 (1.7) |

4 (1.3) |

8 (2.4) |

13 (3.5) |

8 (2.3) |

14 (4.1) |

17 (4.8) |

29 (9.3) |

< 0.001 |

|

|

Undetermined aetiology |

45 (18.1) |

53 (18.3) |

63 (20.3) |

55 (16.2) |

65 (17.5) |

52 (15.0) |

72 (20.9) |

77 (21.8) |

67 (21.5) |

0.137 |

|

|

NIHSS score on admission, median (range) |

4 (2–9) |

4 (2–8) |

4 (2–8) |

4 (2–9) |

4 (2–7) |

4 (2–8) |

3 (1–6) |

3 (2–7) |

3 (2–6) |

< 0.001 |

–0.081 |

|

NIHSS score on day 10, median (range) |

2 (0–5) |

2 (1–5) |

2 (0–6) |

1 (0–5) |

1 (0–4) |

2 (0–5) |

1 (0–4) |

1 (0–5) |

1 (0–3) |

< 0.001 |

–0.067 |

|

ΔNIHSS scorea, median (range) |

–2 (–4–0) |

–1 (–3–0) |

–1 (–3–0) |

–1 (–3–0) |

–2 (–3–0) |

–1 (–3–0) |

–1 (–3–0) |

–1 (–3–0) |

–1 (–3–0) |

0.016 |

0.045 |

|

aΔNIHSS score indicates “NIHSS score on day 10 – NIHSS score on admission.” IQR: interquartile range; IS: ischaemic stroke; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; TOAST: Trial of Org Acute Stroke Treatment; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. |

|||||||||||

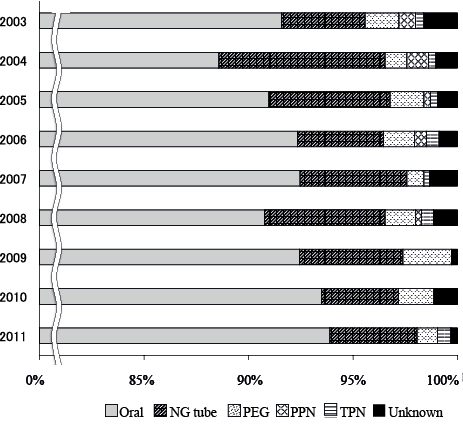

Annual trends in the mode of nutritional intake 3 months after onset are shown in Fig. 2. The proportion of patients with oral intake increased gradually with a linear trend (p = 0.034 by Cochran-Armitage test). The proportion of patients who received nasogastric tube feeding and PEG did not change significantly over the period.

Fig. 2. Annual trends in mode of nutritional intake 3 months after stroke onset. The proportion of patients achieving oral intake shows an increasing trend. Comparing the first and last 3-year periods, the average proportion of patients with oral intake increased (from 90.3% to 93.3%, p = 0.022 by Cochran-Armitage test). Unknown group includes patients who had no capability of oral intake at discharge and died subsequently. NG: naso-gastric; PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PPN: peripheral parenteral nutrition; TPN: total parenteral nutrition.

Background characteristics in the oral intake group and the non-oral intake group are shown in Table II. Younger age, male sex, hyperlipidaemia, smoking, absence of atrial fibrillation, stroke subtype, lower NIHSS score on admission, and lower NIHSS score on day 10 were significantly related to oral intake 3 months after onset. Both date of admission and year of admission revealed positive linear trends. These trends were significant after adjustment for age, sex, and other vascular risk factors (Table III).

|

Table II. Background characteristics in oral intake and non-oral intake group |

|||

|

Oral intake n = 2,677 |

Non-oral intake n = 236 |

p-value |

|

|

Age in years, median (IQR) |

72 (63–79) |

81 (75–87) |

< 0.001 |

|

Sex, male, n (%) |

1,709 (63.8) |

124 (52.5) |

< 0.001 |

|

Hypertension, n (%) |

1,938 (72.4) |

170 (72.0) |

0.906 |

|

Diabetes, n (%) |

722 (27.0) |

47 (19.9) |

0.018 |

|

Hyperlipidaemia, n (%) |

765 (28.6) |

46 (19.5) |

0.003 |

|

Smoking, n (%) |

609 (22.8) |

34 (14.4) |

0.003 |

|

Atrial fibrillation, n (%) |

544 (20.3) |

128 (54.2) |

< 0.001 |

|

Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) |

284 (10.6) |

25 (10.6) |

0.994 |

|

Previous history of IS/TIA, n (%) |

310 (11.6) |

30 (12.7) |

0.604 |

|

Thrombolysis, n (%) |

105 (3.9) |

13 (5.5) |

0.236 |

|

TOAST classification, n (%) |

< 0.001 |

||

|

Small vessel occlusion |

844 (31.5) |

10 (4.2) |

|

|

Large artery atherosclerosis |

478 (17.9) |

42 (17.8) |

|

|

Cardioembolism |

736 (27.5) |

145 (61.4) |

|

|

Other determined aetiology |

108 (4.0) |

1 (0.4) |

|

|

Undetermined aetiology |

511 (19.1) |

38 (16.1) |

|

|

NIHSS score on admission, median (IQR) |

3 (2–6) |

18 (9–26) |

< 0.001 |

|

NIHSS score on day 10, median (IQR) |

1 (0–4) |

19 (12–27) |

< 0.001 |

|

IQR: interquartile range; IS: ischaemic stroke; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; TOAST: Trial of Org Acute Stroke Treatment; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. |

|||

|

Table III. Multivariate analyses for oral intake 3 months after stroke |

||||||||

|

Crude model |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

||||||

|

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

|||

|

Date of admission (per 1 day increase) |

1.000 (1.000–1.000) |

0.035 |

1.000 (1.000–1.000) |

0.010 |

1.000 (1.000–1.000) |

0.008 |

||

|

Year of admission (per 1 year increase) |

1.060 (1.005–1.118) |

0.034 |

1.078 (1.019–1.142) |

0.009 |

1.098 (1.029–1.173) |

0.005 |

||

|

Crude model: not adjusted; Model 1: adjusted for age and sex; Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, smoking, atrial fibrillation, Trial of Org Acute Stroke Treatment subtype (small vessel disease); CI: confidence interval. |

||||||||

Discussion

The results of this study clarified annual trends of the mode of nutritional intake after stroke. As far as we know, no previous report has elucidated these trends in a large population. There was an increasing linear trend over a decade in the proportion of patients achieving oral intake 3 months after stroke onset. This trend was independent of other predictors (age, sex, vascular risk factors, and stroke severity). There are a number of possible explanations as to why patients’ outcome with respect to the mode of nutritional intake has improved over a decade.

First, decreased stroke severity might have improved swallowing function outcomes. In fact, NIHSS score both on admission and on day 10 have decreased each year (Table I). The true reason for this phenomenon remains unclear, but a possibility is that increased knowledge about stroke in the general population has resulted in patients seeking hospital care earlier (17, 18). Although the increasing trend in the proportion of patients with oral intake was independent of the NIHSS score on admission, annual changes in initial stroke severity might have affected the results. On the other hand, our initial hypothesis, that advances in acute stroke treatment have had a favourable effect on patients’ outcomes, was not confirmed. However, the NIHSS score does not necessarily reflect brain functions of particular domains related to swallowing (19–22). Therefore, it is possible that improvement in some of these brain functions during the acute or subacute phase confounded the effects.

Secondly, development of rehabilitation techniques with regard to deglutition difficulties, both in the acute and the chronic phase, might have affected the result. In our hospital, speech therapists initiated intervention for dysphagic patients in the acute phase, thus patients had more opportunities to take appropriate foods early (23, 24). Furthermore, various strategies for rehabilitation of swallowing difficulties have been attempted recently (11–13, 25). In addition, in Japan, smooth bridging from acute stroke hospitals to comprehensive rehabilitation hospitals in the past decade is also thought to affect efficient rehabilitation (26). Although data about how much patients’ oral intake ability improved during their rehabilitation could not be obtained, further ongoing analyses of the data from the “liaison clinical path” in our region may clarify this point.

Table IV shows a summary of previous cohort studies that investigated swallowing function and either short- or long-term mortality in acute stroke patients (5, 6, 19, 20, 27–35). The proportion of dysphagic patients in the present study appears to be lower than in other studies; a possible reason for this is the focus of the present study on the actual status of nutritional intake rather than on swallowing function. As a whole, there was a wide variation in patient selection, procedures for assessing swallowing function, and follow-up periods. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude that either the proportion of dysphagic patients or mortality decreased during the past 15 years. More detailed analyses could be performed by pooling the data from a number of investigations using a standard protocol.

|

Table IV. Summary of studies that investigated swallowing outcomes in acute stroke patientsa |

|||||||||

|

Year |

Study period |

Subjects |

n |

Assessment |

Follow-up |

Proportion of dysphagia, % |

Mortality rate |

Authors |

|

|

Acute phase |

Chronic phase |

||||||||

|

1987 |

NS |

ASP |

91 |

Bedside |

6 weeks |

45.1 |

20.9 (2 weeks) |

33.0 |

Gordon et al. (27) |

|

1989 |

1983–1985 |

ASP, taking medicine orally, no premorbid disability |

357 |

Bedside |

6 months |

29.0 |

0.4 |

27.5 |

Barer (28) |

|

1996 |

NS |

ASP, no decreased consciousness level |

121 |

Bedside |

6 months |

50.0 |

NS |

21.2 |

Smithard (5) |

|

1999 |

1994–1995 |

Stable ASP, no consciousness disturbance |

128 |

VFSS |

6 months |

51.0 |

11.7 |

12.5 |

Mann et al. (29) |

|

2003 |

2000 |

ASP |

149 |

Bedside |

DHS |

49.7 |

8.7 (2 weeks) |

17.4 |

Broadly et al. (19) |

|

2004 |

2001–2002 |

First-ever ASP, conscious, stable, no premorbid dysphagia |

406 |

Bedside |

3 months |

34.7 |

0.5 |

15.8 |

Paciaroni et al. (20) |

|

2005 |

NS |

ASP |

104 |

Bedside |

DHS |

52.9 |

19.2 (2 weeks) |

8.7 |

Broadly et al. (30) |

|

2008 |

NS |

Supratentorial ASP, no previous dysphagia |

67 |

FEES |

6 months |

65.1 |

10.4 |

10.4 |

Masiero et al. (6) |

|

2008 |

NS |

ASP |

50 |

Bedside |

DHS |

42.0 |

44.0 |

10.0 |

Sundar et al. (31) |

|

2008 |

1994 |

ASP, no severe consciousness disturbance, no cognitive impairment |

424 |

Bedside |

10 years |

31.6 |

NS |

4.3 (3 months) 45.8 (10 years) |

Han et al. (32) |

|

2009 |

2003–2004 |

ASP |

117 |

Bedside |

4 weeks |

42.1 |

12.8 |

6.0 |

Nakajima et al. (33) |

|

2009 |

NS |

First-ever ASP, no concomitant disease causing dysphagia |

153 |

FEES |

3 months |

52.3 |

NS |

7.8 |

Warnecke et al. (34) |

|

2012 |

2005–2006 |

First-ever ASP, no coma, no ventilation |

212 |

Bedside |

3 months |

63.2 |

NS |

18.4 |

Baroni et al. (35) |

|

2003–2005 |

ASP, premorbid mRS of 0 |

848 |

Bedside |

3 months |

22.7 |

9.7b |

7.0 |

Our study |

|

|

2006–2008 |

1,057 |

22.7 |

8.1b |

6.9 |

|||||

|

2009–2011 |

1,008 |

19.8 |

6.8b |

4.8 |

|||||

|

aStudies that included only dysphagic patients are excluded. bPatients who died during hospital stay are not included. ASP: acute stroke patients; NS: not stated; VFSS: videofluoroscopic swallowing study; FEES: fiberscopic endoscopic examination of swallowing; DHS: during hospital stay; mRS: modified Rankin Scale. |

|||||||||

This study had some limitations. First, this was a single-centre study. However, since patients’ destinations after discharge varied widely, the present results have generalizability and are of considerable importance. Secondly, the mode of the patients’ diet 3 months after stroke was evaluated by post instead of by direct assessment. Therefore, the number of patients who could eat orally might not agree with the true figure. However, investigation by post was realistic, because of the difficulty for most severely disabled patients to attend the hospital after 3 months. Thirdly, we included patients who died after discharge if they could not eat orally at discharge for descriptive purposes. These patients had higher stroke severity than other patients both on admission and on day 10 (data not shown). Therefore, most of these patients had a low chance of oral intake 3 months after onset even if they had survived.

In conclusion, this single-centre cohort study, reviewing patients between 2003 and 2011, showed that the long-term outcomes of swallowing function after acute stroke have improved slightly over time. Further observational studies in other settings are anticipated. In addition, randomized trials are required in order to validate the efficacy of a variety of dysphagia rehabilitation approaches.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References