Aleid de Rooij1, Michiel R. de Boer, PhD2,3, Marike van der Leeden, PhD1,4, Leo D. Roorda, MD, PT, PhD1, Martijn P. M. Steultjens, PhD5 and Joost Dekker, PhD1,4,6

From the 1Amsterdam Rehabilitation Research Center, Reade, 2VU University, Department of Health Sciences, Amsterdam, 3University Medical Center Groningen, Department of Health Sciences, Groningen, 4VU University Medical Centre, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine and EMGO Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 5Glasgow Caledonian University, School of Health, Glasgow, UK, 6VU University Medical Centre, Department of Psychiatry and EMGO Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the contribution of improvement in negative emotional cognitions, active cognitive coping, and control and chronicity beliefs to the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment in patients with chronic widespread pain.

DESIGN: Prospective cohort study.

Patients: A total of 120 subjects diagnosed with chronic widespread pain, who completed a multidisciplinary pain programme.

METHODS: Data from baseline, 6 months and 18 months follow-up measurements were analysed. Longitudinal relationships were analysed between changes in cognitions and outcome, using generalized estimated equations. Outcome domains included: pain, interference of pain in daily life, depression, and global perceived effect. Cognitive domains included: negative emotional cognitions, active cognitive coping and control and chronicity beliefs.

RESULTS: Improvements in negative emotional cognitions were associated with improvements in all outcome domains, in particular with improvement in interference of pain with daily life and depression (between baseline and 6 months, and 6 and 18 months). Improvements in active cognitive coping were associated with improvements in interference of pain in daily life (between baseline and 6 months). Improvements in control and chronicity beliefs were associated with improvements in pain and depression (between 6 and 18 months).

CONCLUSION: Improvement in negative emotional cognitions seems to be a key mechanism of change in multidisciplinary treatment of chronic widespread pain. Improvement in active cognitive coping and improvement in control and chronic timeline beliefs may also constitute mechanisms of change, although the evidence is less strong.

Key words: chronic widespread pain; multidisciplinary treatment; mechanisms of change.

J Rehabil Med 2014; 46: 00–00

Correspondence address: Aleid de Rooij, Amsterdam Rehabilitation Research Center, Reade, Jan van Breemenstraat 2, 1056 AB Amsterdam, The Netherlands. E-mail: a.d.rooij@reade.nl

Accepted Sep 3, 2013, Epub ahead of print Dec 5, 2013

Introduction

Chronic widespread pain (CWP) is defined as pain that is present in 2 contralateral quadrants of the body and in the axial skeleton, which must have been present for at least 3 months (1). A subcategory of patients with CWP also fulfils the criteria of fibromyalgia (FM) (1). Patients with CWP typically present complex symptoms, resulting in disability and a reduced quality of life (2). Multidisciplinary treatment programmes are recommended for patients with CWP and its associated problems (3). Core outcome domains in CWP are specified in the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) and include: (i) pain intensity; (ii) physical functioning (i.e. interference of pain with daily life); (iii) emotional functioning (i.e. depression); and (iv) study participant ratings of overall improvement (i.e. global perceived effect) (4). Evidence for positive effects of multidisciplinary treatment in FM has been reported (5). However, mechanisms of change of the multidisciplinary treatment effects are only partially understood (6, 7). Gaining a better understanding of the key mechanisms of change may help to optimize multidisciplinary treatment in CWP.

In multidisciplinary programmes for patients with CWP, pain and pain interference are regarded as the outcome of the interaction of psychological (including cognitive), physiological, and social processes (8). Changing and adjusting unhelpful or maladaptive cognitions is an important goal of multidisciplinary treatment in CWP. A number of cognitive mechanisms of change have been investigated over the years in diverse chronic pain populations. Most consistent evidence has been found for the role of catastrophizing (i.e. negative thoughts and ideas about the consequences of pain) in relation to the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment. Results from these studies show that the reduction in catastrophizing is related to a better multidisciplinary treatment outcome (9–12). Several other cognitive mechanisms of change have been suggested. These mechanisms concern belief that one is disabled (10, 13, 14), belief in control over life (15), belief that pain signals are damaging (16, 17), belief in medical cure (13), belief in medication (13), belief in pain control (9–11, 13, 14), acceptance (12), belief of serious consequences of pain, sense of coherence, emotional representations of pain (18), negative thinking (11), pain vigilance (18) use of cognitive coping styles; coping self-statements (14), praying and hoping (16), and ignorance of pain (10).

The above-mentioned results show that the spectrum of potential cognitive mechanisms of change is very broad. It can be argued that these cognitive mechanisms show considerable overlap (17, 19). In an empirical study, we have shown that there is indeed overlap between cognitive concepts frequently used in the explanation of CWP (19). That cross-sectional study showed that these concepts could be clustered into 3 principal domains: negative emotional cognitions; active cognitive coping; and control and chronicity beliefs. Negative emotional cognitions are characterized by negative and emotional thoughts that hinder adjustment to chronic pain. Active cognitive coping is characterized by the cognitive efforts of a person to manage or undo the negative influence of pain. Finally, control and chronicity beliefs are characterized by thoughts and expectations about the controllability and chronicity of the illness.

A longitudinal design is the next logical step in evaluating whether improvement in these cognitive domains is associated with the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment. If improvement in negative emotional cognitions is the primary mechanism of change, one would expect improvement in this domain to be associated with the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment. Similarly, if improvement in active cognitive coping or improvement in control and chronicity beliefs constitute mechanisms of change, one would expect improvement in these domains to be associated with the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment in CWP. A longitudinal study on these associations has the potential to show in which cognitive domain(s) mechanisms of change are primarily located, thereby narrowing down the number of hypothesized cognitive mechanisms of change. Results from this study may direct the optimization of treatment programmes for patients with CWP. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the contribution of improvement in negative emotional cognitions, active cognitive coping, and control and chronicity beliefs to the outcome (i.e. pain, interference of pain, depression and global perceived effect) of multidisciplinary treatment of patients with CWP.

Patients and Methods

Design

Data were obtained in a longitudinal observational study. Baseline measurements were made before the start of a multidisciplinary treatment programme (T0). The second and third assessments were performed 6 (T1) and 18 months (T2) after baseline, respectively. The estimated number of patients to be included was 120, which would enable the establishment of a statistically significant correlation of r > 0.20 (20) between the dependent and independent variables. To allow for drop-out of patients the inclusion number was increased to 138. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Slotervaart Hospital and the Reade Institute in Amsterdam. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Patients and procedure

Patients with chronic pain were referred by rheumatologists and general practitioners to the rehabilitation physician to assess their problems and to evaluate eligibility for participation in the multidisciplinary pain programme. Potential participants for the study were screened for their eligibility by the rehabilitation physicians of the pain management team. Inclusion criteria were: (i) age between 18 and 75 years (ii) diagnosis of CWP according to the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) (1); (iii) eligible for multidisciplinary treatment according to the criteria of the Dutch Consensus Report of Pain Rehabilitation (21), as assessed by both a rehabilitation physician and a psychologist. These criteria require patients to experience restrictions in daily living (e.g. sports or work) and/or psychosocial functioning. Exclusion criteria were: (i) pain resulting from known specific pathology (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis or Ankylosing spondylitis); (ii) not eligible for multidisciplinary pain treatment because of a somatic disorder, social problem and/or psychiatric disorder (e.g. major depression), or because the patient was currently involved in a legal procedure of conflicting interest, was currently receiving pain treatment elsewhere, or was not motivated for behavioural change; (iii) insufficient control of the Dutch language to complete questionnaires; and (iv) refusal to provide informed consent.

A consecutive series of patients was included in the study. Recruitment took 14 months. Baseline measurements were integrated into the existing intake at our centre. Participants were contacted by telephone to inform them that the follow-up questionnaires had been sent by post. Patients were asked to return the questionnaires by post within 2 weeks. After 2 weeks patients were phoned by the study researcher and a reminder was sent if the questionnaires were not returned in time.

Intervention

All study participants entered the multidisciplinary treatment programme, the main goal of which was to teach patients to cope with pain and to reduce the interference of pain in their daily lives. The programme included education about neuro-physiology and medication management, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), the acquisition of pain management skills (e.g. goal setting, structuring of daily activities, pacing strategies, and ergonomics), physical training (e.g. exercise), relaxation training, and assertiveness training. The components of the multidisciplinary treatment were in line with the core elements of multidisciplinary treatment in CWP (5). Treatment was tailored to the patient’s personal goals and was performed in groups and on an individual basis. In addition, patients were asked to make a personalized plan, taking into account their individual needs and requirements. Group treatment consisted of 7 consecutive weeks of treatment, 7 h a week, and was divided into 2 sessions a week of multidisciplinary treatment. Individual treatment was offered during a period of 4–6 months with a variable frequency per patient. There was an opportunity for 2 post-treatment appointments to evaluate personal goals. The multidisciplinary team involved rehabilitation physicians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychologists, and social workers. The multidisciplinary team discussed the treatment progress of patients during regular team meetings.

Outcome measures

Four outcome domains were defined, in accordance with the recommendations of the IMMPACT (4), i.e. pain, physical functioning, emotional functioning, and global perceived effect. Pain was assessed with the Numerical Rating Scale Pain (NRS) (22). Physical functioning was assessed with the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI) – subscale interference (23). Emotional functioning was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI–II) (24–26). Global perceived effect (GPE) due to treatment was assessed with a 7-point Likert scale. The scale was dichotomized into 0 = no change/worse and 1 = improved. For additional descriptive information and psychometric properties of the measurements, see Appendix SI1.

Cognition measures

The cognitive variables described below are arranged according to the 3 cognitive domains found in our previous study (19), i.e. negative emotional cognitions, active cognitive coping, and control and chronicity beliefs.

Negative emotional cognitions. Negative emotional cognitions were assessed with 3 questionnaires. Three subscales of the Revised Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (IPQ-R) were used to assess the illness beliefs; (1) consequences; (2) coherence; (3) emotional representations (27–29). The Dutch General Self-efficacy Scale (DGSS) was used to measure general self-efficacy beliefs (30–32). The Dutch adaptation of the Coping Strategy Questionnaire (CSQ) was used to assess the cognitive coping style “catastrophizing” (33). For additional descriptive information and psychometric properties of the measurements, see Appendix SI1.

Active cognitive coping. Four subscales of the Dutch adaptation of the CSQ, were used to assess the active cognitive coping styles; (1) denial of pain sensations; (2) positive self-statements; (3) reinterpreting pain sensations; (4) diverting attention away from pain sensations (33). For additional descriptive information and psychometric properties of the measurements, see Appendix SI1.

Control and chronicity beliefs. Control and chronicity beliefs were assessed with the use of 2 questionnaires. The Revised Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (IPQ-R) was used to measure the illness beliefs; (1) timeline; (2) timeline cyclical; (3) personal control, (4) treatment control (27, 28). The Dutch adaptation of the CSQ was used to assess the cognitive coping style “perceived control over pain” (33). For additional descriptive information and psychometric properties of the measurements, see Appendix SI1.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe the main characteristics of the study population. Independent variables included: negative emotional cognitions, active cognitive coping, and control and chronicity beliefs. Dependent variables included: pain, interference of pain in daily life, depression, and GPE. Change scores were calculated for the independent variables and continuous dependent variables by subtracting the T0 scores from the T1 scores, and the T1 scores from the T2 scores. The changes in cognitions and outcome measurements over time were investigated using generalized estimating equations (GEE) statistics. GEE is a longitudinal regression technique that enables correction for dependency of observations within individuals over time by choosing a “working” correlation structure (34). For the analyses of the changes in cognitions and outcome measurements over time an exchangeable correlation matrix was found to be most appropriate. The associations between changes in cognitions and changes in outcome measurements (i.e. pain, interference of pain and depression) from baseline to T1 and from T1 to T2 were analysed according a Model of Change (see Fig. 1), using GEE statistics. For the outcome measure GPE the change in cognitions between T0–T1 and T1–T2 was related to the outcome of GPE at T1 and T2, respectively. An independent correlation structure was most appropriate for the analysis of the Model of Change of the continuous outcome variables, and an exchangeable correlation structure was deemed most appropriate for analyses of the dichotomous outcome variable (34). These models concerning the associations between changes in cognitions and changes in the outcomes were all adjusted for age and gender. All analyses were carried out using SPSS 18.0, and an alpha of 0.05 was used in all statistical tests.

Results

Study population

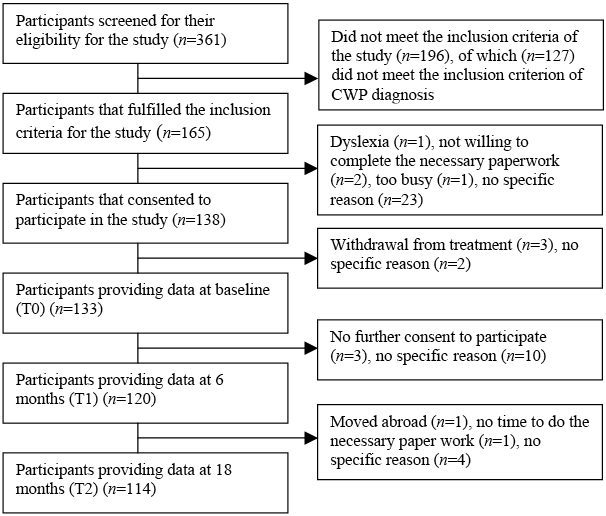

Patient flow through the study is illustrated in Fig. 2. Of the 361 patients referred to and screened by the rehabilitation physician, 165 fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this study and a final 138 agreed to participate. Of these 138 participants, 133 provided data at T0, 120 provided data at T1, and 114 provided data at T2. Patient characteristics are shown in Table I.

Fig. 2. Study flowchart.

|

Table I. Patients characteristics and change in outcome and cognitive variables |

||||||

|

T0 (n = 120) |

T1 (n = 120) |

T2 (n = 114) |

p-value T0–T1 |

p-value T1–T2 |

p-value T0–T2 |

|

|

Patient characteristics |

||||||

|

Female, % |

95.0 |

|||||

|

Age, years, mean (SD) |

45.04 (10.30) |

|||||

|

Partnership, % Yes No |

50.8 49.2 |

|||||

|

Ethnicity, % Native Western non-native Non-Western non-native |

70.8 12.5 16.7 |

|||||

|

Education, % Primary Secondary High |

17.6 49.6 32.8 |

|||||

|

Pain duration in months, median (IQR) |

84 (39–168) |

|||||

|

Depression, BDI–II, mean (SD) |

20.79 (8.86) |

17.61 (9.53) |

16.62 (9.97) |

≤ 0.001*** |

0.05* |

≤ 0.001*** |

|

Interference, MPI, mean (SD) |

4.07 (1.06) |

3.87 (1.13) |

3,79 (1.29) |

0.01** |

0.10 |

0.002** |

|

Pain (NRS), mean (SD) |

6.08 (2.08) |

6.08 (1.89) |

5.81 (2.33) |

0.96 |

0.21 |

0.20 |

|

Global perceived effect, % No change/worse Improved |

51.7 48.3 |

63.2 36.8 |

||||

|

Negative emotional cognitions, mean (SD) |

||||||

|

Consequence (IPQ) |

20.93 (4.36) |

20.95 (4.28) |

20.59 (4.56) |

0.96 |

0.10 |

0.16 |

|

Emotional representation (IPQ) |

19.15 (4.66) |

18.02 (4.72) |

17.62 (5.33) |

0.01** |

0.23 |

≤ 0.001*** |

|

Coherence (IPQ) |

14.99 (4.81) |

13.63 (4.42) |

13.50 (4.76) |

≤ 0.001*** |

0.54 |

≤ 0.001*** |

|

Catastrophizing (CSQ) |

23.85 (11.04) |

19.80 (12.12) |

18.25 (12.19) |

≤ 0.001*** |

0.10 |

≤ 0.001*** |

|

General self-efficacy (DGSS) |

2.93 (0.61) |

2.99 (0.63) |

3.03 (0.58) |

0.19 |

0.15 |

0.01** |

|

Active cognitive coping |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reinterpreting pain (CSQ), median (IQR) |

10.00 (5.00–20.00) |

12.00 (6.00–19.00) |

9.50 (4.00–19.30) |

0.52 |

0.58 |

0.92 |

|

Diverting attention (CSQ), mean (SD) |

21.16 (12.45) |

20.10 (11.42) |

19.29 (12.10) |

0.27 |

0.61 |

0.13 |

|

Positive self statements (CSQ), mean (SD) |

36.11 (11.44) |

35.06 (11.41) |

34.76 (12.01) |

0.27 |

0.92 |

0.23 |

|

Denial of pain (CSQ), mean (SD) |

28.64 (13.17) |

27.50 (11.91) |

26.76 (12.84) |

0.36 |

0.53 |

0.14 |

|

Control and chronicity beliefs |

||||||

|

Perceived control (CSQ), mean (SD) |

8.20 (4.53) |

9.37 (4.63) |

8.73 (4.75) |

0.01** |

0.23 |

0.27 |

|

Personal control (IPQ), mean (SD) |

18.56 (4.31) |

19.19 (4.69) |

18.43 (4.69) |

0.10 |

0.05* |

0.76 |

|

Treatment control (IPQ), mean (SD) |

16.17 (2.93) |

14.63 (3.41) |

13.97 (3.83) |

≤ 0.001*** |

0.05* |

≤ 0.001*** |

|

Timeline cyclical (IPQ), mean (SD) |

15.29 (3.21) |

14.92 (3.33) |

14.70 (3.76) |

0.11 |

0.42 |

0.04* |

|

Timeline (IPQ), mean (SD) |

23.00 (12.00–30.00) |

24.00 (12.00–30.00) |

25.00 (9.00–30.00) |

0.002** |

0.99 |

0.01** |

|

p-values are analysed with GEE statistics, to correct for dependency of repeated variables. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. T0: baseline; T1: follow-up at 6 months; T2: follow-up at 18 months; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; BDI–II: Beck Depression Inventory; CSQ: Coping Scale Questionnaire; DGSS: Dutch General Self efficacy Scale: IPQ: Illness Perception Questionnaire; MPI: Multidimensional Pain Inventory; NRS: Numerical Rating Scale. |

||||||

Change in outcome and cognitive variables

The mean changes in outcome and cognitions are presented in Table I. Significant improvements in interference of pain and depression were found over 6 and 18 months. With respect to the change in cognitions, we found significant improvements in negative emotional cognitions over time. Emotional representations, illness coherence and catastrophizing improved over 6 and 18 months, and self-efficacy improved over 18 months. In addition, significant improvements were found for control and chronicity beliefs. Treatment control and timeline beliefs improved over 6 and 18 months, perceived control improved over the first 6 months only and beliefs in a cyclical timeline improved over 18 months.

Relationship between change in negative emotional cognitions and outcome variables

The results of the analyses of the association between change in negative emotional cognitions and the outcome variables are shown in Table II. Improvements in negative emotional cognitions were associated with improvements in all outcome domains, in particular with improvement in interference of pain in daily life and depression. Improvement in catastrophizing between T0 and T1 was significantly associated with improvement in interference of pain in daily life over this time interval. Improvement in belief in consequences and emotional representations between T1 and T2 were significantly associated with improvement in interference of pain in daily life over this time interval. Improvement in belief in consequences, emotional representations, catastrophizing, and self-efficacy between T0–T1 and T1–T2 were significantly associated with improvement in depression over the same time intervals. ’In addition, improvement in emotional representations between T1 and T2 was significantly associated with improvement in pain over this time interval. Finally, improvement in catastrophizing between T0 and T1 was significantly associated with better global perceived effect at T1; and improvement in emotional representations over T1–T2 was significantly associated with better global perceived effect at T2.

|

Table II. Results of the longitudinal analyses of the relationship between change in cognitions and multidisciplinary treatment outcome |

||||||||

|

Pain T0–T1 β (95% CI) |

Pain T1–T2 β (95% CI) |

Interference of pain T0–T1 β (95% CI) |

Interference of pain T1–T2 β (95% CI) |

Depression T0–T1 β (95% CI) |

Depression T1–T2 β (95% CI) |

GPE T1 Odds ratio (95% CI) |

GPE T2 Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

|

Negative emotional cognitions |

||||||||

|

More consequences (IPQ) |

0.03 (–0.06 to 0.11) |

0.07 (–0.03 to 0.17) |

0.04 (–0.02 to 0.10) |

0.06 (0.02 to 0.10)** |

0.56 (0.17 to 0.95)** |

0.50 (0.09 to 0.90) * |

0.91 (0.81 to 1.01) |

0.95 (0.84 to 1.08) |

|

More emotional representations (IPQ) |

0.05 (–0.01 to 0.12) |

0.15 (0.05 to 0.25)** |

0.02 (–0.03 to 0.07) |

0.05 (0.02 to 0.08)*** |

0.53 (0.11 to 0.96)** |

0.47 (0.21 to 0.74)*** |

0.99 (0.90 to 1.08) |

0.87 (0.78 to 0.97)** |

|

Less illness coherence (IPQ) |

–0.06 (–0.15 to 0.03) |

–0.04 (–0.11 to 0.03) |

0.01 (–0.04 to 0.05) |

0.01 (–0.02 to 0.05) |

0.26 (–0.02 to 0.540) |

0.30 (–0.08 to 0.68) |

1.01 (0.93 to 1.10) |

1.05 (0.96 to 1.16) |

|

More self efficacy (DGSS) |

0.48 (–0.19 to 1.16) |

0.25 (–0.72 to 1.23) |

–0.19 (–0.51 to 0.13) |

–0.01 (–0.34 to 0.33) |

–5.68 (–8.71 to –2.65)*** |

–3.82 (–7.25 to –0.38)* |

0.77 (0.37 to 1.61) |

0.69 (0.27 to 1.75) |

|

More catastrophizing (CSQ) |

–0.01 (–0.05 to 0.03) |

0.01 (–0.04 to 0.05) |

0.02 (0.001 to 0.03) * |

0.01 (–0.002 to 0.02) |

0.33 (0.18 to 0.47) *** |

0.37 (0.23 to 0.50) *** |

0.96 (0.93 to 1.00)* |

0.98 (0.93 to 1.02) |

|

Active cognitive coping |

||||||||

|

More reinterpretation of pain (CSQ) |

–0.02 (–0.05 to 0.01) |

0.02 (–0.01 to 0.04) |

–0.02 (–0.03 to –0.01)** |

0.001 (–0.01 to 0.02) |

–0.05 (–0.18 to 0.08) |

0.02 (–0.15 to 0.19) |

1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) |

0.96 (0.92 to 1.00) |

|

More positive self statements (CSQ) |

–0.02 (–0.05 to 0.01) |

0.003 (–0.04 to 0.04) |

–0.02 (–0.03 to –0.01)** |

0.003 (–0.01 to 0.02) |

–0.14 (–0.30 to 0.01) |

0.02 (–0.12 to 0.16) |

1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) |

1.00 (0.96 to 1.04) |

|

More denial of pain (CSQ) |

–0.01 (–0.04 to 0.02) |

–0.01 (–0.04 to 0.01) |

–0.01 (–0.02 to 0.002) |

0.003 (–0.01 to 0.01) |

–0.04 (–0.17 to 0.09) |

0.06 (–0.04 to 0.16) |

1.00 (0.97 to 1.02) |

0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) |

|

More diverting attention (SCQ) |

–0.02 (–0.05 to 0.01) |

0.01 (–0.03 to 0.04) |

–0.01 (–0.02 to 0.01) |

0.01 (–0.01 to 0.02) |

–0.04 (–0.16 to 0.07) |

0.10 (–0.04 to 0.23) |

1.00 (0.97 to 1.03) |

0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) |

|

Control and chronicity beliefs |

||||||||

|

More perceived pain control (CSQ) |

–0.05 (–0.12 to 0.03) |

–0.09 (–0.17 to –0.02)** |

–0.01 (–0.04 to 0.03) |

0.001 (–0.03 to 0.04) |

–0.03 (–0.36 to 0.31) |

–0.03 (–0.26 to 0.20) |

0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) |

1.01 (0.94 to 1.10) |

|

More personal control (IPQ) |

0.003 (–0.09 to 0.09) |

–0.04 (–0.11 to 0.04) |

–0.03 (–0.07 to 0.004) |

–0.01 (–0.04 to 0.02) |

–0.13 (–0.56 to 0.29) |

–0.37 (–0.64 to –0.11)** |

1.03 (0.95 to 1.12) |

1.01 (0.93 to 1.09) |

|

More treatment control (IPQ) |

–0.04 (–0.13 to 0.05) |

–0.11 (–0.21 to –0.02)* |

–0.004 (–0.05 to 0.04) |

–0.01 (–0.05 to 0.03) |

–0.34 (–0.75 to 0.07) |

–0.18 (–0.48 to 0.13) |

1.07 (0.97 to 1.18) |

1.02 (0.92 to 1.12) |

|

Stronger timeline (IPQ) |

0.05 (–0.04 to 0.14) |

0.11 (0.03 to 0.18)** |

–0.01 (–0.04 to 0.03) |

0.02 (–0.01 to 0.05) |

0.06 (–0.34 to 0.47) |

0.32 (0.04 to 0.60)* |

0.95 (0.87 to 1.04) |

0.94 (0.85 to 1.05) |

|

Stronger timeline cyclical (IPQ) |

0.08 (–0.06 to 0.22) |

0.12 (0.02 to 0.23)* |

0.04 (–0.03 to 0.10) |

0.03 (–0.01 to 0.06) |

–0.30 (–0.84 to 0.25) |

0.33 (–0.09 to 0.75) |

1.08 (0.94 to 1.23) |

0.94 (0.84 to 1.06) |

|

β and odds ratio are adjusted for age and gender. Negative β indicates: associations of cognitions with better treatment outcome. Positive β indicates: associations of cognitions with worse treatment outcome. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. T0–T1: change in outcome variables between baseline and 6 months; T1–T2: change in outcome variables between 6 and 18 months; β: regression coefficient; CI: confidence interval; GPE: Global Perceived Effect; CSQ: Coping Scale Questionnaire; DGSS: Dutch General Self-efficacy Scale; IPQ: Illness Perception Questionnaire. |

||||||||

Relationship between change in active cognitive coping and the outcomes

The results of the analyses of the association between change in active cognitive coping and the outcome variables are also represented in Table II. Overall, few associations were found, except that improvement in the cognitive coping styles “reinterpreting pain” and “positive self statements” between T0 and T1 were significantly associated with improvement in interference of pain in daily life over the same time interval.

Relationship between change in control and chronicity beliefs and the outcomes

Table II shows the results of the analyses of the association between change in control and chronicity beliefs and the outcome variables. Relationships were most consistently found with changes in pain between T1 and T2. Improvement in perceived pain control, treatment control, timeline and cyclical timeline beliefs between T1 and T2 were significantly associated with improvement in pain over the same time interval. In addition, improvement in personal control and timeline beliefs between T1 and T2 were significantly associated with improvement in depression over this time interval.

Discussion

A wide variety of cognitive mechanisms of change of multidisciplinary treatment in CWP has been suggested. We have clustered cognitive mechanisms into 3 principal domains, i.e. negative emotional cognitions, active cognitive coping, and control and chronicity beliefs. Changes in these cognitive domains were related to the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment defined by the IMMPACT core set in CWP. Our results show that improvements in negative emotional cognitions were more consistently associated with a beneficial outcome of multidisciplinary treatment. Improving negative emotional cognitions may be a key mechanism of change in multidisciplinary treatment. Other, less central, mechanisms of change may include improving active cognitive coping and improving control and chronicity beliefs.

Our findings show that improvements in negative emotional cognitions were associated with improvements in all outcome domains, in particular with improvement in interference of pain in daily life and depression in the short-term as well in the long-term. The separate cognitive constructs within the domain of negative emotional cognitions related to the outcome included: beliefs in serious consequences of the illness, emotional representations, self-efficacy, and catastrophizing. According to cognitive behavioural models (35–37) and previous studies (9–12, 18) these cognitions are assumed to play an important role in the adjustment to chronic pain. In a cross-sectional study, we have previously demonstrated that these cognitions overlap and that they can be clustered into the domain negative emotional cognitions (19). The present longitudinal study shows that improvement in cognitions in this domain is most consistently related to the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment. This suggests that improvement in negative emotional cognitions is a key mechanism of change in multidisciplinary treatment of patients with CWP.

It has been assumed that improving active cognitive coping is an important mechanism of change to improve the outcome of treatment (38, 39). Our results show that only improvements in reinterpreting pain and use of positive self-statements were associated with improvement in interference of pain. This suggests a modest role for active cognitive coping cognitions with regard to the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment. Our findings suggest that other cognitive processes might contribute more to the adjustment to chronic pain than improvement in active cognitive coping; improvements in negative emotional cognitions and control and chronicity beliefs were more consistently associated with a beneficial treatment effect. These findings support the conclusion of Jensen et al. (10), that coping strategies may have a limited impact on outcomes. Active cognitive coping might play a less important role than was hypothesized previously. It should be noted that in our study we focused only on the assessment of cognitive coping. Behavioural coping (e.g. resting or being active) were not included. Alternatively, it might be possible that (cognitive) pain coping efforts, which tend to be dynamic, are insufficiently captured by the questionnaire used in our study (i.e. a Dutch adaptation of the CSQ (40).

Improvement in control and chronicity beliefs was associated with improvement in pain and depression on the long-term. Stronger beliefs that the “illness can be cured or controlled” and less belief in “chronicity of the illness” were associated with improved outcome of multidisciplinary treatment. In other studies, the role of improving control beliefs has been highlighted (9, 11, 13, 14). Our study shows that improving control and chronicity beliefs may, to some extent, be a mechanism of change.

The results of this study show that improvements in cognitions were positively associated with the outcome of treatment. Although the improvements in cognitions were small on a group level, the individual variation in improvements was related to the effect of treatment. For multidisciplinary treatment this suggests that it is important to determine which cognitions play a part in each patient with CWP. Targeting these specific cognitive mechanisms in individual patients may help to improve further the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment.

Significant relationships between improvements in cognitions and outcome were found between 0 and 6 months, and between 6 and 18 months of follow-up. Although most of the treatment took place during the first 6 months, improvement in negative emotional cognitions and control and chronicity beliefs also occurred at a later stage. These improvements were positively related to the outcome of treatment. These findings suggest that patients are in a long-term process of change. Little research has been carried out into changes in cognitions in the long-term and their relationship with treatment outcome. One previous study found evidence for the relationship between a worsening in catastrophizing and control beliefs after 6 months and a negative treatment outcome in the long-term (10). Further studies will be needed to clarify: (i) the impact of changes in cognitions in the long-term on the effect of treatment; and (ii) how to sustain improvements in cognitions in the long-term.

There are several limitations that warrant attention. Firstly, the study design does not allow conclusions to be drawn regarding causal relationships. It is possible that improvement in cognitions occurred because of reductions in emotional functioning or physical function, rather than the other way around, as hypothesized in the present study. Secondly, evaluating predictors of change in uncontrolled studies does not enable us to distinguish between predictors of natural course of a disorder and predictors of successful treatment. Randomized controlled trials with a non-treated control group are needed to distinguish between predictors of the natural course of CWP and predictors of successful treatment of CWP. However, in clinical practice treatment effect is always a sum of the effect of natural course and the effect of treatment. Thirdly, measurement error may have lead to an underestimation of true relationships. Fourthly, the multiple testing may have caused us to find some false positive associations. However, changing the alpha level to 0.01 to reduce the risk of type 1 errors does not alter our conclusions. Finally, the intensity and length of the intervention was not standardized in our study. In theory, it might be possible that the mechanisms of change differ between interventions with different intensity and length. Additional studies are necessary to develop a greater understanding of the influence of treatment intensity on mechanisms of change and the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment in patients with CWP.

A wide range of cognitive mechanisms has been proposed over the years to explain the adjustment to and persistence of chronic pain. Current cognitive mechanisms (with accompanying measurements) in chronic pain have become rather diverse and complex. The results of this study contribute to a better understanding of the key cognitive mechanisms of change in the multidisciplinary treatment and may therefore provide a clearer direction for the optimization of multidisciplinary treatment programmes for patients with CWP. In particular, our results highlight the relationships between improvement in negative emotional cognitions and the outcome of multidisciplinary treatment. This means that if negative emotional cognitions are present in patients with chronic pain these cognitions are a worthwhile treatment target.

In conclusion, improvement in negative emotional cognitions seems to be a key mechanism of change of multidisciplinary treatment in CWP. Improvement in active cognitive coping and in control and chronic timeline beliefs may also constitute mechanisms of change, although the evidence is less strong.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr D. G. de Rooij for advice and critical reading of the manuscript.

1http://www.medicaljournals.se/jrm/content/?doi=10.2340/16501977-1252

References