OBJECTIVE: To describe the proportion of people with spinal cord injury who returned to work 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, and to investigate whether return to work is related to wheelchair capacity at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation.

DESIGN: Multi-centre prospective cohort study.

SUBJECTS: A total of 103 participants with acute spinal cord injury at 8 Dutch rehabilitation centres, specialized in the rehabilitation of spinal cord injury. All participants were in paid employment before injury.

METHODS: Main outcome measure was return to work for at least 1 h per week. The independent variables of wheelchair capacity were peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak), peak aerobic power output (POpeak), and wheelchair skill scores (ability, performance time, and physical strain). Possible confounders were age, gender, lesion level and lesion completeness, and educational level.

RESULTS: The proportion of participants who returned to work was 44.7%. After correction for the confounders, POpeak (p = 0.028), ability score (p = 0.022), performance time (p = 0.019) and physical strain score (p = 0.038) were significantly associated with return to work. VO2peak was not significantly associated with return to work.

CONCLUSION: More than 40% of the participants were able to return to paid work within 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Return to work was related to wheelchair capacity at discharge. It is recommended to train wheelchair capacity during rehabilitation in the context of return to work, since the association with return to work is another benefit of the training of wheelchair capacity in addition to the improvement of mobility and functional independency.

Key words: employment; spinal cord injuries; rehabilitation; wheelchairs; physical fitness.

J Rehabil Med 2012; 00: 00–00

Guarantor’s address: J. M. van Velzen, Heliomare Research and Development, PO Box 78, 1940 AB Beverwijk, The Netherlands. E-mail: j.van.velzen@heliomare.nl

Submitted December 2, 2010; accepted August 30, 2011

Introduction

Return to work (RTW) is known to influence quality-of-life of people with spinal cord injury (SCI) (1–4). People with SCI who are employed report a better sense of wellbeing, better health status, less health service usage and more social contacts compared with people with SCI who are not working (1–4). RTW after SCI is therefore important. However, RTW after SCI is not always achieved. Rate of RTW may vary between 21% and 67%, due to study design, definition of employment and differences in geographical location (5, 6). In a recent review it was concluded that at least 12 months after SCI 40% of the people of working age returned to work (6). The rate of RTW appears to increase with time post-injury (5, 6). According to a study by Krause (7) mean time between injury and first post-injury job is 4.8 years, while mean time between injury and first full-time job is 6.3 years.

Many different factors are known to influence RTW; for example, level and completeness of the lesion (7–10) and age (7, 9, 11). However, to be able to help people to return to work, it is useful to focus on factors that can be influenced during the (inpatient) rehabilitation process. In an earlier paper, we investigated whether successful RTW one year after discharge was related to wheelchair capacity (WC) at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation (12). Wheelchair capacity was determined by the ability to perform wheelchair skills and, related to that, physical capacity (13). The study showed that 33% of the people who were working before the SCI returned to work one year after discharge, and that RTW was associated with 3 out of 5 WC variables (peak power output, ability score and performance time) measured at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation (12). Peak oxygen uptake and physical strain score were not associated with RTW. However, measuring RTW one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation is relatively early, taking into consideration the known relationship between time since injury and RTW (5, 6). It is possible that people were still receiving outpatient rehabilitation one year after inpatient rehabilitation. Moreover, it can be expected that people needed time to adjust to their new life at home. To obtain data on RTW at a later stage post-SCI and to confirm, or reject, our earlier findings, we investigated RTW and the influence of WC in the same cohort at 5 years after discharge. The aims of the current study were: (i) to describe the proportion of people with SCI who have returned to work and describe their working situation 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, and (ii) to investigate whether WC at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation is related to successful RTW at 5 years after discharge.

METHODS

Participants

The study was part of the Dutch Research Project “physical strain, work capacity, and mechanisms of restoration of mobility in the rehabilitation of persons with a spinal cord injury” (14). All participants who were admitted to inpatient rehabilitation in 1 of the 8 Dutch rehabilitation centres specialized in the rehabilitation of SCI between August 2000 and July 2003 and who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were asked to participate by their medical doctor. Inclusion criteria were: (i) having an acute SCI, (ii) age between 18 and 65 years, (iii) remaining or expected to remain wheelchair dependent, (iv) sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language to understand the goal of the study and the testing methods, and (v) no progressive disease or psychiatric problem. Participants were excluded for the physically demanding tests if they had cardiovascular contraindications or musculoskeletal complaints. After being informed about the study, participants completed a written informed consent. All patients participated on a voluntary basis.

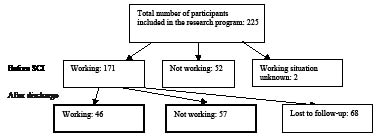

A total of 225 people with SCI participated in the Dutch Research Project (Fig. 1). Of these participants, 171 were working 1 h or more before the occurrence of SCI. As in the former study (12), it was decided to include only those people who were working before SCI because most people who were not working were either retired or taking care of the household and, therefore, not expected to work after SCI. Of the 171 participants, 68 dropped out of the study due to several reasons, such as having moved to another country (n = 1), having passed away (n = 21), not being able to be traced (n = 10), not being willing to participate any further (n = 21), not being able to be measured before the RTW analysis (n = 11), no longer fulfilling the inclusion criteria (n = 3), or changing day and night rhythm resulting in an inability to be measured (n = 1) (15). There were no significant differences in WC, and personal and lesion characteristics between the people who did or did not drop out of the study. The analyses in the current study were, therefore, based on the data of the 103 participants who were working before the occurrence of SCI and of whom it was known whether they were working 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of the participants before spinal cory injury (SCI) and 5 years after discharge of inpatient rehabilitation.

Procedure

The medical ethics committee of the Institute for Rehabilitation Research/Stichting Revalidatie Limburg, Hoensbroek, the Netherlands, approved the standardized protocol according to which the measurements were performed. All measurements were performed by trained research assistants. The research programme included 6 measurement times from the start of active rehabilitation up to 5 years after discharge from clinical rehabilitation. In the current study 3 measurement times were included: working situation before SCI and demographic variables were determined at the start of active rehabilitation, wheelchair capacity and lesion characteristics were determined at discharge from clinical rehabilitation and working situation after SCI was determined 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation.

Variables

Outcome parameters were kept consistent with the previous published study to enable comparison between current results and those obtained for the same cohort one year after discharge (12).

Main outcome measure

Return to work. RTW was determined 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation with the item on having paid work (number of hours/week) from the Utrecht Activities List (16). This questionnaire is a Dutch adaptation of the Craig Handicap Assessment Rating Technique (17). Participants were classified as either having returned to work successfully (RTW group, working 1 h or more per week) or not successfully (non-RTW group). This classification was based on the Dutch situation, in which working 1 h per week in paid employment is considered as successfully returned to work. A self-made questionnaire was used to examine the time between injury and RTW, the kind of job the participants were working in, the assistance to return to work received from the rehabilitation centre or other organizations, and the satisfaction with the assistance received.

Independent variables

Wheelchair capacity. Because wheelchair capacity was determined by the physical capacity and wheelchair skill performance, variables of both were included in the study. The variables were determined at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. As determinants of physical capacity the variables peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) and peak aerobic power output (POpeak) were included. Both parameters were determined during a graded peak wheelchair exercise test, performed with a hand-rim wheelchair on a motor-driven treadmill (18, 19). The drag-force was determined with a drag-test (20). POpeak could be calculated from the individual drag-force and treadmill belt velocity. First, two submaximal exercise blocks of 3 min each (separated by a 2-min rest) were performed with a treadmill inclination of 0 and 0.36o, respectively. After these two blocks, the peak exercise test was started and the inclination was increased by 0.36o every min. Depending on lesion level, the velocity of the treadmill belt was set at 2–4 km/h. The test halted once the participant could no longer keep pace with the velocity of the treadmill. The testing protocol has been described previously by Kilkens et al. (19) and Haisma et al. (18). The VO2peak was defined as the highest value of oxygen uptake recorded during 30 s and expressed by ml/min/kg. The POpeak was defined as the power output at the highest inclination that the participant could maintain for at least 30 s and expressed as Watts.

Wheelchair skill performance was tested on a wheelchair circuit consisting of 8 items: figure-of-8 shape, crossing a doorstep, mounting a platform, 15 m sprint, 3% slope, 6% slope, 3-min wheelchair propulsion and transfer (13, 21). Each item that could be performed adequately and independently was assigned one point, whereas some items (crossing a doorstep, mounting a platform, and transfer) could also score 0.5 point (partially able). Summation of the scored points led to an ability score between zero and 8 points. In addition, the time necessary to perform the figure-of-8 and the 15 m sprint was registered and summed, leading to a performance time score expressed in seconds. Last, a physical strain score, expressed as % heart rate reserve (HRR), was computed from the peak heart rates during 2 of the 8 items (the 3% and 6% slope items), the peak heart rate during the graded peak wheelchair exercise test and the heart rate during rest (22).

Personal and lesion characteristics.Age at the time of injury, gender, level of the lesion, completeness of the lesion, and educational level were included in the present study as possible confounders, since they are assumed to be related to physical capacity (18, 23) and RTW (1, 3, 7, 11, 24–26).

Lesion level and completeness were determined at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and were defined according to the International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI (26). Lesion level was defined as either paraplegia (neurological lesion level below thoracic 1) or tetraplegia (neurological lesion level at or above thoracic 1). Lesion completeness was defined as either motor complete (classifications A and B according to the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS)) or motor incomplete (classifications C and D according to the AIS) (27). Highest completed educational level, classified as low (no or only lower (vocational) education), medium (high school) or high (bachelor/master), was determined at the start of rehabilitation.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the proportion of people who returned to work 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. To detect possible differences at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation between people who dropped out and people who were still participating in the study 5 years after discharge, χ2 tests were performed for the nominal variables gender (1 = woman; 0 = man), lesion level (1 = paraplegia and 0 = tetraplegia) and lesion completeness (1 = motor complete and 0 = motor incomplete) and for the ordinal variable educational level. A Mann-Whitney test was performed for the continuous variables age, VO2peak, POpeak, ability score, performance time and HRR. Additional, similar analyses were performed to determine initial differences between the RTW and non-RTW group (classified 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation). Level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

To answer the second research question, binominal random coefficient analysis (multilevel multiple regression analysis) was used (MlwiN version 1.10; Centre for Multilevel Modelling, Graduate School of Education, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK). The main advantage of this statistical method is that it can account for the hierarchical nature of the data, because the subjects were clustered per rehabilitation centre. The outcome measure in each model was RTW 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation (1 = working; 0 = not working). Separate statistical models for each variable (VO2peak, POpeak, ability score, performance time score and physical strain score) were constructed because of the moderate to strong correlations between these independent variables (Table I). To determine the individual effects of personal and lesion characteristics as possible confounders, each characteristic was evaluated by adding them to each model one by one. If the regression coefficient of the independent variable changed 10% or more (28) when adding age, gender, lesion level or completeness, or education level, this characteristic was considered to be a confounder and was added to the final model, as was previously described by Maldonado & Greenland (29). Because educational level consisted of 3 levels, 2 dummy variables were created with average education as the reference level. If either one or both of these dummy variables was identified as a confounder, both were included in the final model. To investigate which of the independent variables would be associated with RTW when fitted together in one model, a backward regression analysis was performed. The outcome measure was RTW 5 years after discharge from clinical rehabilitation. All WC variables that were individually associated with RTW were added as independent variables. All variables that were confounders in at least one of these separate models were added as confounder.

| Table I. Correlations between the independent variables |

| | Peak oxygen uptake | | Peak aerobic power output | | Ability score | | Performance time score | | Physical strain score |

| r | p | | r | p | | r | p | | r | p | | r | p |

| Peak oxygen uptake | – | – | | 0.784 | 0.000* | | 0.529 | 0.000* | | –0.544 | 0.000* | | –0.575 | 0.000* |

| Peak aerobic power output | 0.784 | 0.000* | | – | – | | 0.654 | 0.000* | | –0.617 | 0.000* | | –0.741 | 0.000* |

| Ability score | 0.529 | 0.000* | | 0.654 | 0.000* | | – | – | | –0.720 | 0.000* | | –0.631 | 0.000* |

| Performance time score | –0.544 | 0.000* | | –0.617 | 0.000* | | –0.720 | 0.000* | | – | – | | 0.674 | 0.000* |

| Physical strain score | –0.575 | 0.000* | | –0.741 | 0.000* | | –0.631 | 0.000* | | 0.674 | 0.000* | | – | – |

| *Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). |

RESULTS

Participant characteristics and the proportion of participants who returned to work

Of the 103 participants, 46 were able to return to work (RTW group; 44.7% of the participants) and 57 were not able to return to work (non-RTW group). Reasons for not working were: being busy taking care of the household and/or children (n = 9), being retired (n = 4), studying in order to get work (n = 6), due to the SCI (n = 16), and other reasons not related to the SCI (n = 5). Seventeen participants did not express an opinion.

Participant characteristics of the 103 participants are shown in Table II. Educational level and ability score were significantly higher in the RTW group compared with the non-RTW group, HRR was significantly lower in the RTW group. The other variables of WC and personal and lesion characteristics did not differ significantly between the RTW and non-RTW group.

| Table II. Participants’ characteristics |

| Working situation 5 years after discharge | Working | | Not working | p-value |

| n | Mean (SD) | | n | Mean (SD) |

| Gender, total | 46 | | 57 | 0.736 |

| Men | 36 | | 43 | |

| Women | 10 | | 14 | |

| Educational level | 43 | | 55 | 0.048* |

| Low | 1 | | 7 | |

| Medium | 29 | | 40 | |

| High | 13 | | 8 | |

| Level of SCI | 40 | | 54 | 0.184 |

| Paraplegia | 29 | | 32 | |

| Tetraplegia | 11 | | 22 | |

| Completeness of the lesion | 39 | | 54 | 0.404 |

| AIS A | 19 | | 29 | |

| AIS B | 6 | | 10 | |

| AIS C | 8 | | 12 | |

| AIS D | 6 | | 3 | |

| Age, years | 46 | 37.4 (11.9) | | 57 | 37.7 (13.3) | 1.000 |

| VO2peak, ml/min/kg | 37 | 18.3 (5.8) | | 34 | 16.4 (6.2) | 0.074 |

| POpeak, W | 37 | 54.4 (23.9) | | 35 | 45.6 (24.7) | 0.108 |

| Ability score, points | 39 | 7.3 (1.4) | | 41 | 6.1 (2.5) | 0.006* |

| Performance time, s | 39 | 18.3 (7.3) | | 42 | 22.8 (12.8) | 0.065 |

| Physical strain, % HRR | 34 | 29.5 (17.8) | | 33 | 38.7 (20.7) | 0.049* |

| *Statistically significant different at p ≤ 0.05. Number of participants vary between the analyses because not all participants were able to perform all tests and some values were missing. VO2peak: peak oxygen uptake; POpeak: peak aerobic power output; SCI: spinal cord injury; AIS: American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; SD: standard deviation; HRR: heart rate reserve. |

Working situation

Most of the participants (n = 70) who were included in the study were working full time (≥ 36 h/week) before injury. The median number of hours participants worked was 40.0 (P25: 36.0; P75: 55.0). Five years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation the median number of hours was 20.0 (P25: 15.8; P75: 32.8): 10 people were working full-time and 36 people part-time (Table III).

| Table III. Hours of working before spinal cord injury (SCI) and 5 years after discharge of clinical rehabilitation |

| 5 years after discharge | Before SCI |

| 1–18 h n | 18–36 h n | > 36 h n |

| Not working | 8 | 15 | 34 |

| Working | | | |

| 1–18 h | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| 18–36 h | 1 | 4 | 16 |

| > 36 h | 0 | 0 | 10 |

Before SCI there were 30 white-collar workers (performing mostly non-manual labour) and 73 blue-collar workers (performing mostly manual labour). Of the 46 people working after SCI 38 people were white-collar workers (of whom 20 previously also had a white-collar job, 63.2% had a paraplegia and 52.6% had a complete lesion) and 8 were blue-collar workers (of which 6 people previously had a blue-collar job, 62.5% had a paraplegia and 62.5% had a complete lesion). In conclusion, 73.3% of the (previously) white-collar workers and 32.9% of the (previously) blue-collar workers returned to work.

For the participants who returned to work, median time from injury to RTW was 12 months (range: 3–72 months). Twenty-one participants returned within 1 year after injury, 9 between 1 and 2 years, 6 between 2 and 3 years, 1 between 4 and 5 years and 4 participants between 5 and 6 years after SCI. The time from injury to RTW was unknown for 5 participants.

The question as to whether assistance to return to work was received from the rehabilitation centre was answered by 95 out of 107 participants: 14 participants received assistance, but 12 of these participants reported that this assistance was insufficient. The remaining 81 participants reported that they received no assistance from the rehabilitation centre. Twelve of them reported being satisfied about that, while 45 participants reported that they missed the assistance and 24 participants did not express an opinion. The question as to whether assistance to return to work was received from any other organization was answered by 93 out of 107 participants: 32 participants received assistance, but only 8 of these participants reported that this assistance was sufficient, 23 participants reported that this assistance was insufficient and 1 participant did not express an opinion. The remaining 61 participants reported that they received no assistance from any other organization. Eight of them reported being satisfied with this situation, while 34 participants reported that they missed the assistance and 19 participants did not express an opinion.

Wheelchair capacity

Table IV shows the included variables and the outcomes of the constructed models.

| Table IV. Results of the multilevel multiple regression analyses with return to work 5 years after discharge of inpatient rehabilitation as outcome measure |

| Variables included in the analysis | Wheelchair capacity variable |

| Peak oxygen uptake, ml/min/kg | Peak aerobic power output, 10 W | Ability score, points | Performance time, s | Physical strain score, 10% HRR |

| β (SE) | p | OR | β (SE) | p | OR | β (SE) | p | OR | β (SE) | p | OR | β (SE) | p | OR |

| Constant | –0.457 (1.085) | | | –0.862 (0.846) | | | –2.900 (1.421) | | | 3.504 (1.451) | | | 2.123 (1.092) | | |

| Wheelchair capacity variable | 0.095 (0.055) | 0.084 | 1.10 | 0.325 (0.148) | 0.028* | 1.38 | 0.488 (0.213) | 0.022* | 1.63 | –0.124 (0.053) | 0.019* | 0.88 | –0.347 (0.167) | 0.038* | 0.71 |

| Age | n.e. | | | n.e. | | | n.e. | | | n.e. | | | n.e. | | |

| Gender | n.e. | | | 0.991 (0.697) | 0.156 | 2.69 | n.e. | | | n.e. | | | n.e. | | |

| Lesion level | –0.699 (0.770) | 0.364 | 0.50 | –0.965 (0.750) | 0.198 | 0.38 | –0.443 (0.659) | 0.501 | 0.64 | –0.912 (0.723) | 0.207 | 0.40 | –0.730 (0.762) | 0.338 | 0.48 |

| Lesion completeness | –1.142 (0.646) | 0.077 | 0.32 | –0.337 (0.575) | 0.558 | 0.71 | –0.408 (0.520) | 0.433 | 0.66 | –0.795 (0.544) | 0.144 | 0.45 | –0.578 (0.571) | 0.311 | 0.56 |

| Education (low–medium) | –1.800 (1.201) | 0.134 | 0.17 | n.e. | | | n.e. | | | n.e. | | | n.e. | | |

| Education (medium–high) | 1.175 (0.673) | 0.081 | 3.24 | n.e. | | | n.e. | | | n.e. | | | n.e. | | |

| *Statistically significant different at p ≤ 0.05. OR: odds ratio; 10% HRR: per 10% heart rate reserve; n.e.: not entered; SE: standard error. |

Physical capacity

Lesion level, lesion completeness and educational level were confounders in the relationship between VO2peak and RTW. Gender, lesion level and lesion completeness were confounders in the relationship between POpeak and RTW. After correction for these confounders VO2peak was not significantly associated with RTW, while POpeak was. Persons with a 10 Watt higher POpeak were 1.38 times more likely to return to work.

Wheelchair skill performance

Lesion level and lesion completeness were confounders in the relationships between the variables of wheelchair skill performance and RTW. After correction for the confounders, ability score, performance time and HRR were significantly associated with RTW. Persons with a 1-point higher ability score were 1.63 times more likely to RTW. An increase, or worsening, of 1 s on the performance time gave an odds ratio of 0.88, so persons with lower, or better, performance time scores were more likely to RTW. An increase, or worsening, of 10% on the physical strain score gave an odds ratio of 0.71, so persons with lower, or better, physical strain scores were more likely to RTW.

Multivariate analysis

POpeak, ability score, performance time and physical strain score were associated with RTW and were therefore included as independent variables in the backward regression analysis. Gender, lesion level and lesion completeness were added as confounders. Only the independent variable performance time remained in the final model of this analysis.

DISCUSSION

The first aim of the current study was to investigate the proportion of people who returned to paid work 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and to describe their working situation. Of the participants who had paid work before SCI, 44.7% returned to work within 5 years after inpatient rehabilitation. Some of these participants seemed to return to the same working situation as before SCI, but for most participants their working situation changed: they were working part-time instead of full-time after SCI or returned to less physically demanding jobs (they changed from a blue-collar job to a white-collar job). This last finding is similar to the results of other studies (1, 30, 31). In the current study RTW was determined 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. At that moment mean time since injury was approximately 6.5 years (mean 2,383 days). The RTW rate of 44.7% found in this study is high compared with the RTW rates of other studies with a comparable time since injury. Tomassen et al. (1) reported a similar 48% RTW 4–6 years after injury, but after more than 6 years post-injury they reported 31% RTW. Tomassen et al. (1) used the same definition of having paid employment as in the current study. Meade et al. (9) reported 18.7% RTW after 5 years and 22% after 10 years. In the study of Franceschini et al. (4) 29.5% returned to work after 6 years (mean), of whom 35.8% were not paid workers. Only Schönherr et al. (30, 32) reported a higher % RTW: 67% 7 years (mean) after injury. The differences in RTW between the studies could be due to differences in the definition of RTW or to differences in culture and legislation. In addition, the inclusion criteria could have influenced the outcome. In the current study it was decided to include participants only if they were working before injury and if the working situation 5 years after discharge from clinical rehabilitation was known. Except for the study of Tomassen et al. (1), in the other studies not all the participants were working before injury. As a result, the percentage RTW of the current study could be relatively high compared with other studies. Comparing the RTW rate with that of our earlier study on RTW 1 year after discharge, the RTW rate increased from 33% to 44.7%. Most participants who were working one year after discharge were also working 5 years after discharge. These results indicate that RTW increases over time and that most participants were able to keep working over time. This increase of RTW over time was also confirmed in earlier studies (5, 6, 33, 34). A possible explanation for this increase can be that people were still receiving outpatient rehabilitation one year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation: they needed to be at a stable level of functioning first. Moreover, it can be expected that people needed time to get used to their new life at home (1). Little time is left for work then. Five years after discharge, the rehabilitation process was finished for most people. In addition, 5 years after discharge people have had time to re-educate themselves if this was needed (33). The process of, and time to, RTW might be improved by better assistance, given by the rehabilitation centre or any other organization (6, 26). Most people reported that they have missed some assistance during their process of RTW or that the assistance provided is not sufficient.

Wheelchair capacity

From the results of the study it can be concluded that RTW 5 years after discharge is positively associated with WC at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. People who scored better on POpeak, ability score, performance time and physical strain score were more likely to return to work. In the backward regression analysis, all independent variables except for performance time were removed from the model, probably due to the moderate to strong correlations between the independent variables. The results of the current study are comparable to results of our study performed 1 year after discharge (12) in which the POpeak, ability score and performance time score were found to be associated with RTW. In contrast, HRR was associated with RTW 5 years after discharge, although it was not 1 year after discharge. Possibly this is a result of the more equal distribution of the RTW and non-RTW group 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. The association found in this study does not prove causality, but it nevertheless suggests that the functional benefits of wheelchair training might translate into better RTW. Therefore, it is recommended to train WC during rehabilitation. Fortunately the training of WC is an important functional activity in most (Dutch) SCI rehabilitation programmes, dedicated to improving mobility and functional independency. In the current study, mean duration of inpatient rehabilitation was 207 (standard deviation 127) days. Because all large Dutch rehabilitation centres specialized in SCI rehabilitation participated, it can be expected that the mean duration of inpatient rehabilitation is representative for the Netherlands. In case the rehabilitation period is shorter in another rehabilitation setting, possibilities for training WC during rehabilitation are decreased. In that case, it is recommended to train wheelchair capacity after rehabilitation if possible.

Study limitations

In the Dutch Research Project, people were not included if they were expected not to remain wheelchair dependent. Therefore, the participants of the current study might experience more disabling results of their SCI compared with the participants of other studies. On the other hand, people were not included if they had major complications or were not working before injury. As a result, the RTW rate of 44.7% may be an underestimation or an overestimation.

The focus of the current study was on the relationship between WC and RTW. Other aspects of functioning, such as complications, social and psychological factors, could also influence WC (35), RTW and the relationship between WC and RTW. However, to limit the scope of this study it was decided not to include these variables. It would be interesting to include these variables in future studies to investigate the combined effect of all aspects of functioning and co-morbidities.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in the current study 44.7% of the included participants returned to paid work within 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. The percentage of RTW is higher than RTW 1 year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation in the same study sample. The reason for this may be because people had time to get used to their new life and due to re-education. RTW 5 years after discharge is related to WC at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. To improve the likelihood of return to work, it is recommended to provide training in WC during rehabilitation. Because most participants reported that they did not receive (sufficient) assistance, it is recommended to improve vocational counselling and other support targeted at RTW. Rehabilitation centres can play an important role in this process due to their high level of knowledge of SCI.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the research assistants for collecting all the data and the following participating Dutch rehabilitation centres: Rehabilitation Center De Hoogstraat (Utrecht), Rehabilitation Center Amsterdam (Amsterdam), Rehabilitation Center Het Roessingh (Enschede), Adelante (Hoensbroek), Sint Maartenskliniek (Nijmegen), Rehabilitation Center Beatrixoord (Haren), Rehabilitation Center Heliomare (Wijk aan Zee), and Rijndam Rehabilitation Center (Rotterdam).

REFERENCES